SORBUS spotlight: The economy in 2024. Five key points.

2023 turned out to be a lot better than expected. A year ago the consensus view was that high energy prices would push the British and European economies into recession and the chances of a similar downturn in the United States were closely balanced.

In reality, energy prices fell faster than expected whilst government support for both households and firms globally was more robust than expected. The result was a year of weak growth but growth nonetheless. Going into 2024 expectations are somewhat higher than 12 months ago, but one would be hard pressed to call them high.

At the global level, five key trends are worth noting.

The pandemic is finally over.

2023 was the year, economically speaking at least, when the global pandemic could be said to have ended.

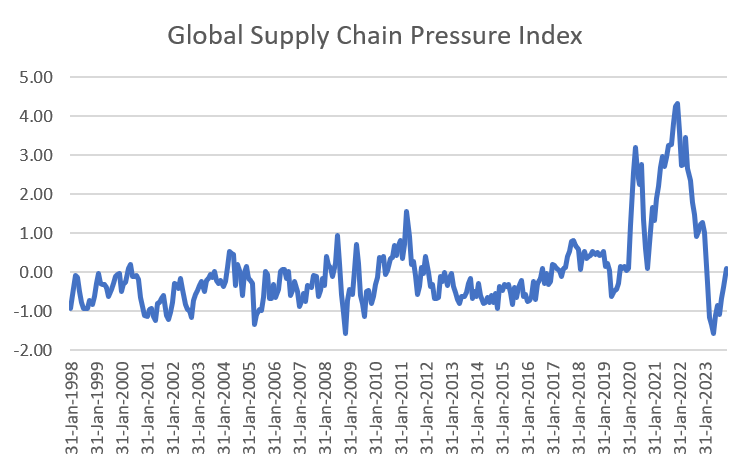

source: SORBUS PARTNER, New York Fed (data as at: 13/12/2023)

The global economy is a complex and complicated machine with many interlocking parts. It is almost impossible to summarise it in one chart. But if pushed, the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s index of global supply chain pressure is not a bad option.

The economic history of the past few years is clearly visible. The initial shock to global supply chains as the pandemic hit in 2020 was much larger than anything seen in the previous two decades – it dwarfed both the Japanese earthquakes of 2010 and the Eurozone crisis of 2012-15 in magnitude.

Pressure first ramped up as China, the centre of many global value chains, locked down in early 2020 and put large pressure on global supply but dissipated as the advanced economies locked themselves down too lowering global economic demand.

In 2021 as economies reopened and vaccines were rolled out, the measure of pressure soared to new highs. Turning global demand on and off, economists learned, could be done by government decree but supply was not so simple. The rebound in global demand in 2021 and early 2022 pushed many supply chains to breaking point, a problem exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and China’s continuing rolling shutdowns.

The result was a surge in global goods prices that triggered a take-off in global inflation. But, slowly and surely, over the past 18 or so months the pressure has fallen away. It may have taken longer than policymakers hoped but the New York Fed’s measure of supply chain pressures has finally returned to more normal levels.

The pandemic has reshaped global economic activity – and in particular the persistence of working from home is likely to change the nature of many cities – but the direct impacts on global supply seem to finally have unwound.

Growth is present, but weak.

Any sort of growth is preferable to a contraction but the levels of growth currently being ‘enjoyed’ is historically weak.

