SORBUS spotlight: Change in service sector activity 2020-22

The pandemic ushered in great economic changes. It helped rekindle global inflation after two decades of tepid price rises. It pushed up the level of government debt across all advanced economies. It caused many firms to rethink the nature of their supply chains and to prioritise resilience of efficiency, possibly giving a further knock to cross-border trade and globalisation. All of these, in their own ways, may prove to be negative for global prosperity. Until recently the one upside of a global pandemic and two years of on-again off-again lockdowns appeared to be the rise of hybrid working. Now though even the supposed upsides of this megatrend are being questioned. But regardless of the pros and cons of more working from home, it is slowly but surely reshaping the economic landscape and changing long-standing patterns of economic geography.

At the time the sudden surge in home working as employees who could work from home were encouraged to do so in the Spring of 2020 appeared to run remarkably smoothly. Very quickly the apparent upsides were talked up. Employees saved themselves an average of one hour a day – not to mention a small fortune in costs – by not travelling to work and, perhaps understandably, found themselves much happier as a result. Few daily routine tasks make people as miserable as commuting according to survey evidence. But it was not just employees gaining either, the new situation appeared to be a win-win situation for employees and employers. Employees saved both time and money and reported an improved work-life balance whilst employers, at least initially, appeared to benefit from higher productivity. As is always the case, the commentariat ran ahead of itself proclaiming the death of the office, the death of the megacity and envisaging a world where employees would scatter to lower priced, larger houses far from the cities and Zoom into meetings when required.

The situation now appears less win-win. Over this year many tech firms – previously on the cutting edge of encouraging home working – have begun to call their employees back to the office. Apple, Google, Meta – and most ironically – Zoom have all increased the number of office days required of staff this year. Partially this reflects something that many economists spotted early in 2020 – one thing that allowed homeworking to operate smoothly in 2020 was the accumulated social capital built up amongst colleagues over many years sitting together in an office. But over time that social capital would deplete and have to be renewed with face-to-face contact. What is more, what worked for previously existing colleagues was tougher for new joiners. Onboarding new staff during lockdowns was far from straight forward.

More generally though, the initial hopes of higher productivity look to have been mistaken. One much touted early report by two doctoral students at Harvard University published in 2020 found that the number of calls handled by call centre workers working from home rose by 8%. But an updated and revised version of the paper published this summer found that actually the call volume fell by 4%. Much of the reported improvement in productivity looks to have been employees actually working longer hours – presumably those saved by not commuting – rather than working more efficiently in the same amount of time.

Recent studies suggest, as will be obvious to anyone who spent much time on Zoom or Microsoft Teams in 2020 and 2021, that online meetings are distinctly inferior to in person ones.

Understandably working from home tends to reduce contact between employees leading to less collaboration and fewer examples of learning from co-workers.

It is perhaps no surprise that the dial has shifted back to offices. But the dial can only shift so far. Once the working from home genie was out of the bottle, it was hard to put back.

