SORBUS spotlight: The five big questions for 2023

At first glance, the global economy of 2023 looks set to an unwanted repeat of 2022 – a year dominated by uncomfortably high inflation, slowing growth, rising interest rates and squeezed consumers. But amid the gloom there are tentative grounds, at the global level, for hope that the worst may now be in the rear view mirror. Peak inflation, at least as measured by the annual rate of change, has almost certainly been passed. The US, one of the major motors of global growth, may yet avoid recession. China, the other major driver of global GDP, has abandoned its zero-covid policy that was still disturbing global value chains. Even in the most optimistic scenarios, 2023 looks set to be tough for both consumers and firms but it may not be as disastrous as some fear.

Five major themes will dominate the year.

Inflation

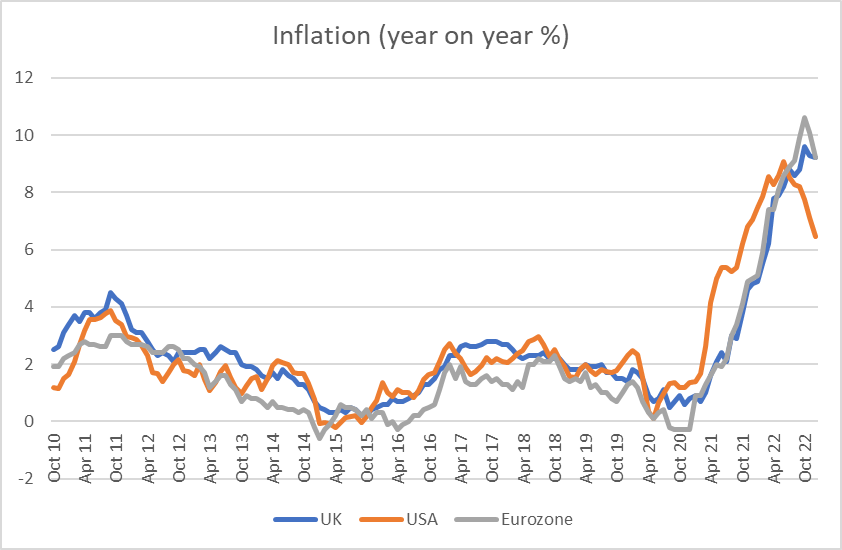

Across the advanced economies, inflation looks to have peaked.

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, OECD (all data as at: 30th January 2023)

Partially this is simply the impact of what statisticians dub the ‘base effect’ – given the scale of price rises seen between 2021 and 2022, then the rate of change was always likely to slow in 2023. But some of the real factors which drive inflation to four decade highs also look to be unwinding.

After three years of extreme disruption, global supply chains look to be in better shape. The chip shortage which has hamstrung manufacturing and led to a shortfall of new cars, driving used car prices to frankly ridiculous levels, looks to be finally easing. Whilst energy costs remain historically elevated, the pace of increases has slowed or even, in some areas reversed.

The US – which was the first advanced economy to see soaring inflation – has experienced the fastest fall in the rate of change of prices so far.

But the world is not out of the inflationary woods yet. Core inflation – excluding volatile components such as food and energy prices – remains at its highest pace since the early 1990s in most countries. Tight labour markets, driven by worker shortages and hiring difficulties, continue to see wage growth rising at a fast clip; not fast enough to protect workers from a rising price level but fast enough to add to business costs.

Assuming no further energy price shocks, inflation is likely to end the year closer to 5% than 10% across Europe and North America. Whilst welcome that is still around twice as high as central banks desire.

One big question facing the advanced economies in 2023 is; how entrenched has inflation become? If core inflation, and wage growth, begins to tick down in the second half of the year, central banks will breathe a little easier. If it remains around current levels, then further rate rises to slow jobs markets are likely.

US Growth

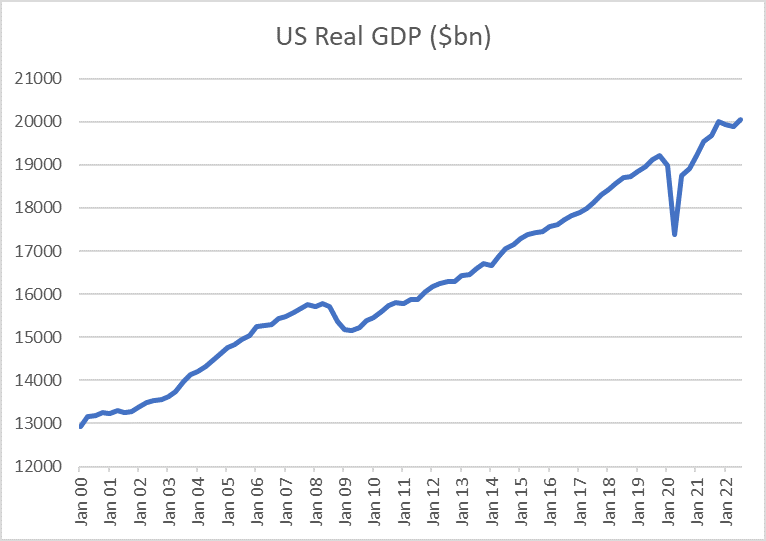

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (all data as at: 30th January 2023)

In many ways the US recovery from the pandemic-induced recession of 2020 has been extraordinary. After the 2008/09 downturn the level of output never returned to its previous trend. In sharp contrast, the high levels of monetary and fiscal stimulus applied in 2020 and 2021 saw the level of US output not only regain the pre-recession trend very quickly, but even surpass it.