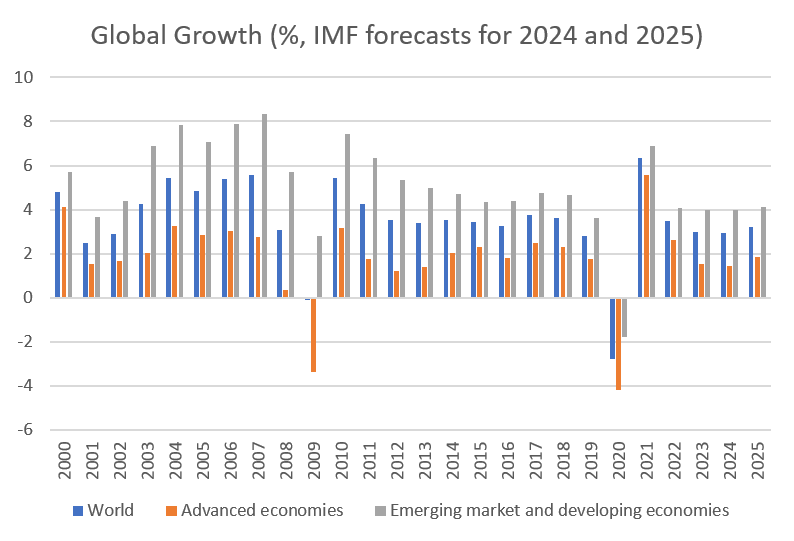

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023

The IMF reckon that the world economy grew by just 3% in 2023 and looks set for a similar out turn in 2024. Global growth averaged 3.8% in the twenty years before 2020 and the 3% growth of 2023 and 2024 represent the weakest performance (outside of 2009 and 2020) seen in decades.

For the advanced economies the picture is even grimmer. They collectively expanded by just 1.5% in 2023 and are expected to grow at a marginally slower pace next year.

The global economy, as a whole, is around two percentage points smaller than it was expected to be by the IMF by this time ahead of the pandemic. With no real evidence of any above-trend catch-up growth occurring, it would appear that that 2% has been lost and represents the long-term scarring impact of the pandemic.

Inflation has probably peaked. But it remains high.

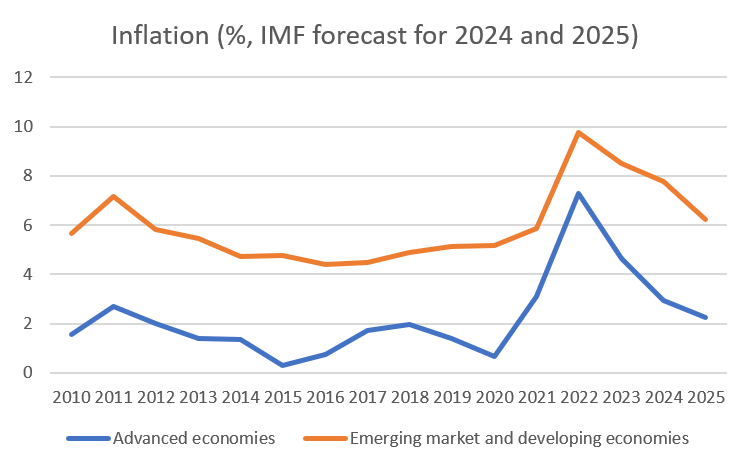

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023

Global inflation surged in 2021 and 2022. The supply chain pressures resulting from and revealed by the pandemic pushed up goods prices, the energy price shocks of 2021 and 2022 added to the misery and tight jobs markets sent wage growth heading northwards. Central banks left stimulatory policies in place for too long.

The good news is that inflation looks to have peaked. But whilst the IMF expects it to continue falling in 2024 and into 2025 they now see it settling at a higher level than before the pandemic.

Advanced economy inflation averaged just 1.5% in the 2010s compared to a forecast 3% in 2024 and 2.2% in 2025. After a double-digit peak (when measured month by month rather than – as this chart does – averaging change over the entire year), 3% might feel like a blessed relief for many firms and households. But given that most central banks target 2%, it remains higher than desired by policymakers.

One of the big questions for the mid-2020s is: at what level will inflation eventually settle? The decade of ultra-low, and persistently below central banks’ targets, inflation of the 2010s is over – but is the world returning to the steady and at target inflation of the 1990s and early 2000s or a higher and more volatile era like that which came before?

Welcome to Table Mountain

Whilst the fall in inflation over the course of 2023 has been welcomed, the mechanism through which the fall came was less pleasant for firms and households.

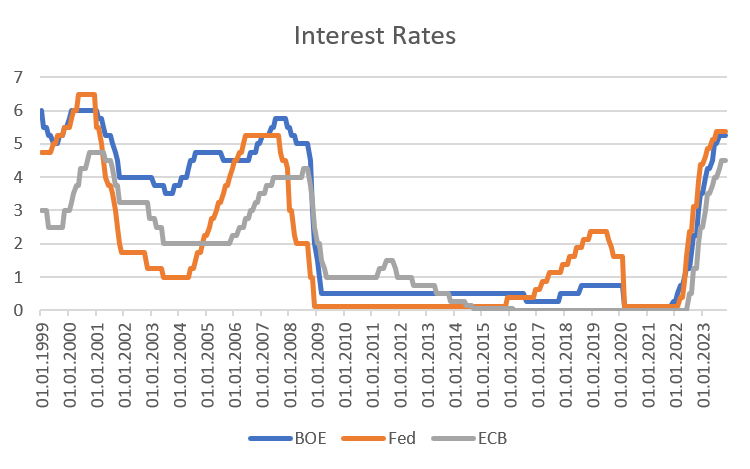

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Bank of International Settlements (BIS) (data as at: 13/12/2023)

Advanced economy central banks have tightened policy sharply since the end of 2021. The pace of rate rises has been the fastest since the 1980s and much of the pain is yet to be felt.

