SORBUS spotlight: two types of global inflation

For months Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England, has warned that Britain is walking ‘a narrow path’ between the risks of ongoing high inflation and the chance of a recession. The Bank, in its latest forecasts, has now accepted that the most likely outcome is for the country to experience both: unpleasantly high inflation and a nasty recession.

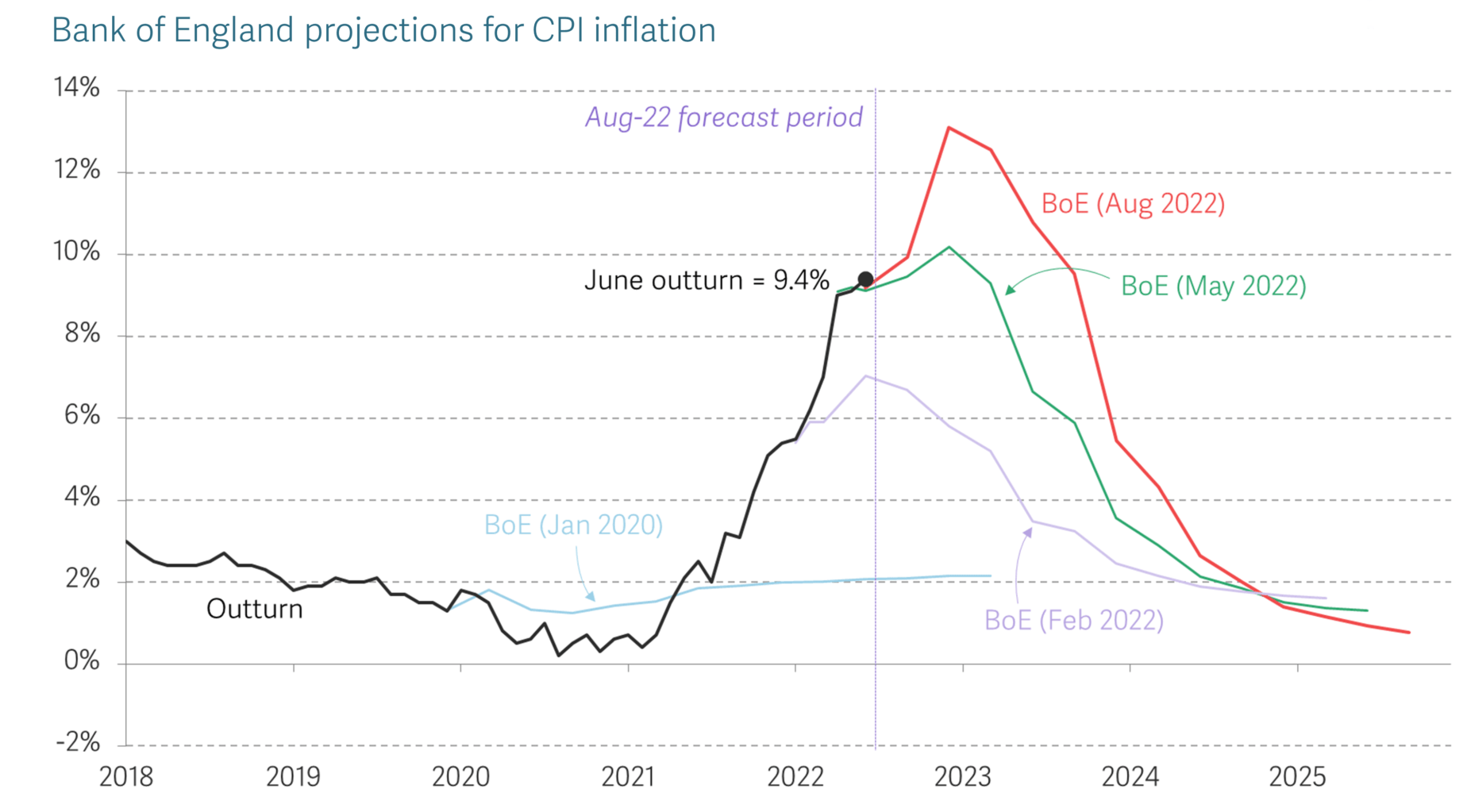

As is becoming an unpleasant habit, the Bank once again revised up its central forecast for the path of British inflation. The peak is now expected to be both higher and to last for longer.

Even the Bank’s grim prognosis of a peak of about 13% may end up being revised higher. Analysis of the likely path of domestic energy bills suggests a peak around 15% is entirely possible.

Inflation is a global problem, afflicting advanced economies across Europe, Asia and North America. But despite similar headline rates of price changes, a look under the hood reveals some important differences.

In broad terms, economies are being hit by two varieties of inflation. On the one hand, there are what economists would usually classify as the inflation emerging from supply-shocks. Pandemic-related disruptions to global manufacturing chains – especially with China’s ongoing zero-covid approach, coupled with rapid rises in global energy and food prices. These sorts of negative shocks have driven up prices in countries reliant on importing energy and food.

On the other, is a more insidious form of inflation – domestically generated price rises coming from the service sector. In this case the story is one of tight labour markets making workers pricier and forcing firms to push up their prices to maintain operating margins.

On a broad level, energy price shocks are now the dominant factor in Europe and services prices in the United States. Britain, uncomfortably for the Bank, seems to have a dose of both. With European-style rises in energy bills and a US-style tight jobs market.

