SORBUS spotlight: slowdown

The script for 2022 was not supposed to run like this. After the crisis of the pandemic in 2020 and the lingering lockdowns of 2021, 2022 was supposed to be the year that the global economy roared back to life. Whilst forecasters were rightly worried about a rise in inflation, few foresaw a serious slowdown in economic growth. And yet, especially following the war in Ukraine, the leading indicators are now all flashing serious warning signs.

Across the world high inflation and rising borrowing costs are sapping business confidence and hitting household balance sheets. Disrupted supply chains continue to hamstring production in many sectors and consumers’ appetites for spending are starting to sag. The grim prospect of months of fast price rises, coupled with distinctly soggy growth, appear to lie ahead.

Chinese economic statistics should always be taken with a large pinch of salt. If one believes the official data then growth always appears both surprisingly stable and suspiciously close to the government’s own pre-announced targets.

Private sector data though is now showing a worrying picture. Much of Shanghai – which makes up about 4% of China’s GDP but is the exit terminal for a much higher share of its exports – has been under a severe lockdown for the past six weeks. The authorities have confirmed it will be in place until at least early June. Case numbers have risen sharply in Beijing and other cities, sparking fears of new restrictions to follow.

Locking down major production centres is hardly ideal from an economic point of view.

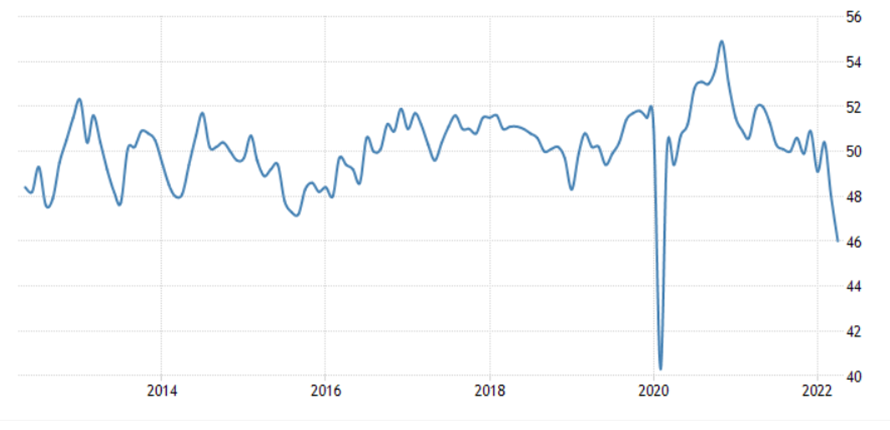

Caixan Manufacturing PMI (China)

The Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) for the manufacturing sector is compiled by asking purchasing managers at firms about the outlook for their own business. A reading under 50 signals a contraction. The most recent data showed the headline reading dipping back into contraction territory.

If China is one motor of the global economy, then the United States is the other.

The release of the GDP data for the first quarter of the year took analysts by surprise by showing an overall fall in economic output. The details, thankfully, were rather more comforting than the headline numbers suggest. The drop was almost entirely the result of a sharp fall in inventory levels rather than because of a change in underlying spending patterns. Ongoing supply chain disruptions probably explain the bulk of it.

But if backward looking data – such as GDP for January to March – were not too grim, the forward-looking numbers are less hopeful. The University of Michigan’s measure of consumer confidence – the longest running and most respected barometer of the mood amongst US households – has fallen sharply as gas prices at the pump have soared.

It is now well below the levels seen in 2020 and giving the kind of readings that are usually associated with recession.

In Britain consumer confidence has also plummeted. GfK’s measure is giving the lowest readings since 2008 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

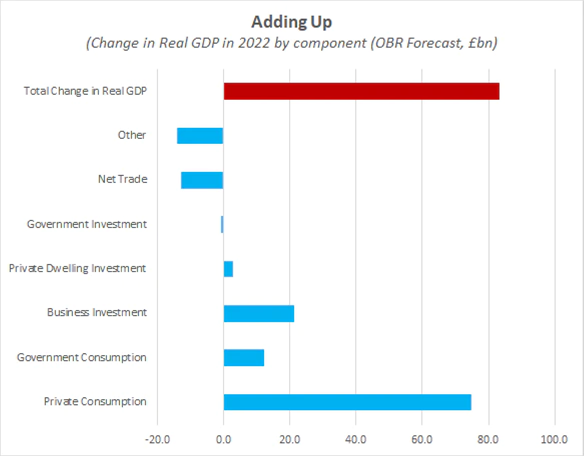

That is especially troubling given that, on the government’s own official forecasts, around 90% of the growth expected this year is supposed to come from consumer spending.

Severely squeezed consumers, buffeted by rising food prices and huge rises in their energy bills, not to mention hikes in their tax bills, may not be prepared to play along.

