SORBUS spotlight: The Advanced Economy Divergence

At the turn of the year, the Western economies were braced for a nasty recession. But as the halfway point of 2023 ranges into view, forecasts have become a touch more optimistic. Whilst no one would call the economic outlook positive, it is at least not as negative as once feared. The United States, the Eurozone and, hopefully, Britain should all be able to avoid a technical recession – usually defined as two consecutive quarters of falling economic output – even if, for many firms and households, the situation will still certainly feel like one.

Lower than expected global energy prices have helped bring inflation down from its highs and provided some respite to both household finances and the bottom lines of businesses. But whilst that story is a global one, when it comes to macroeconomic policy important differences are beginning to emerge.

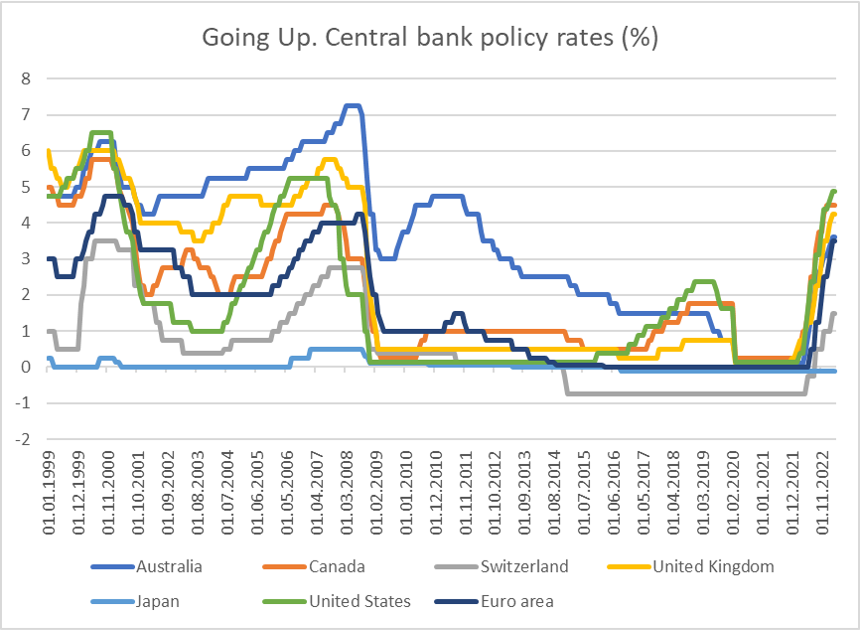

When the economic historians of the middle part of this century look back on the post-pandemic years one thing they will almost certainly alight upon is the rapid change in global central bank policy.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, BIS (data as at: 01/06/2023)

The tightening of policy, via the raising of interest rates, that began in late 2021 and continued throughout 2022 and into 2023 was both globally synchronised and on a pace not seen in decades. Faced with uncomfortably high inflation and tight jobs markets, short term interest rates have risen to levels that markets – and indeed central bankers – had not expected to see again for many years. As recently as 2020, Bank of England officials spoke openly of ‘the new normal’ for interest rates being around 2-3% rather than the 5% seen as typical before the 2008 crisis.

The full impact of the rate rises experienced over the past 18 months has not yet been felt, although central bankers hope it will be enough to return inflation to more normal levels over the course of 2024. Unfortunately, the data does not support their breezy optimism. Inflation was over 10% for seven straight months in the UK and has infected wage and service price expectations; these are terribly sticky. Inflation has never before been reduced down from these levels without interest rates at levels that cause recession. In the trade-off between persistent inflation and recession central banks have decisively selected the former as their policy basis.

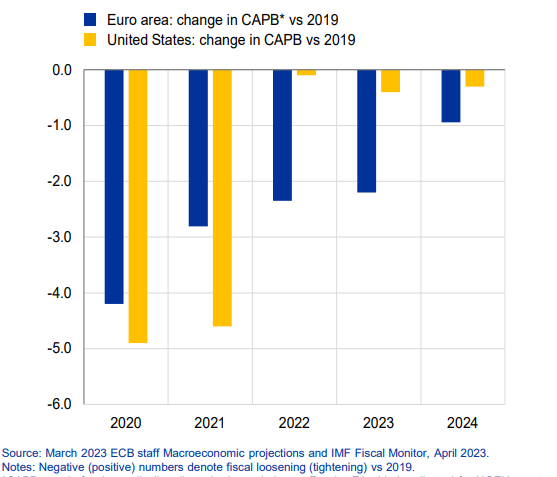

But if the global monetary policy has been synchronised, global fiscal policy is beginning to diverge. The chart below shows the cleanest measure of the stance of fiscal policy – the change in the cyclically adjusted primary budget balance as a share of potential national income. That is to say a measure of the government’s budget deficit excluding the cost of debt interest payments and adjusted for the state of the business cycle. It tries to capture how much discretionary fiscal stimulus any government is injecting into its economy via policy at any point in time.