The typical lag between a rate rise being enacted and its full effect being felt is 18 to 24 months. One member of the Bank of England’s rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee recently argued that only 25% of the tightening has been fully absorbed by the real economy so far. That number is far from precise but is likely in the right sort of ballpark. 133,000 fixed rate mortgages are due to expire every month between now and December 2024 in the UK with the typical household likely to see their monthly bills rise by £288 after a reset.

Markets now believe that rate rises have likely peaked but central bankers are keen to argue that whilst further tightening may not be needed, the job of beating inflation is not yet complete. Huw Pill, the Bank of England’s chief economist, reckons that the chart of rates might well resemble Table Mountain – a steep path of hikes, followed by a long plateau.

After a decade of arguing that rates would be ‘lower, for longer’ central bankers are now keen to emphasise that they will be ‘higher, for longer’ and that both firms and households need to get used to the idea of rates around 5% for the medium term. 2024 will see many parts of the economy – and in particular overleveraged sectors – struggling to adjust to this reality.

Markets need more convincing

The big problem facing central banks globally is that markets do not seem to fully believe them. For all the hawkish talk of vigilance on inflation, mountaineering analogies and the fact that the battle is not yet won, markets in general expect rate cuts in 2024.

That is a problem for policymakers. The very fact that easing is expected blunts the impact of rates.

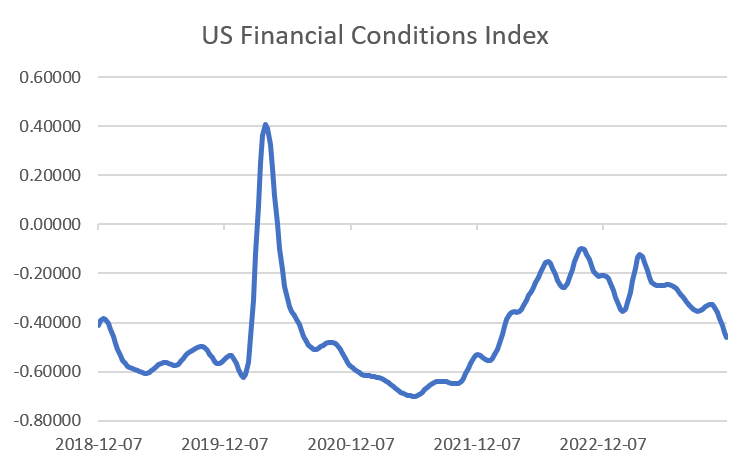

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (13/12/2023)

The best way to look at this is to glance at the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank’s index of financial conditions in the United States.

A lower reading means financial conditions for firms are easier – loans are easier to come by, credit conditions are relaxed, refinancing is more available – whilst higher levels indicate tighter credit conditions and less available finance.

Over the course of 2023 financial conditions have eased despite the Fed continuing to tighten in the first half of the year and staying put in the second.

That mostly reflects expectations of future cuts to come – the very belief that rates will be cut in the near-ish term has a direct impact on the economy now.

Over the next few months central bankers are likely to up their hawkish talk and try to guide market expectations higher to tighten credit conditions in the short term. Whether that will work or not will be one of the key questions facing the global economy in early 2024. If it does not then further rate hikes may be needed to bring inflation back to target.

|

What we are watching US Quits, 4th January – The US jobs market is still too tight for the Fed’s liking. As previously noted in Spotlight, the US monetary tightening so far has managed to cool the jobs market mostly through a fall in hiring and posted vacancies rather than through redundancies and rising unemployment. That may not last much longer. The best early sign of how the jobs market is actually performing is the monthly quit rate – the percentage of workers voluntarily leaving their employer. A high quit rate tends to signal a strong jobs market as workers are confident of other opportunities. |