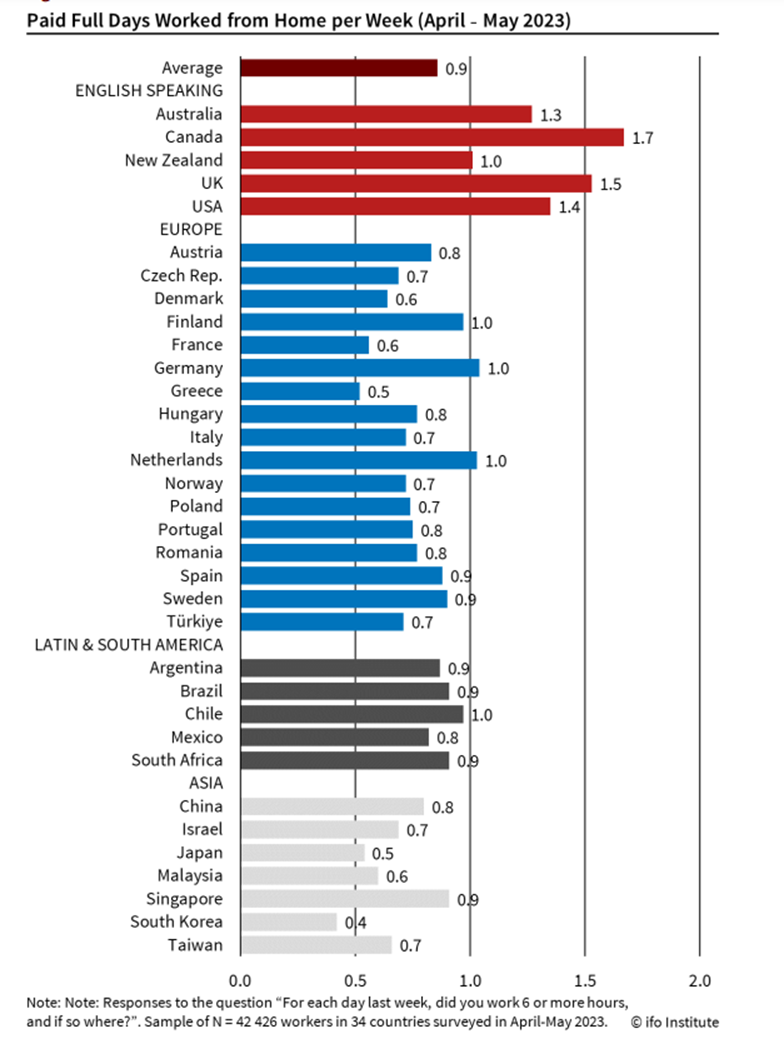

A recent study of global office based workers with at least a university degree found that home working, which was statistically negligible prior to March 2020 is here to stay. Although with marked regional differences.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Cevat Giray Aksoy, Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, Steven J. Davis, Mathias Dolls, Pablo Zarate: “Working from Home Around the Globe: 2023 Report,” EconPol Policy Brief 53, July 2023.

It has taken off to a greater extent in the English-speaking world and much less so in Asia.

What is more, employees in the English-speaking world would generally like to work from home even more with the average desire being over two days a week.

Britain, along with Canada, is something of a global outlier.

And with the jobs-market still tight, British bosses are unlikely to be able to compel office workers back towards the global average of less than one a day a week of home working.

Given it is likely here to stay, the rise of home working is likely to have profound implications on the structure of the economy with important implications across asset classes.

In many ways the rise of remote working is the most important development since the development of the railway. Before railways workers had to live within a reasonably close distance of their place of work with most travelling by foot. Until the 1830s the vast majority of workers in Britain lived within three or four miles of their employers. Once the ability to travel relatively quickly and relatively cheaper was an option, things changed. Cities grew with the birth of the modern suburb; what had previously been small market towns filled up with commuters and house prices entered a period of real, after inflation, price falls that lasted from the mid nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. As railways expanded the commutable areas around centres of employment from either or so mile circles to thirty or fourty mile circles more space became commutable and more housing available. Only when commuting times ceased to fall and started to rise with congestion in the mid twentieth century did long term house prices stabilise and indeed begin to rise.

1.5 days a week on average of home working for office based workers is not such a large change as the birth of modern mass transport but it is still a major one, a 30% fall in average footfall in city centres on any given weekday will have a major impact – and varying impact – on different firms.

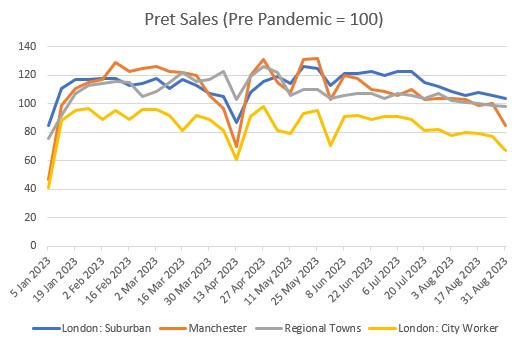

The most obvious loser is the kind of firm that has specialised in serving office workers directly. Pret A Manger, the office worker’s sandwich shop of choice, is perhaps the best barometer. Since early 2021 it has supplied weekly data on sales by location type to the Office for National Statistics.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Pret A Manger, Office for National Statistics, August 2023

More than three years after the pandemic hit, sales in central London are still down more than 30% on pre-pandemic levels and those in Manchester around 15% below where they were. Given the previous business mix, a small rise in suburban sales is not enough to offset this.