source: ECB (data as at April 2023)

The US fiscal approach was to go for a large injection of extra demand into the economy in 2020 and 2021. The result was both a faster economic recovery and a more entrenched inflation problem in 2021 and 2022. But despite the continuing rhetoric of the Biden administration, US fiscal support became much more scarce in 2022 and is expected to remain so in 2023 and 2024.

By contrast, the collective fiscal support of the Eurozone countries has taken a different path. Whilst less generous – although still large in 2020 and 2021 – it has remained more consistent over the course of 2022 and is expected to in 2023 and 2024.

Monetary policy is tightening globally but whilst fiscal policy has also tightened in the United States, it remains materially looser in Europe.

It is this divergence in policy which helps to explain an under remarked upon divergence in economic outlooks.

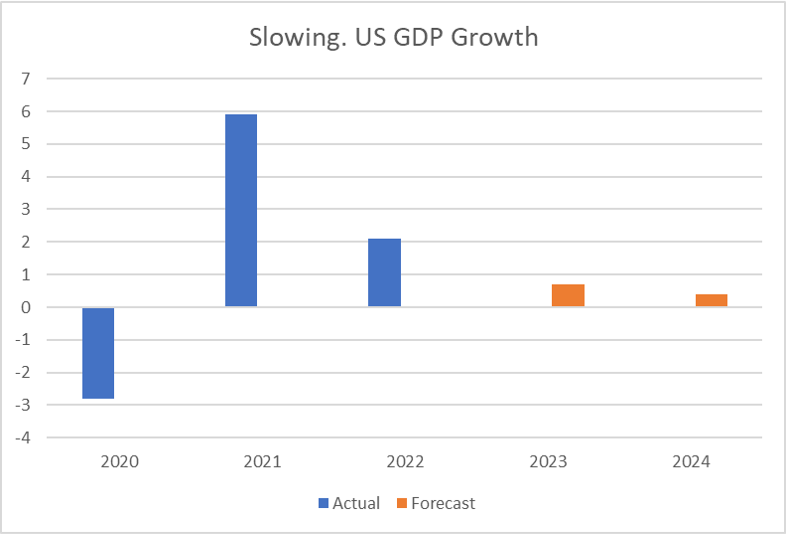

Fears of a US recession appear, for the moment, overblown. But the slowdown in the US economy is still apparent.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, The conference board (data as at 01/06/2023)

The US economy motored ahead with growth of almost 6% in 2021, easily making up the losses in the pandemic and still managed a robust 2.1% last year at a time when much of the global economy was stalling. This year however the Conference Board, the most respected US forecaster, has pencilled in an expansion of just 0.7%, followed by less than half a percentage point in 2024.

US consumer spending is expected to virtually stagnate over the coming two years as higher interest rates take a bite out of household incomes and the jobs market loosens, slowing wage growth further. That will all no doubt be welcome news to a Federal Reserve desperate to cool inflation but is unlikely to be greeted by firms dependent on the US market or indeed to American households. The US economy has been the bright spot in the post pandemic global economy but that star is now starting to dim.

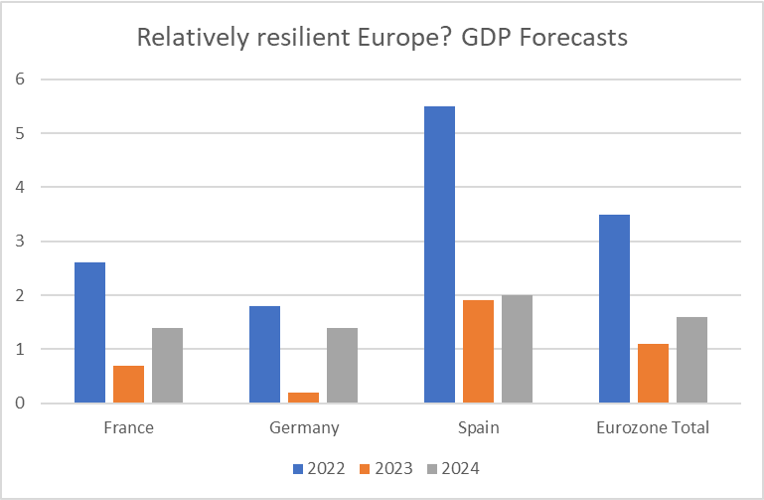

The good news is that buoyed by lower energy prices and more generous fiscal support, the European economy is in better shape.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, European Commission (data as at: 01/06/2023)

