SORBUS spotlight: the British jobs market: uncomfortably tight

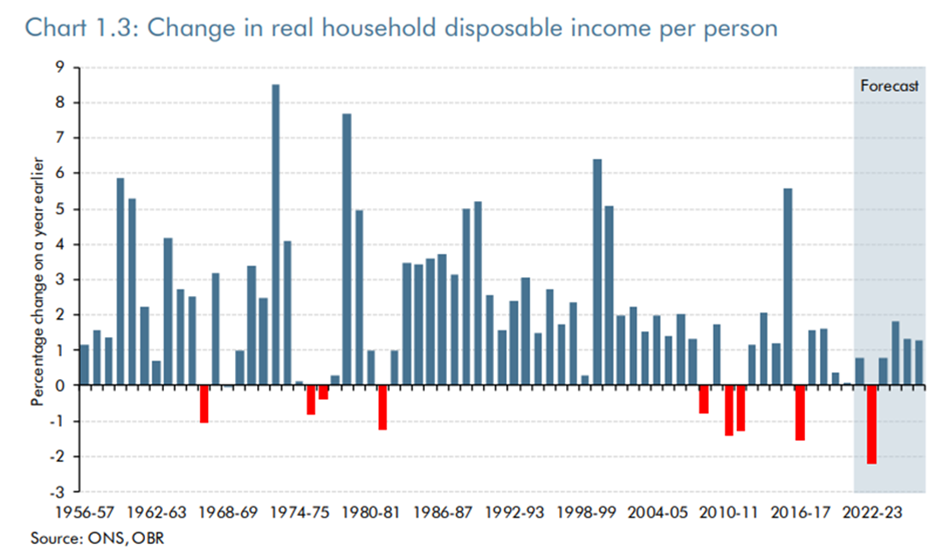

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the arms-length body that provides the government’s official economic forecasts, British households are set for a miserable year. Their real disposable income is forecast to undergo its steepest fall since at least the 1950s.

It’s all a rather far cry from the excited talk last Autumn of a new era of high wage growth supposedly brought in as the pandemic reshaped the labour market.

Getting a handle on exactly what has been happening in Britain’s jobs market and where wages are really heading is far from straight forward.

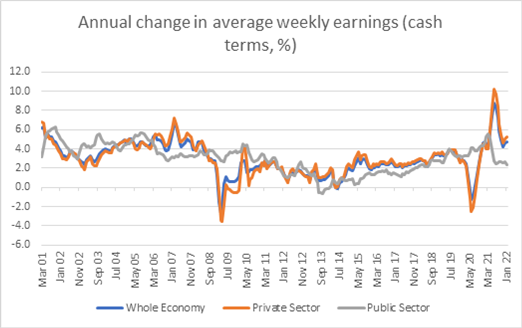

The headline data from the Office for National Statistics suggests that wage growth – especially in the private sector – exploded in mid to late 2021 and that whilst it has recently come off the boil, it is still well ahead of the kind of rates of increase seen before covid-19 hit.

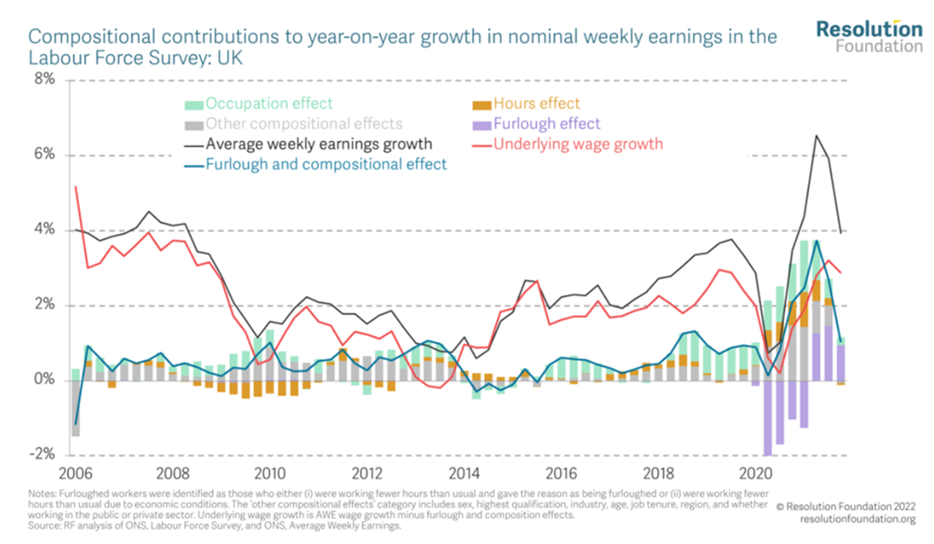

But the ONS are clear that these numbers need especially careful handling. For much of the past two years they have been seriously distorted by what statisticians term base effects and compositional effects.

Private sector wage growth may have been reading over 10% in June last year but a large part of that was because June 2021 was one year after June 2020 – at the height of the economic fallout from the pandemic. That is the base effect.

The compositional effect comes into play because of the nature of the jobs lost over the course of the lockdowns. The lowest paid were the most likely to find themselves out of work. And as they fell out of the sample the average of the remaining workers would have been boosted, even if none of them saw their actual pay increase.

Stripping out these sorts of statistical quirks is neither easy nor straight forward. But doing so is important for anyone trying to get a handle on the outlook for Britain’s economy. With business investment soggy and net trade subtracting from growth, private consumption is forecast to provide around 90% of the additional expenditure that the economy needs to grow in 2022.