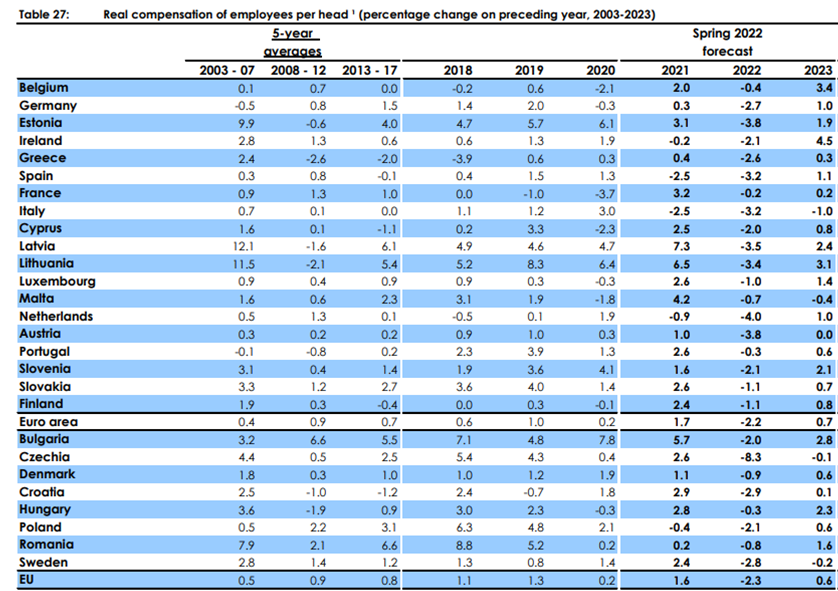

Across Europe the picture is similar. The new forecasts from the European Commission show real wages falling across the Continent this year.

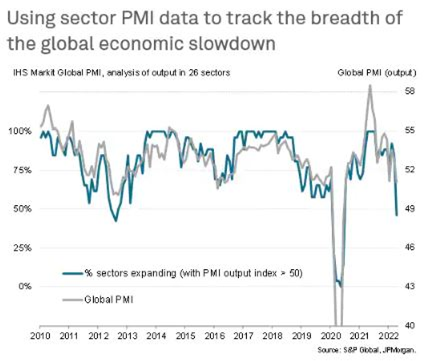

With households increasingly starting to cut back on spending, firms are feeling the pressure. The global PMI index – covering China, the United States, Japan, Australia, India, the largest European economies, Brazil and Argentina – is barely in expansion territory. And the number of sectors reporting expanding turnover has also fallen.

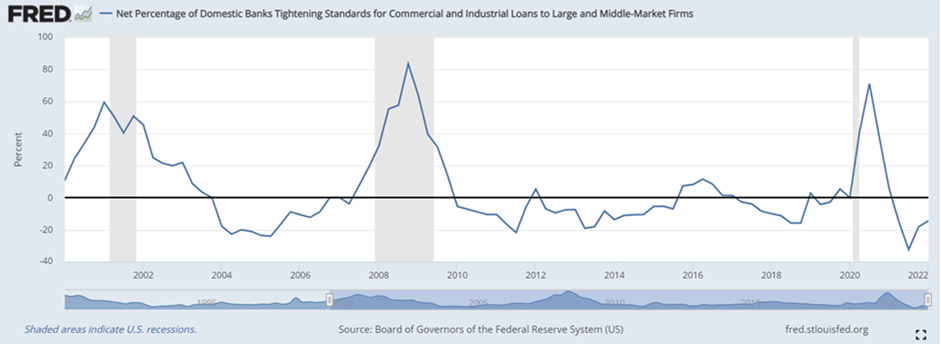

These are usually the sort of readings that one would expect to be accompanied by easier policy from central banks. As growth slows and confidence evaporates, the textbook response is to cut interest rates and try to encourage more spending.

But the major global central banks are doing the opposite. Most are still in the relatively early stages of a tightening cycle that should see rates rise to their highest levels in more than a decade.

Policymakers are trapped between a rock and hard place. Growth may be faltering but inflation remains uncomfortably high.

Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England, repeatedly said at his last press conference that he was treading a ‘narrow path’ between rocketing inflation on the one side and a perilous growth outlook on the other. The language in recent weeks from the US Fed has been similar. They hope to engineer what they term a ‘soft landing’: tightening policy by enough to bring inflation down to lower levels without tipping the economy over the edge into a recession. That is a very tricky balancing act to pull off.

The rising fear is that the kind of rate hikes required to bring inflation back to 2% will be more than already hurting consumers and firms can cope with.

The consensus economic forecasts around the advanced economies continue to see a slowdown in 2022 but no recession. The trouble with consensus economic forecasts is that they have a very poor track record of spotting a recession in advance.

Indeed, British forecasters – as measured by the Treasury’s monthly round-up of private sector forecasts – failed to spot either the 2008-09 recession or the early 1990s one until months after they had begun.

Consumers have a much better intuitive feel for what is actually happening and, over the last thirty years in both Britain and America, consumer confidence has a much better track record of spotting downturns in advance than professional economists.

Right now the best that can be hoped for is a months-long growth scare as the global economy slows sharply from the kind of rates seen in the first quarter. Perhaps things will pick-up towards the end of the year. But if energy prices remain high going into the winter then it is hard to see households having much room to increase discretionary spending. Higher interest rates will not help. The best advice now is to hope for a slowdown and prepare for a downturn.