SORBUS spotlight: the central bank sweet spot

It might not feel like it but the global economy, at least from the point of view of Western central bankers, is currently in something of a sweet spot. Rates have been aggressively hiked, the battle against inflation appears to be slowly being won (or has at least checked its advance) and yet the usual economic pain – in terms of job losses – is not yet being felt to anything like the extent that is typical. How long can this last?

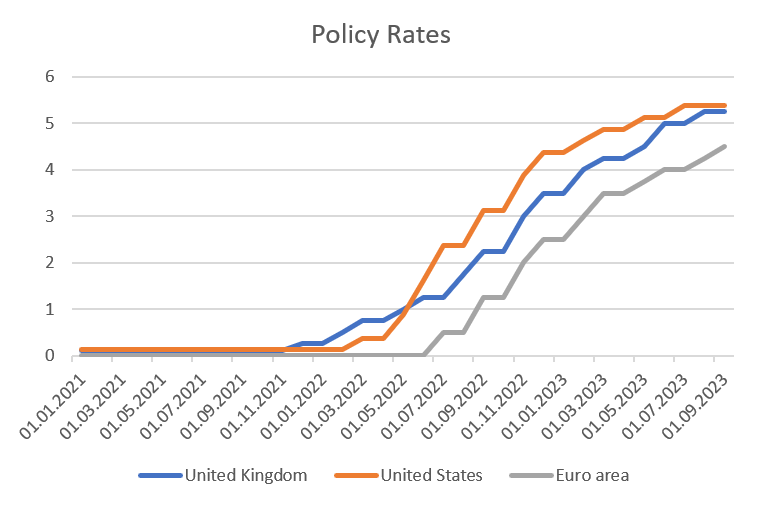

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Bank of International Settlements (data as at: 30/10/2023)

After more than a decade of ultra-low interest rates the inflationary spike of 2021-2022 prompted central bankers into returning their policy rates to levels that were once considered normal.

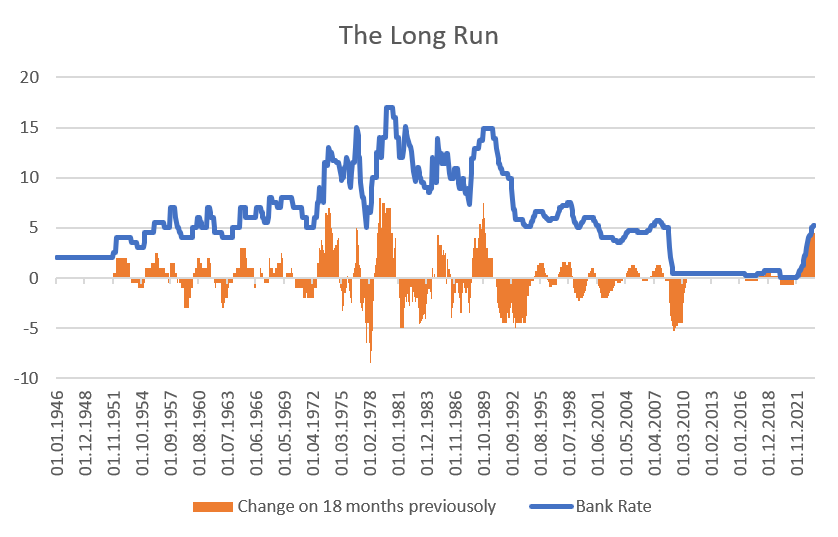

To get a sense of the magnitude of the recent months the chart below looks at the Bank of England’s base rate back to 1945 and, as well as the level of rates, shows the change over 18 months.

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Bank of International Settlements (data as at: 30/10/2023)

The tightening since 2021 dwarfs the hiking cycles of the 2000s and 1990s and is the most aggressive tightening cycle – in terms of both size and pace – seen since the early 1990s.