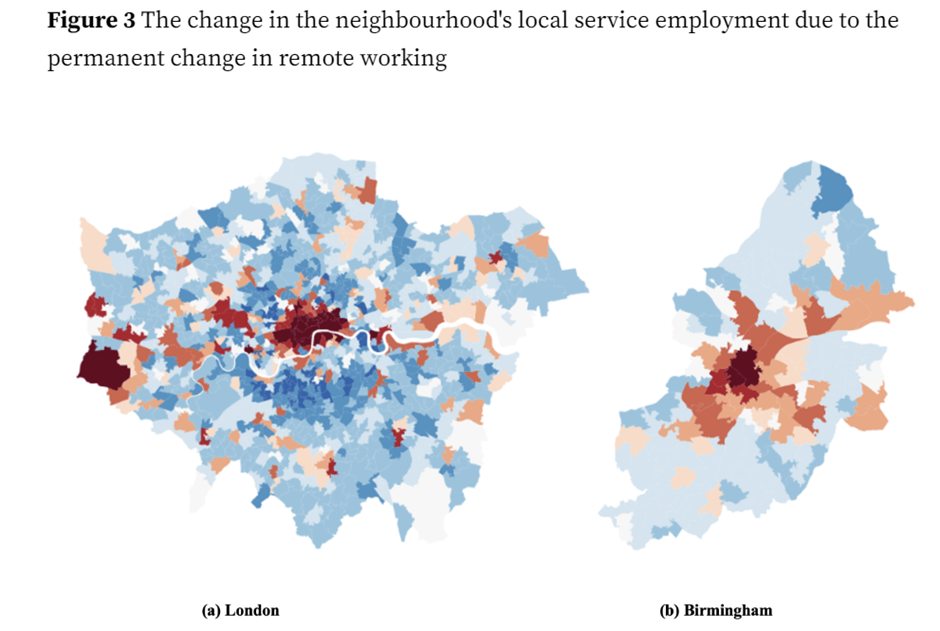

Service sector employment patterns show a broad fall in city centres and growth around the edge of major cities.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, The Centre for Economic Policy Research, Remote working and the new geography of local service spending, November 2022

The railways too have not seen a return to the pre-pandemic norm. Quarterly journeys are 17% below the level of early 2020.

The bigger impact though is not on the people who service office workers but on those who own the buildings that they commute to. Faced with a 30% fall in occupancy levels many firms are looking to downsize.

According to CoStar, a consultancy, the London office vacancy rate has risen to 9% this summer – up from just 5% in March 2020. The volume of deals remains well below pre-pandemic levels with several major firms consciously choosing to downsize their office footprint. Estate agents Knight Frank reckon that office rental yields are likely to fall further in the coming year for 13 of the 15 sub sectors they track.

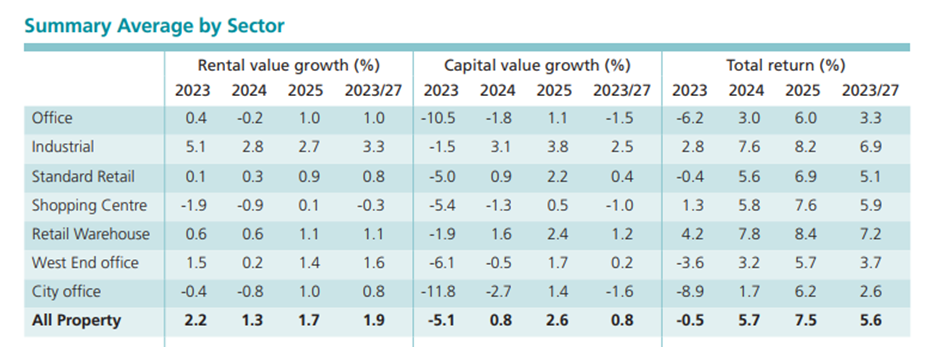

The consensus property forecasts from the Investment Property Forum make for grim reading.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Investment Property Forum, Summer 2023 Survey of Independent Forecasts for UK Commercial Property Investment, September 2023

In a world of five per cent plus interest rates, an average annual 3.3% total return on office property – including rental income and capital gains – between 2023 and 2027 appears very low. Higher rates would always have been tricky for property investors, but the changing patterns of work have doubled up the problems faced by the office sector.

Zoopla, the online property broker, reckons that homeworking is continuing to reshape the housing market too – even against a backdrop of rising mortgage rates and falling prices overall. Commutable but cheaper areas are retaining their value and even see modest house price growth even whilst the overall market stagnates. If an office worker was previously happy commuting an average of 30 minutes each way five times a week, then commuting 45 minutes each way three times a week still represents a 30 minute weekly saving.

The higher inflation brought about by the pandemic will eventually fade, Government debt levels will eventually stabilise. But the changes in economic geography brought about by the rise of hybrid working are here to stay. Business models across many sectors will have to change in the years ahead to adapt.

|

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING 27th September, US Durable Goods – US consumer spending has weathered rising interest rates and a more troubled economic backdrop surprisingly well. But there are increasing signs that firms are being forced to cut back on their investment spending. Durable goods orders tend to give a good read on the state of capital spending. Investment spending by firms is a relatively small share of overall GDP but a volatile one worth watching. 29th September, British GDP – This month the Office for National Statistics rewrote recent economic history by revising down the size of the fall in output in 2020 and revising up the speed of the recovery in 2021. The end result left the level of national income almost 2% higher than previously thought. But despite the better than expected historical performance, 2023 is proving to be a rough year. Whilst an outright recession may be avoided, growth looks to be, at best, sluggish. 9th October, China Trade Data – China, even after the de-globalisation of recent years, is still the single largest manufacturer in the world and the centre of many supply chains. Trade data released in October should give sense of how global manufacturing is coping with higher costs and higher interest rates. |