SORBUS spotlight: A modern version of an old story.

Bank runs are almost as old as banking. But familiarity does not make them any more comfortable when they happen. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank, the distressed sale of Credit Suisse and turbulence in the wider financial system had left markets on edge and rekindled memories of 2007 to 2009.

To understand the bigger picture, it is worth stepping back and looking at both the immediate triggers of the current problems and their longer term drivers. Whilst a full-blown banking crisis is still far from the base case, the events of the past couple of weeks may well be enough to slow the pace of central bank tightening ahead.

The basic business model of banking is what economists tend to dub ‘maturity transformation’. They transform short term liabilities into long term assets by accepting deposits withdrawable on demand and making longer term investments of loans. That is a crucial part of the functioning of the financial system and one for which they are, in theory, rewarded with a stream of profits. But those profits are far from risk-free, the model itself contains an always present danger in the mismatch between short term liabilities and longer-term assets. As anyone who has watched either It’s a Wonderful Life or Mary Poppins knows, if enough depositors get twitchy at the same time and move to withdraw their deposits at the same time then the bank will not have ready cash to meet the flow.

The dynamics of a bank run can quickly become self-reinforcing. It is an unusual case where acting seemingly irrationally can be the entirely rational thing to do. If rumours spread that a bank is in trouble and it appears that, say, 50% of deposits are likely to be withdrawn in a short period of time, then it makes perfect sense to want to be one of the 50% of deposit holders who gets their cash out even if one suspects that the rumoured problems are overblown.

Silicon Valley Bank, which had a balance sheet of around $200bn, seemed – just 18 or so months ago – to have a solid business model. It was not just a bank in Silicon Valley but was almost the bank for Silicon Valley. It had become the go-to provider of banking services for venture capital backed, California based tech start-ups with a solid business in tech companies outside of the Sunshine State too. It provided a high level of client care, hands-on relationship management and helped connect firms with the potential to work together. It was very much a part of the tech community. It was that community which helped bring it down so quickly. Whilst the bank almost certainly thought of itself as having thousands of individual depositors, many were actually funded by the same few dozen venture capital firms. The real economic decision makers when it came to financial matters, such as where firms held their cash, numbered in the hundreds rather than the thousands. When a few large VC funds told their investees to move their cash many others quickly joined them.

The more interesting question is not how the run happened so quickly but why it took place at all. That involves stepping back to look at the longer term factors behind SVB’s recent troubles, which go much deeper than the tech sector.

The really interesting difference between SVB’s failure and the banking crisis of 2007 is that this one does not involve the same kind of reckless lending decisions and loans gone bad. The subprime crisis was at least easy to grasp – banks had extended loans to people who could not afford them. This time around SVB’s assets consisted almost entirely of supposedly ultra-safe long dated US government bonds and government-guaranteed mortgage backed securities. This is not really a story about credit risk.

Once upon a time US commercial bankers used to joke that they lived by a 3-6-3 rule: pay depositors 3%, charge borrowers 6% and always be on the golf course by 3pm. But in a world of ultra-low interest rates, the 3-6-3 rule no longer applied.

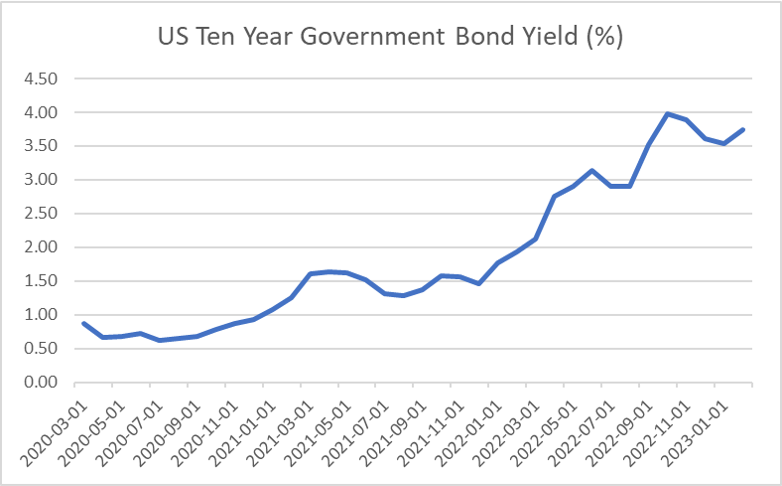

SVB did not really operate as the textbook model of a bank suggests. It paid depositors very little – although it did offer a high level of service – and it did not really make many loans at all. Instead it bought long dated safe bonds. The rule was less 3-6-3 and more – before 2021 anyway – 0-1.5-0 – pay depositors nothing and earn 1.5% from the yield on US government debt, with little hope of making it to the golf course in the working day.

That model seemed to work. Customers were happy enough with the bank’s services that they did not demand a high return on their cash balances and the bank itself seemed to be earning – just about – enough from its ultra-safe long term assets to generate a profit. But the pandemic and its aftermath put paid to that.

The initial impact of the pandemic seemed like a blessing for SVB. Money poured into VC funds and via their investee firms into SVB leading to rapid expansion in its balance sheet. But after that came the rise in inflation and related rapid tightening in central bank policy.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (data as at: 21/03/23)

As interest rates rose the price of long-dated bonds fell leading to mounting potential losses on SVB’s balance sheet. Of course, if those bonds were held to maturity then there would be no loss but if they were forced to sell underwater then that loss would be realised. As the scale of the potential losses climbed higher, depositors began to get twitchy and with each withdrawal potential losses had to be crystallised as bonds were sold to cover the outflow. At that point the bank run dynamics kicked in and the rational thing for depositors to do became to act irrationally.

