SORBUS spotlight: How long will the recession last?

Economists are very bad at spotting recessions in advance. The Treasury publishes a monthly roundup of independent forecasts going all the way back to 1985. The really striking thing when looking back over it is that consensus forecasts failed to spot the recessions of 2020, 2008 or 1990 until months after they had already begun. 2020 can perhaps be forgiven – recessions do not usually arrive as a bolt from the blue driven by public health policy and lockdowns but in hindsight, the warning signs were flashing in both 2008 and 1990. 2022’s downturn is in the same category, the collapse in consumer confidence that began in the Spring should have rung more alarm bells with forecasters. Real household incomes and consumer sentiment have been undergoing a steep fall for many months, as we have previously highlighted, and it should come as no surprise that spending is now being pulled back.

Whether they managed to spot the recession in advance or not though, economic forecasts are still useful. If nothing else, understanding the forecasts of economic policymakers helps give some clues as to how they are likely to respond to developments. Knowing their base-case and working assumptions can give an insight into how they will react to better or worse than expected data in the months ahead.

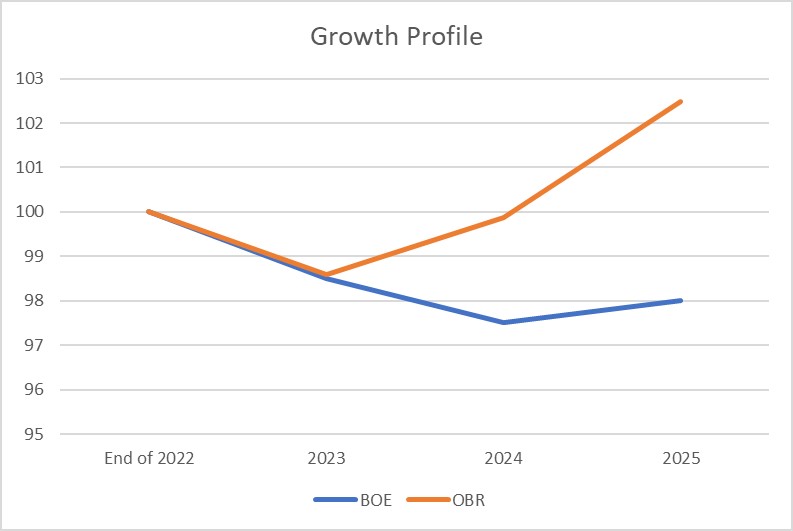

Over the last few weeks both the Bank of England (BOE) and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the government’s independent forecaster, have updated their own numbers. The BOE in its November 2022 monetary policy report and the OBR in its November 2022 economic & fiscal outlook. Whilst they both agree that household incomes are undergoing a historical squeeze and that growth is already moving in reverse, they agree on surprisingly little else.

In fact there is an unusual divergence in their medium term growth outlooks.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

The BOE, as the headline writers seized on back in November, is projecting Britain’s longest recession on record. Whilst the depth will be mild compared to 2008 (let alone 2020), the recession will – in their view – drag on and be followed by a slow recovery. The OBR by contrast, sees a recession which is not only much shallower but which is also over much quicker.

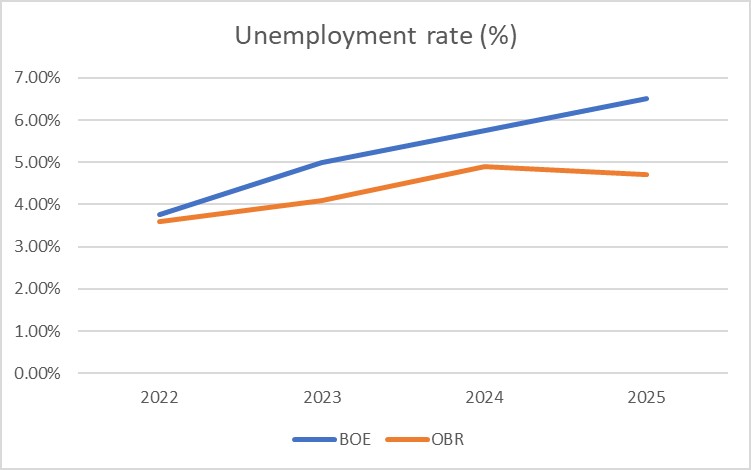

Those very different growth projections point to rather different looking jobs markets.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

In the view of the BOE, unemployment will keep rising for the coming three years whilst the OBR sees not only a materially lower peak but a faster fall in the rate too.

One difference is the assumptions about the state of play when it comes to tax and spending. The BOE’s forecasts predate the Autumn Statement and so, as is always the case, assumed no changes in fiscal policy. Whilst the OBR numbers incorporate the fiscal loosening expected to support growth in the short term and the fiscal tightening of higher taxes and spending cuts expected after the next general election.

