SORBUS spotlight: Trump

It was not too long ago that “political risk”, the notion that an election result or a political decision could seriously impact upon asset market returns, was primarily the concern of investors in emerging markets. When it came to the advanced economies, central bankers seemed to matter a lot more than politicians. The Eurozone crisis of the early 2010s, the Brexit referendum of 2016 and the entry of Donald Trump into American politics have changed all of that.

Ahead of Donald Trump’s victory, some speculators moved into so-called “Trump trades”, buying the dollar, crypto currencies and US equities, which have so far mostly paid off. So what does the election of Trump 2.0 mean for the US and global economies? The gap between manifesto and the actual policies pursued by any politician in office can be large. With Trump the uncertainty factor, as in 2017-2021, is even higher. But some broad outlines are clear.

The logic behind the Trump Trade was that a second Trump term would be good for US equities, bad but not terrible for US bonds and positive for the dollar. To unpack those assumptions it is worth looking in turn at the likely impact of tariffs and Trump’s wider domestic agenda.

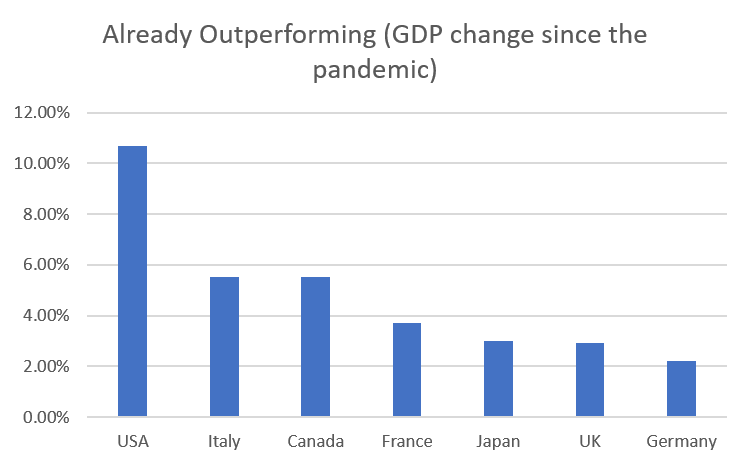

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, OECD (data as at: 19/11/2024)

The best starting point is to remember that US economic performance since the pandemic has been much stronger than that experienced in other rich countries. A few factors sit behind that: the fiscal and monetary response was much stronger, the US – a continental market – was less badly hit by the disruption in global trade and America, post the shale gas revolution, was far less exposed to the global energy price shock of 2022-23.

In the short term at least, the Trump administration is likely to turbo-charge this divergence.

Trump’s signature policy is raising tariffs to keep out foreign imports and, as he sees it, protect American jobs. This time around Mr Trump is promising tariffs, or import taxes, of 10-20% on all imported goods with some sectors and countries possibly targeted for higher levies. It remains unclear whether this should be seen as the opening gambit for trade talks which might be negotiated down or not. The timing is also up for debate, with some Trump advisors suggesting they could start at a low level and be slowly ramped up over 2-4 years and others suggesting they would come in at high levels from early on in the new administration.

The experience of the first Trump term offers some clues as to the likely economic impacts within the United States. Of course the interest rate and inflation environment was rather different in the late 2010s so comparisons need to be taken with more than the usual pinch of salt.

In general though tariffs tend to drive the price of goods subjected to them up. A 10% levy on, say cement imported from Mexico, will increase the price of Mexican cement in the United States. But the pass-for from tariff rates to final prices is rarely exactly one for one. It may be, for example, that Mexican cement exporters absorb some of the blow through marking down prices to maintain market share. Much depends on the structure of the underlying market and the existence of domestic supplies.

There can be little doubt that the sweeping increases in tariffs being proposed by Mr Trump would increase the rate of inflation domestically, estimates vary from as little as the annual rate of price changes rising by 0.4 percentage points to as much as 1.5 percentage points. Domestic employment would likely be higher in the industries now subject to protection but at the cost of higher prices for firms and households in general.

Such tariffs would of course also impact the economies of the US’s trading partners.

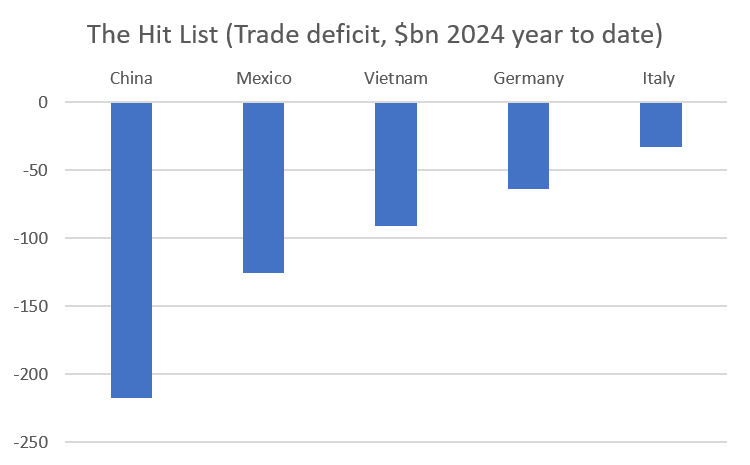

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, US Bureau of Economic Analysis (data as at: 19/11/2024)

The chart above shows those first in the firing line. A few things are worth keeping in mind here. Firstly, tariffs are likely to shrink rather than eliminate such bilateral trade deficits. And secondly, many of the countries impacted are likely to respond with their own tariff regimes – hitting US exports.