The worry though – with the jobs market tighter than ever and inflation high – is that the country has had too much of a good thing – growth has exceeded potential and needs to be slowed to bring inflation down to more comfortable levels.

Certainly the Federal Reserve has been tightening policy aggressively to cool the jobs market. The big question for 2023 is whether inflation can be lowered sufficiently without prompting a recession. In the jargon, can the Fed achieve a ‘soft landing’?

There are two key variables to watch: the jobs market and asset prices. The Fed hopes to lower wage pressure by reducing the number of advertised job vacancies without causing a spike in unemployment. That will be tough. Monetary policy is a blunt tool rather than a scalpel. Raising rates to the point where firms cancel hiring plans but do not engage in layoffs is not straight forward.

More generally, it is worth keeping in mind the mechanism through which the Fed is hoping to engineer this outcome. By tightening policy it aims to tighten financial conditions in the US to discourage borrowing and expansion. The worry, increasingly expressed by the Fed’s governing body, is that financial markets continually react to good news on the inflation by assuming less monetary tightening will be required and rallying higher. Higher stock prices, all things being equal, imply easier financial conditions and make the Fed’s task harder. In other words, the more buoyant markets are the more the Fed may feel the need to press back against them.

European tension

Europe finds itself in a worse position than North America. It is both more exposed to the energy price shock and more exposed to China’s slowing economy. Export markets look soggy whilst business costs have increased rapidly.

Europe’s labour markets, whilst not as tight as that of the United States, are also adding to price rises and pushing the European Central Bank towards more tightening.

But the macro picture in the Eurozone is further complicated by the divergence between its member states.

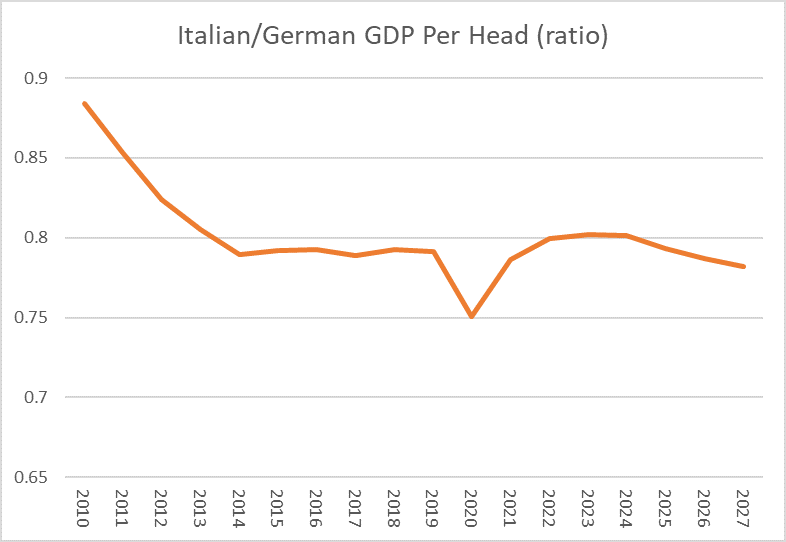

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, IMF (all data as at: 30th January 2023)

A look at the ratio of Italian to German GDP per head since 2010 (with IMF forecasts out to 2027) presents a worrying picture.

At the height of the Euro Crisis in the early 2010s, Italian income per head dropped from almost 90% of German levels to under 80%. That decline was eventually arrested by the mid 2010s but risks opening up again in the 2020s.

Diverging economic paths – especially given Italy’s new, more populist leaning government – risk reopening questions about the stability of the Euro itself.

Europe as a whole should be in better shape by the end of 2023 than at the end of 2022. But watching the performance of individual countries will be as important as keeping an eye on the progress of the entire single currency area.

China

China had a rough 2022. The bursting of a real estate bubble coupled with continuing covid-related lockdowns, pushed growth to a multi-decade low.