But despite this, fiscal policy makes relatively little difference to the numbers for 2024 and 2025. In other words more government support in the short term explains away why the OBR expects a shallower recession in 2023 but does not really adequately explain the big differences over 2024 and 2025.

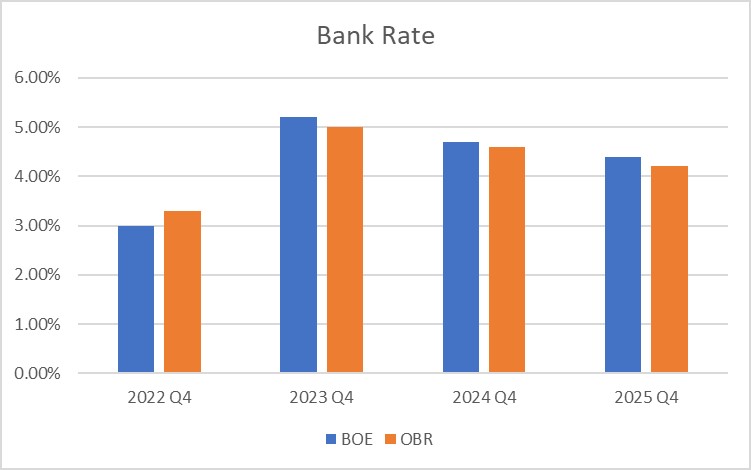

Nor can monetary policy expectations provide an answer.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

Both the BOE and the OBR took their Bank Rate assumptions from the futures curve, the best guide to market expectations of monetary policy. The OBR closed their forecast two weeks later than the BOE, by which time market expectations had come down a bit but the difference is not huge. A 0.2 percentage point difference in expectations over the peak rate that the BOE will get to cannot explain the vast differences in expected growth.

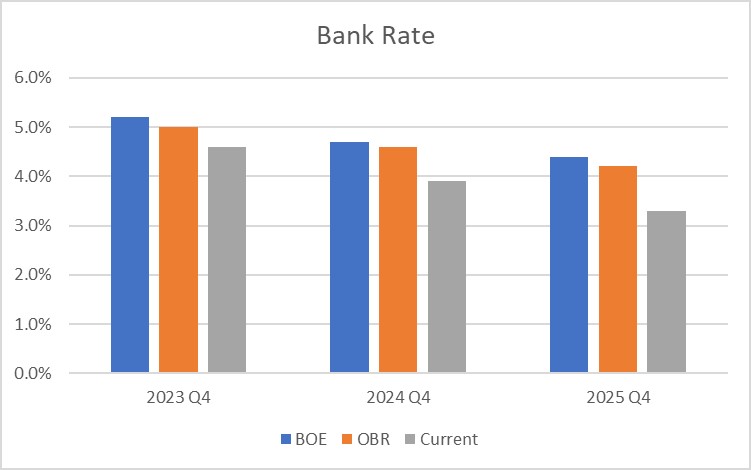

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

And since the OBR forecast, expectations of Bank Rate have come down further in financial markets. The near constant refrain from members of the Monetary Policy Committee that markets have been overestimating the amount of monetary tightening required seems to have finally begun to cut through with rates traders.

To understand the British economy it is usually best to start with consumers and households. Household consumption is, after all, the biggest single chunk of economic output. Both the OBR and the BOE expect a sharp drop in real household income as energy costs, generally higher inflation and higher taxes take a big bite out of incomes, which faster wage growth is unable to compensate for.

But, crucially, the two institutions expect households to react to this fall in different ways.

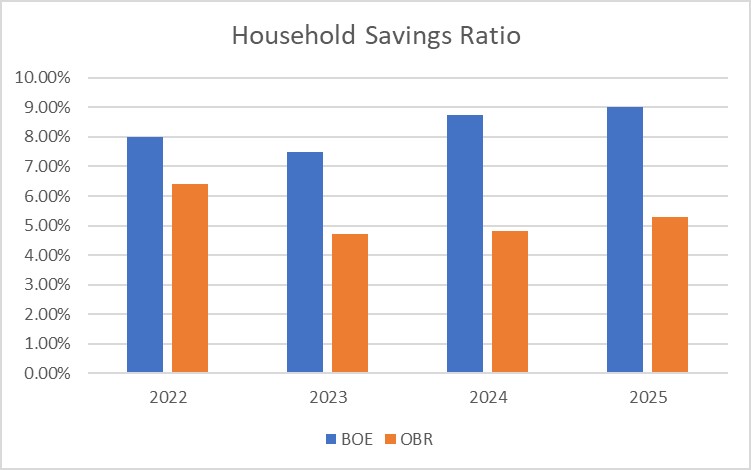

The key variable to watch is the household savings ratio, the percentage of post-tax real income that households – in aggregate – choose to save (or use to pay down debt) rather than to consume.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, BOE monetary policy report Nov 22, OBR economic & fiscal outlook Nov 22.