Most importantly though, the US bilateral trade deficit figures above do not take into account the size of the trading partner’s wider economy. China’s, for example, total exports to the United States represent just 3% of it’s GDP. A fall of, say, one third would be painful knocking the already depressed GDP growth rates down by 1% but manageable. For Mexico though, exports to its northern neighbour represent almost one third of GDP. A one third contraction there would mean a deep and painful recession.

If implemented in full Mr Trump’s tariffs might reduce Chinese GDP by around 1%, European GDP by around 0.8%-1% and that of smaller but important trade partners such as Mexico and Vietnam by considerably more.

What then of the rest of Mr Trump’s domestic agenda. The centre pieces here are large cuts to corporation tax (by extending tax cuts made in 2017 and due to expire in 2025), cuts to personal taxation and sweeping deregulation.

In the short run at least, this should all be positive for growth. Although like the tariff measures, such policies would also add to inflationary pressure by fuelling demand. Mr Trump’s talk of the mass deportation of illegal migrants would also further tighten the jobs market and likely push wage costs and price pressures higher still.

In other words, all of these (non-tariff) policies will likely increase GDP growth in the short to medium term but come at the cost of faster price growth. All things being equal, to use the beloved phrase of economics, that means that the Fed would be forced to hold rates higher for longer than would otherwise by the case.

This is the macroeconomics behind the Trump Trade logic that has gripped markets in recent weeks. Faster US growth and lower tax rates are good for profits pushing US equities higher whilst higher for longer rates are bearish for bonds but positive for the dollar.

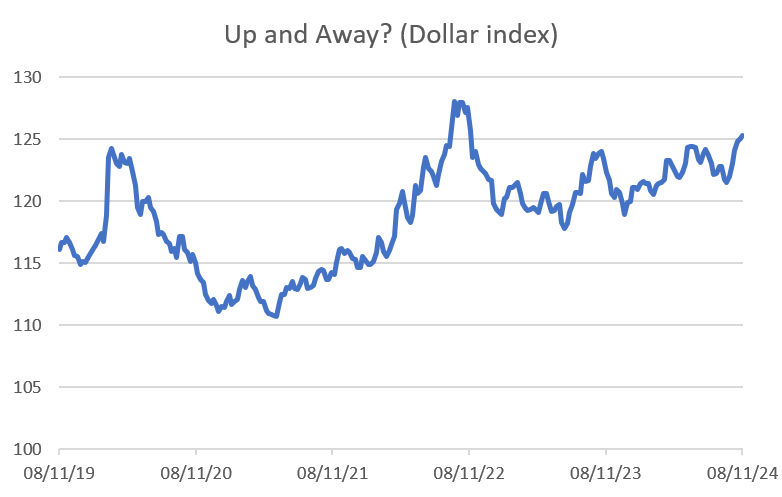

In a world where US growth is supercharged and tariffs are a drag on many other countries, then one might expect the rate differential between the United States and the rest of the world to widen making holding dollars more attractive: hence the recent climb in the dollar.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED, data as at: 19/11/2024)

Analysts expect this to continue. Depending on the exact policy mix and its timing, a further rise in the value of the greenback seems eminently possible.

The impact of a rising dollar will be felt well outside of America’s borders. The dollar sits at the heart of both the global financial system and global trade and a rising dollar has long been associated with a weaker global economic outlook.

The IMF reckons that a 10% rise in the value of the dollar decreases economic output in emerging economies by 1.9 percentage points after one year and that the impact lingers for around two and half years. Rich countries are less directly affected, but still see their output cut by 0.6 percentage points with the fall lasting for a year or so.

A rising dollar depresses global activity via two mechanisms. Firstly, through trade. More than 40% of global trade, most of it not involving America, is invoiced in dollars. A stronger dollar raises the real costs for importers and lowers demand, reducing overall trade volumes. Trade volumes across much of Asia and Latin America are, as result, more tied to the value of the dollar than local currencies. One academic study found that a 1% rise in the value of the dollar against all currencies predicts a 0.6% decline in trade between countries in the rest of the world, even after controlling for other factors.

Just as important as the trade impacts of a rising American currency is the financial feedback. For countries and firms that have borrowed in dollars but lack sources of dollar revenue, a rising dollar increases the effective size of their debt burden and interest costs. More generally, higher American interest rates and a rising currency make investing on other markets less attractive. As the dollar rises other economies, especially emerging markets, are usually subjected to capital outflows tightening their domestic financial conditions.

Mr Trump has pledged to put America First. His economic agenda certainly points in that direction with the cumulative impact likely to be a pick up in US growth coupled with a tougher environment in Europe, China and emerging markets. Quite how long the period of US outperformance would last though is tricky to say. At some point higher rates and inflation will begin to bite. It may be that the short run sugar rush is followed by a longer hang-over.

|

What we are watching US PCE Inflation, 27th November: The Fed’s preferred gauge of inflation has stubbornly refused to fall as hoped in recent months. After 0.75% of cuts in two meetings the Fed was already signalling that it would cease further easing for a while, even before the Presidential election. EU Confidence, 28th November: Donald Trump will not take office until January but his victory will likely depress business confidence well before that amongst exporter-heavy European firms. |