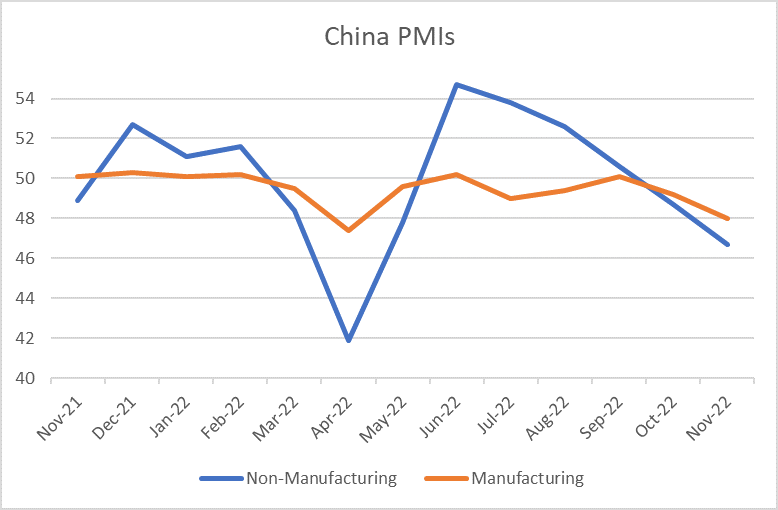

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, National Bureau of Statistics of China (all data as at: 30th January 2023)

The sudden reversal of policy on the pandemic may give growth a needed fillip.

Purchasing Manager Indices (where a reading of above 50 signals expansion and below 50 contraction are the best timely indicators on Chinese growth.

Over the first quarter of 2023, the authorities will be hoping to see such indices heading up quickly. That will be tough. The sudden switch in public health policy has increased uncertainty amongst both corporate and consumers and left them wondering if another U-turn may follow.

China’s growth rate is unlikely to return to the kind of levels seen in the mid 2010s, but the Party will almost certainly be prepared to apply fresh stimulus to prevent them falling too low. The PMIs, together with export figures, will give the clearest signs of how the economy is performing in 2023.

The dollar

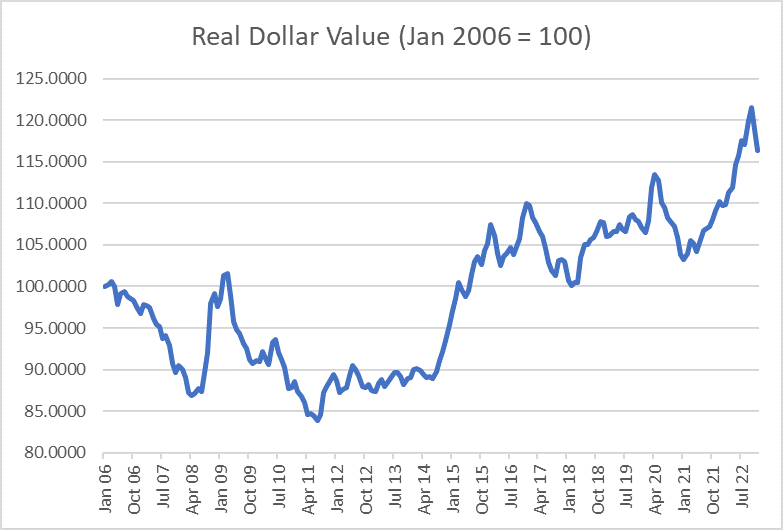

The dollar has been on an incredible run.

Source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (all data as at: 30th January 2023)

Measured against a broad basket of other currencies, it soared to a multi decade high in late 2022 – up almost 15% in just over a year.

Behind that move sat two fundamental factors. First, as the US emerged first from the recession of 2020 and was the first major economy to experience high inflation, it was the Federal Reserve that led the way in raising interest rates. Those higher US rates attracted inflows of capital pushing the dollar’s value northwards. That was then compounded by rising global risk aversion and further boost to the dollar given its traditional safe haven status.

As evidence has mounted that US inflation has peaked and as the rate differentials between the US and other economies has narrowed, the dollar has given back some of those gains.

Whilst a strong dollar is great news for American consumers and tourists, it tends to be less welcome for global growth. It puts pressure on the balance sheets of foreign firms with USD borrowings and usually takes a bite out of the export earnings of emerging markets.

The value of the dollar is a key price to watch in 2023. A further bout of dollar strength would signal trouble ahead for the global economy whilst a gradual decline would suggest that the Fed is on track to achieve its soft landing.

|

WHAT TO WATCH FOR IN THE NEXT MONTH Tuesday, 31st January: French, German and Italian GDP – the performances of individual countries all matter but more important is evidence of economic divergence. Whilst France’s nuclear power provides some insulation from the energy price shock, both Germany and Italy are heavily reliant on Russian natural gas. Watching how they cope with this shock will be crucial in 2023. Wednesday, 1st February: China manufacturing PMI – paying too much attention to any given month’s figures is usually a mug’s game. But the authorities in Beijing are heavily banking on the January PMI heading above 50. Anything below will ring alarm bells about Chinese growth. Thursday, 2nd February: Bank of England Meeting – the Monetary Policy Committee will hold its first meeting since mid-December in early February. The six week break – and the accumulation of new evidence – should see them wanting to send a clear signal about the likely extent of monetary tightening to come. Whilst more rate rises are likely, the pace may now begin to slow. |