In the aftermath of one banking collapse, nervous depositors began asking who might be next. In the US both First Republic and Signature Bank, both of whom have pursued similar investment strategies to SVB, were first in the cross hairs. In Europe attention focussed on Credit Suisse. In many ways Credit Suisse was to billionaires what SVB was to tech start-ups: the go to place to keep deposits that offered a high level of customer care and understanding. And billionaire money, like VC funded start-up money, means a relatively small number of economic decision makers are involved. In some ways CS has suffered from a slower moving version of the run dynamics that brought down SVB over the past few months. One not helped by a well-publicised series of regulatory problems and investment missteps over the last year. Still, eventually the nerves of depositors across the global system will settle. The larger, remaining, issue will be the fallout from the rise in interest rates that began in 2021.

From 2009 until 2021 the world grew used to an age of ultra-low rates and whilst 12 years may not exactly be an eternity it was long enough for business models to grow and new firms to emerge. The problem now is that business models which suited an age of cheap money may struggle in a world of more historically normal interest rates.

Banks that overinvested in long dated assets, funded via short term liabilities are one potential casualty, tech companies – even very large ones – that rely on cheap credit and never ending sources of VC money to fund current losses, whilst hoping to build a sustainable model, are another. WeWork and Uber – both briefly hailed as the beginning of whole paradigms – are much less attractive propositions in the current climate than they were as recently as 2019. Commercial property firms buffeted by not just the rise in rates but also the shift in commuter patterns brought about by the rise of working-from-home are yet another potential victim.

It will take some time for the full picture to emerge but in the short run, the most pressing question is whether the near-miss financial crisis of March will be enough to prompt a change in policy from central banks. Over the past two years the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have tightened policy at the quickest pace in three decades to try and cool inflation. But now inflation looks to have peaked (at least at the headline level) and the consequences of rate rises are being felt across financial markets. Some commentators have speculated that the financial fallout may even be enough to push central banks towards U-turning and cutting rates. That seems unlikely. The European Central Bank pressed ahead with tightening last week even as Credit Suisse tottered and banking shares fell.

But even if the banking problems are not enough to force central banks into cutting rates, they may well be enough to slow the pace of future hikes.

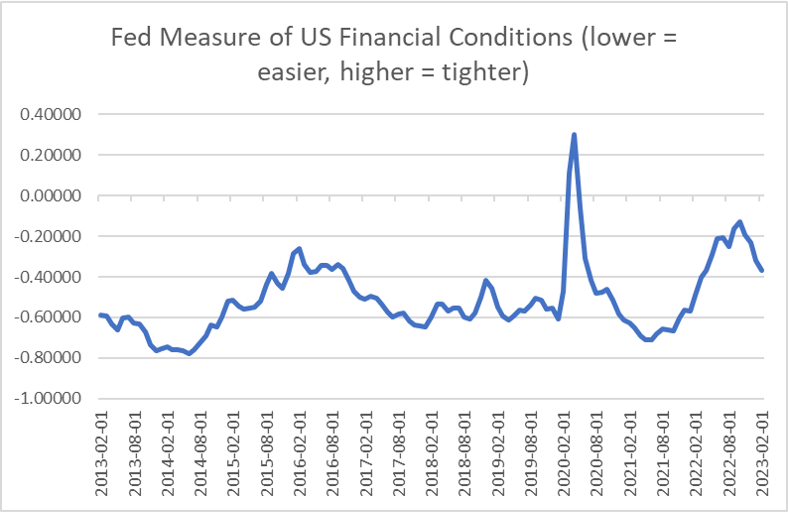

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (data as at: 21/03/23)

Commentary from rate-setters at the US Fed over the past few months has contained more than a hint of frustration. Even as they have hiked rates, financial market participants have often been in a buoyant mood. Equity price rallies and markets convincing themselves that the tightening is almost done have both tended to keep overall financial conditions easier than policymakers would like. Central banks, it should be remembered, have been increasing interest rates in order to tighten financial conditions to slow down the hiring and investment plans of firms and ultimately economic growth. Bring down price pressures and inflation requires taking some heat out of the economy.

The nasty shock delivered by SVB – and now Credit Suisse – if it does lead to tighter financial conditions makes their job easier. If, and it is still an if, credit and financial market conditions do materially tighten in the weeks ahead then that will indeed lead to a slowdown in economic growth. But that is a feature not a bug of what central banks are trying to achieve.

WHAT TO WATCH FOR IN THE NEXT MONTH 31st March: Eurozone inflation – Eurozone inflation, to a greater extent than its British and American equivalents – has been mostly an energy price story over the past year with tight labour markets contributing less. As energy prices fall, there is room for European inflation to fall faster than in the Anglo-Saxon economies. That could give the ECB the space it needs to pause rate hikes earlier than many have feared. 13th April: British GDP – February’s GDP numbers will be worth scrutinising closely. The January numbers were more upbeat than expected, although much of that may simply have been a rebound from the strikes that hamstrung many sectors in December. A strong set of February numbers should ease fears of a recession, but a weak February could see a renewed growth scare. |