The Bank is far from atypical here and most economists would argue that a simple look at rates understates the extent of the turnaround in policy. Quantitative easing, the electronic creation of new money to purchase government bonds by central banks, was in use from 2008 until 2021. Whilst the exact impact remains a topic of debate, there is little doubt that it represented an easing of monetary conditions beyond the usual lever of cutting rates. Since 2021 the process has gone into reverse with central banks reducing the size of their balance sheets. Such non-base-rate-related unconventional monetary policy is not captured by a simple look at policy rates. It is plausible to argue that the switch from balance sheet expansion to contraction is the equivalent of another two or even three percentage points of rate moves. Adding such an impact onto the chart above would make the policy tightening since 2021 at least as large as that experienced in the 1970s.

In other words the sudden about turn in monetary policy over the past two years is very possibly at least equal to the biggest swings in policy rates experienced by the advanced economies since the end of the Second World War.

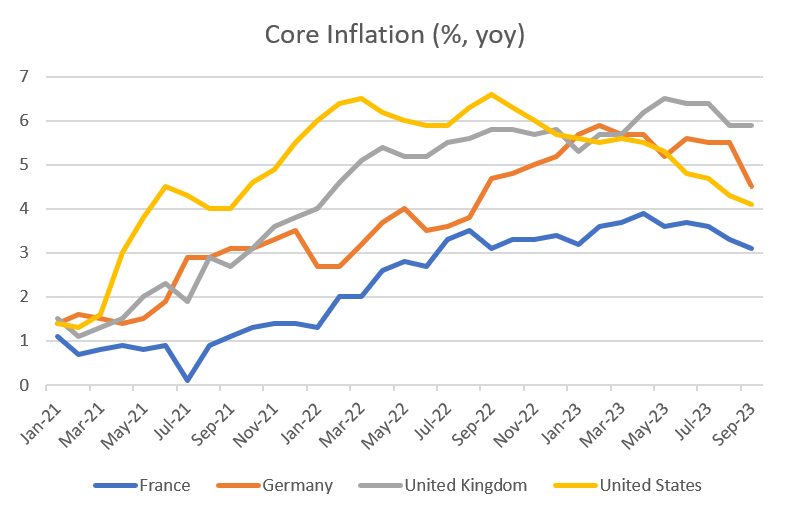

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, OECD (data as at: 30/10/2023)

Core inflation, excluding food and energy, is most central bankers preferred measure of price pressures. Whilst excluding items which are just about as unavoidable to purchase as any imaginable might seem perverse to consumers, the measure has some advantages for policymakers. For a start energy and food prices tend to be the most volatile components of inflation – so excluding them gives a cleaner picture of the underlying inflationary trend. More importantly though energy and food prices tend to be driven by global supply and demand and reflect global rather than domestic conditions. Given there is little central bankers can do to influence or control such factors they generally prefer to set policy in response to domestic conditions and “look through” imported price shocks.

Core inflation, in theory, gives a better measure of domestic price pressures and is more reflective of conditions in national labour markets. It tends to move in line with local services price inflation and wage levels.

In the US the Federal Reserve has been much cheered by core inflation dropping from around 6.5% last Autumn to just over 4% currently. European policymakers too can take heart from recent falls. In Britain core inflation is proving more stubborn but has at least stopped accelerating.

There is then some evidence that the rate rises of the past two years are working as intended in terms of reducing inflation. But what makes the current moment a sweet spot for central banks is that those rate rises do not appear to be doing the damage to jobs markets that they usually do.

The last two global business cycles were deeply unusual. In 2020 a global pandemic and government dictates ordering economic activity to cease to protect public health pushed economies into recession. In 2008/09 a sudden global banking crisis caused lending to plummet and output to drop.

By contrast previous cycles, as seen time and time again from the 1950s until the early 2000s tended to follow a different and familiar pattern. Eventually economies would begin to overheat as their demand grew faster than supply could cope with. Jobs markets became tight pushing up wages and bottlenecks began to appear in production chains. Inflation would drift upwards and central banks would respond by pushing up interest rates to cool demand and slow growth. Eventually higher rates would begin to bite and households would cut back on spending whilst firms paused hiring and investment plans. The end result was usually a recession engineered by tighter monetary policy that pushed up employment and drove up bankruptcies but also materially reduced inflation. Central banks could then start cutting rates, businesses would begin to grow again and household spending would start to recover. The cycle would begin again.

The short version is that in a ‘normal’ policy cycle central banks push up rates until something breaks down. And it is that breakage which helps cool inflation.