The BOE expects this ratio to stay reasonably high and indeed to rise in the years ahead whilst the OBR is seeing it falling.

In the OBR’s scenario squeezed households will either run down previously accumulated savings or draw on borrowing to maintain spending whilst the Bank expects a greater consumer pullback.

It will be the behaviour of Britain’s households which determines which institution is right.

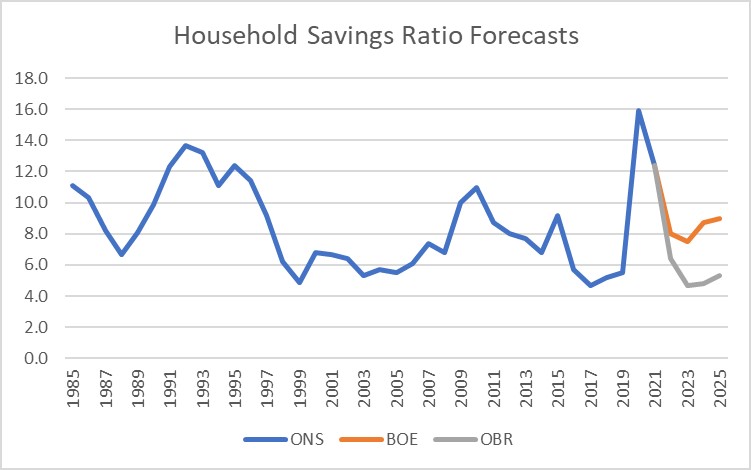

History though rather grimly points to the BOE’s more pessimistic take being closer to the truth.

ONS data from quarterly national accounts

ONS data from quarterly national accounts

The 2020 spike in household savings was clearly unusual – but then closing the shops, pubs and restaurants was also unusual. But what is noteworthy is that in general British recessions such as 2008/09, the early 1990s or the early 1980s have usually been accompanied by rising rather than falling household savings ratios. Low consumer confidence tends to breed slower spending, rising uncertainty over job prospects usually spurs precautionary saving and a poor economic outlook tends to see a tightening of credit conditions and the supply of new lending slowing.

For the OBR to be right, this time needs to be different.

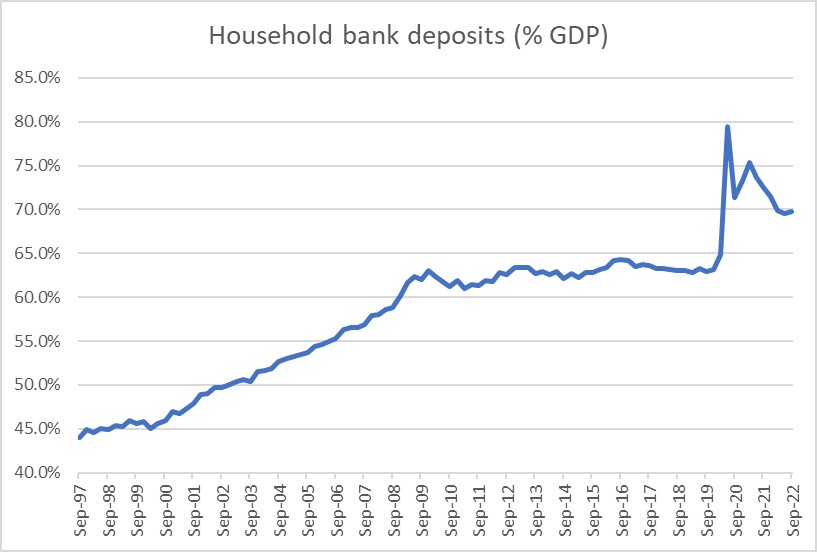

But perhaps it will be? The defining feature of the last few years of the business cycle has been the global pandemic. One consequence of the collapse in spending in 2020 and the enforced staying at home was the accumulation of a large stock of household savings.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, ONS quarterly national accounts, BOE Bankstats

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, ONS quarterly national accounts, BOE Bankstats

Households have been drawing that cash down over the last 18 months at a fairly rapid pace. That suggests the OBR may not be too wide of the mark. On the other hand the most recent data – covering the third quarter, suggest that the pace of that draw down has levelled off.

Few doubt that Britain is in recession. How long that downturn lasts swings on the question of how households will react to falling real incomes.