The question facing markets is how long these two different kinds of pressure will last.

Of the two, energy price inflation should dissipate faster. Global energy markets had already struggled to cope with a rebound in global activity in 2021, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Demand for energy recovered much quicker than supply and global inventory levels – especially in gas markets – were rapidly depleted. War in Ukraine and Russia’s curtailing of supplies made an already nasty spike in prices even more painful.

But unless prices continue to rise at their current pace, the immediate inflationary effect will eventually fall back. Energy prices are now expected to remain uncomfortably high for the next few years but at least to begin to stabilise in the coming six months.

For a British household seeing their domestic energy bill rise from under £2,000 to perhaps £4,000 by next winter the fact that prices are not expected to rise much further in 2024 may not bring much comfort. But dealing with the impact of a higher level of prices is a different challenge to dealing with ongoing price changes.

Mounting evidence of a serious economic slowdown in China is bad news for global growth but should, at least, help with inflation. Global commodity prices, outside of energy and food, are now well down from their highs. Copper, the bellweather for wider industrial metals, is down around 20% since early Spring.

A stabilisation in energy prices – after a likely spike this winter – coupled with falls in the price of metals and the slow but steady process of global supply chains establishing themselves all point to supply-shock driven inflation falling in 2023.

The more open question is how long domestically generated services price inflation will persist. That is really a question of how long jobs markets can remain tight for. Counter-intuitively enough, high energy prices may help. A household forced to spend thousands of pounds more on essentials like food and energy is a household that has less room for discretionary spending on consumer services.

The US example is instructive here. The latest data shows the pace of CPI inflation accelerating slightly in the year to July, with prices rising at an annual pace of 8.5%, down from 9.1% the month before. That is still well above a comfortable level and one which will require more Fed hikes to bring down. But it is at least heading in the right direction. As evidence grows that wider US economic growth is slowing, then so is inflationary pressure. It is too early to conclusively say that US inflation has peaked – and there have been a couple of false dawns already this year – but the trend certainly looks more comforting than a few months ago. If the US peak has not been reached then market expectations are that it is almost certainly close. But the fall in inflation is not unmitigated good news; it mostly reflects the slowing of the US economy. As financial conditions tighten and consumer spending begins to weaken the jobs market will gradually loosen, vacancies begin to fall and eventually unemployment will rise. That is the cost of bringing inflation under control.

Inflation rose together across the UK, the US and Eurozone but the underlying drivers varied. The path back down is unlikely to be so uniform as the road up. Taking the Eurozone first whilst the peak in European inflation is unlikely to come until this winter the path to lower inflation looks likely to be relatively quick. The European economy, partially hamstrung by a relatively slow reopening from lockdowns, recovered at a weaker pace in 2021. Jobs markets never got as tight as in the US or Britain. The inflation story in Europe over the past year has mostly been one of imported energy costs and global factors. That has not made it any less painful for households and firms, but it should at least pass relatively quickly. If energy prices stabilise in the new year, the headline rates of European inflation could be back to more normal levels by late 2023.

At the other extreme the US is grappling with domestically generated inflation. Easy monetary policy coupled with a huge fiscal stimulus resulted in an economy running very hot. Core inflation, stripping out energy and food prices, is rising at around 5.9%. Bringing that down will not only be far from painless but also slow. Whilst the Federal Reserve is now tightening policy aggressively, monetary policy changes typically take between 18 and 24 months to fully feed through into the real economy.

Britain sits somewhere in between the two extremes. Energy price inflation is unlikely to peak until early next year – partially because the functioning of the domestic energy price cap means Britain experiences price moves on a lag. But even once energy prices stop contributing to higher inflation, the jobs market looks tight enough to leave inflation running well ahead of the Bank of England’s 2% target: hence the Bank continues tightening even as it predicts a recession. In the Bank’s view the coming downturn is the necessary cost of returning inflation to target in the medium term.

Whilst European inflation will likely peak later than American price rises it should fall faster. An economy which was never quite so hot as its American and British peers will require less effort to cool down. Meanwhile, on both sides of the Atlantic, the Anglo-Saxon economies will require more tough monetary medicine to return their domestically generated inflation to more normal levels. The recession we are in will be painful and prolonged and we must acclimatise ourselves to this eventuality.

COMING UP

25th August, US GDP: Whilst the first estimate of GDP data tends to get the most attention, the second is often more useful. The second estimate of how the US fared in the second quarter of this year is due in late August and will provide a more detailed breakdown – including data on corporate profit levels. That will give a useful indication as to how the pain of a slowing economy is being split between firms and workers. 31st August, China PMI: In more normal times, the ongoing slowdown in the Chinese economy would be dominating the global economic agenda. But with Britain and Europe heading into recession, the US slowing and inflation at 40 year highs this has been pushed out of the headlines. The purchasing manager survey for August is an important datapoint to watch. The central bank – in sharp contrast to its Western peers – cut interest rates this month, analysts will be watching to see if this has revived any signs of confidence amongst firms. 15th September, Bank of England: Having delivered a 0.5% increase at its August meeting the Bank now faces a quandary. Whilst further tightening is almost certain, the Monetary Policy Committee is split as to whether to go for 0.25% or another 0.5%. |