After a tough 2023, European growth is expected to rebound in 2024. Recent negative headlines about unexpectedly weak German GDP numbers miss the bigger picture that overall European growth looks to be resilient and that the Eurozone is expected to grow twice as quickly as the United States over the coming 18 months. Whilst annual growth of around 1.5% is nothing to get too excited about, it compares very favourably to the expectations across the Atlantic.

Europe’s real immediate economic advantage over the United States in the coming 18 months is the nature of its inflation problem. Whilst the US’ inflation was primarily a result of an overheated economy and very tight jobs market, Europe’s was more of an energy price story. As energy prices fall so too will inflation, with less need for more aggressive monetary policy tightening. The US experienced a sugar rush of growth in 2021 and 2022 but is now feeling the consequences, Europe’s recovery from the pandemic was less spectacular but may well run on for longer.

Britain, as is so often the case, is stuck somewhere in between. It had the misfortune to suffer from a tight jobs market pushing inflation higher and to feel the full impact of the energy crisis. The result is that whilst Europe’s interest rate rises may be near their peak, Britain’s are likely to follow the United States higher still.

British fiscal policy however is following a more European path with support being withdrawn at a much more gradual pace than in America.

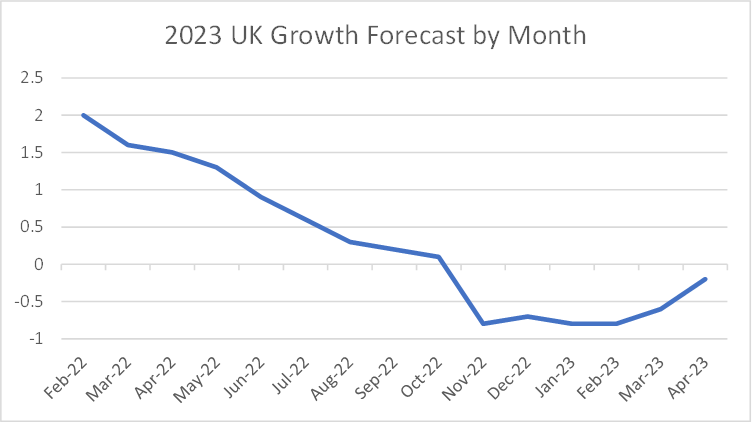

The best way to get a sense of how expectations about Britain’s economy have developed is to look back at the consensus forecast for growth in 2023 and how it has evolved over time.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Gov.uk (data as at: 01/06/2023)

Back in February last year, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the consensus was reasonably positive with growth expected to be around 2%. The energy price spike and the fall in household incomes afterwards saw growth hopes being continually revised down towards a virtual stagnation by the Autumn. The short-lived Truss government – and the turmoil in the market for British government debt which preceded it – led to expectations of an actual recession.

The story since then has been one of rising expectations. This of course all needs to be kept in context – it was after all only a year ago that people hoped for growth of around 1%. A virtual standstill in economic output is a poor outturn judged against that benchmark even if it is better than a contraction.

Stepping back to the level of global macroeconomics, the narrative of 2023 is likely to shift once again. The year opened on a low note with talk of a global recession, that gave way to a sense of relief that things were not turning out quite as badly as feared. Over time that sense of relief will likely dissipate as the still grim nature of the global economy becomes apparent. But that overall narrative hides important differences – not least the relative resilience of Europe’s recovery.

|

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING 13th June, British Labour Market Stats – The jobs market is the most important British indicator to watch. Headline inflation will fall sharply over the coming year as the energy price surge drops out of the figures. But underlying inflation pressures, emitting from wage growth, could well push the Bank of England into further tightening. The pace of wage growth and the number of vacancies (as a proxy for the extent of labour undersupply) advertised are the key measures to watch. 14th June, US Federal Reserve – Four times a year the US Federal Reserve releases its medium-term forecasts. June is one such month. The Fed should give markets a better steer on the likely peak level of US rates and how much further is still to come. 15th June, ECB – The European Central Bank meets the very next day and is likely to sound more dovish than their American counterparts. |