This time around, there is so far at least very little evidence that the largest tightening cycle in decades is causing the usual kinds of pain in the jobs market.

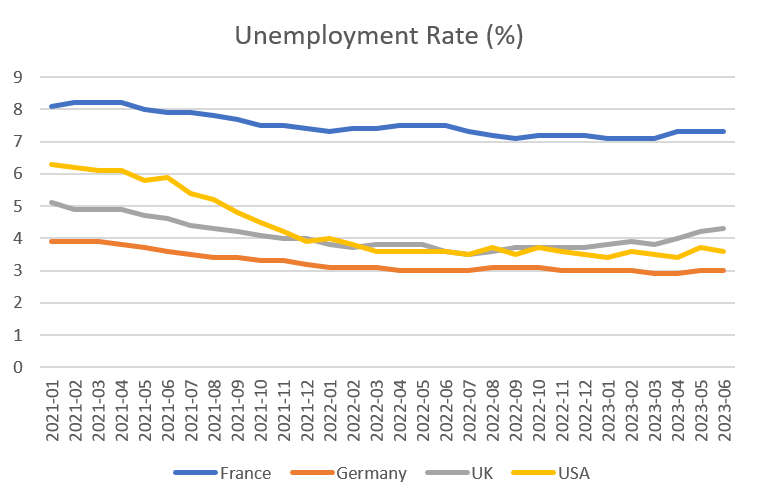

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, OECD (data as at: 30/10/2023)

In fact the level of unemployment across the major economies is spectacularly low given the changes in economic policy.

Just a year ago central bankers were convinced that increasing jobless rolls would be the cost of inflation reduction. The very fact that central bankers are able to make such ‘tough calls’ as putting people out of work in order to maintain price stability is the central argument for central bank independence. As they are not beholden to the voters they are seen as ‘credible’ players able to do what is necessary. In theory, the very fact that they have such credibility should help keep inflation stable – if wage setters believe that the central bank will do whatever it takes to keep prices stable then they should, hopefully, set wages accordingly.

This time around though the world seems to be experiencing an immaculate monetary tightening. Price pressures are falling without the usual trade-off of rising unemployment.

How has this been achieved? The answer, so far, seems to be found in job vacancies. Firms so far, in the United States and Europe at least, have reacted to a change in conditions by cancelling hiring plans rather than laying off staff. Whilst redundancies have only gradually crept up, advertised job vacancies have plummeted. Even in Britain, which is something of an outlier, the number of vacancies has fallen from 1.3 million last spring to under 1 million this month.

That may reflect the situation of a labour shortage firms found themselves struggling with in 2020-2022 – perhaps having experienced the harsh impacts of not being able to find enough workers, firms are now keen to hang on to those they have even if demand conditions are weak.

But labour hoarding cannot last forever.

Inflation may have moderated but remains uncomfortably high. The fear now is that the ‘easy bit’ is done. Whilst the top of the hiking cycle may well have been reached, the full impact of what has changed over the last 18 or so months is yet to be felt. Monetary policy, as central bankers often note, works on a long and variable lag. For most firms and households, the effects of a change in rates are not felt instantaneously. It takes time for fixed rate loans to expire and be refinanced. Usually the lag between a change in a policy rate being made and the full economic fallout being experienced is something like 18-24 months. In other words, given most tightening cycles only appear to have peaked in the past few months it could well be another year to 18 months before central bankers can really judge how much collateral damage there has been in the war against inflation.

Firms may be hoarding labour and content to reduce hiring plans now but whether they will still be happy to do so in a year’s time remains debatable. The base case should be that unemployment will begin to rise across the advanced economies towards the end of this year and into next. That will add to pressure on household spending and growth. The sweet spot will not last forever.

|

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING 10th November, British GDP: Britain looks to have avoided a recession so far but one is still possible in the coming quarters. Growth for the third quarter looks set to be sluggish but still positive. Whether that will continue into the final quarter remains unclear. 21st November, PMI Day: The global Purchasing manager indices (compiled by a survey of purchasing managers at major firms) is the most useful timely global snapshot on conditions at firms. The thing to watch for is hiring and firing plans. |