The Resolution Foundation, an economic think tank, calculated last week that underlying wage growth was running at around 3%.

That’s well up on the 1.5-2% kind of growth rates seen in the immediate aftermath of the financial crash of 2008-09 but not noticeably higher than in 2019. Although with inflation now materially higher, even 3% means a real-terms pay cut.

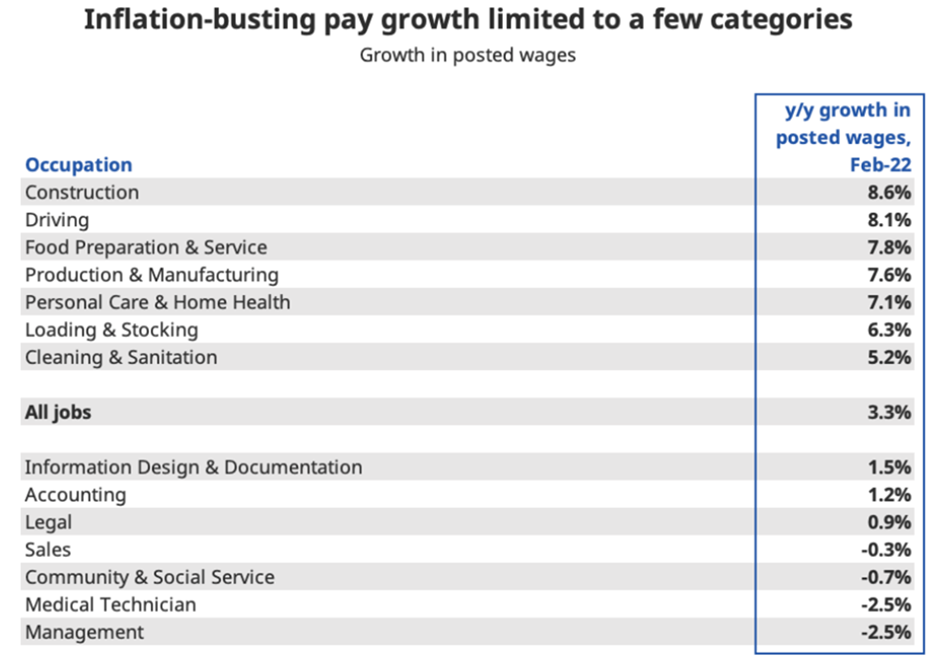

Of course an average hides as much as it illuminates. There is no doubt that some roles are seeing extremely high demand and experiencing faster wage growth. The recruitment website Indeed provides a helpful breakdown of the hot sectors.

The higher wages on offer in jobs such as driving and loading & stocking are consistent with the ongoing switch to online retailing and the growth of the logistics sector. A large increase in the legal wage floor this month, with the National Living Wage rising by 6.6% in cash terms, should put more upward pressure on lower paid roles.

But stepping back, the bigger story is of an increasingly tight jobs market but not in the usual sense. Whilst British GDP has surpassed its pre-pandemic peak, employment levels remain down on where they were in February 2020. Demand for workers has recovered but the supply of labour is now lower; the result is rising wages.

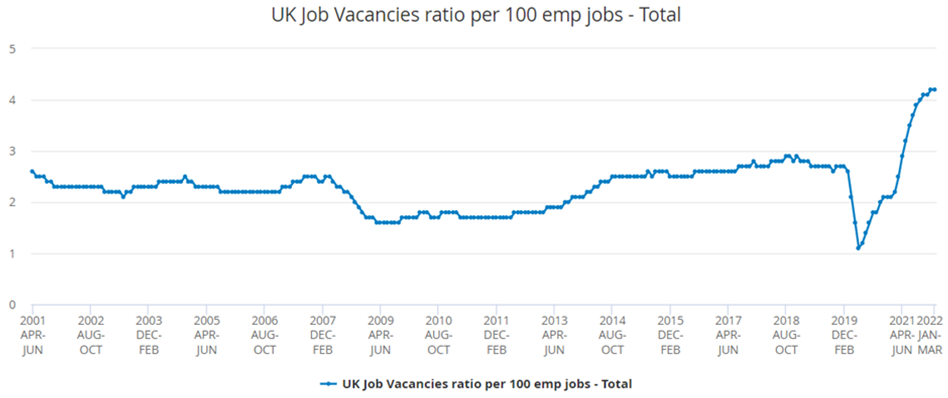

There are now more than 4 job vacancies for every 100 workers employed in Britain. The highest ratio in over 20 years.

Over the course of the pandemic around 200,000 working age people left Britain and whilst some may eventually return, there is so far little evidence of it. But a bigger factor has been British residents becoming economically inactive. Whilst the headline unemployment rate has fallen to just 3.9%, that is more a result of people leaving the labour market than finding work.

Over the last years 486,000 British residents aged between 18 and 64 have slipped into economic inactivity. Just over 226,000 of them, around 45%, report that they are ‘long-sick’ perhaps as a result of the pandemic. Meanwhile the number of students has increased by 164,000.

The change, compared to the pre-pandemic normal, is especially striking amongst those aged 50 to 64 years old. Economic inactivity amongst this age range has increased by two percentage points – representing around 300,000 people. This is the first sustained increase in inactivity from this age group in decades.

This may well reflect lifestyle choices made over the course of the lockdowns. There is evidence that many older workers reassessed their priorities whilst stuck at home and many seem to have brought forward their planned retirements.

Those financially secure enough to have retired in their 50s to early 60s are likely to have been well paid and skilled workers on whom their employers no doubt relied.

The overall picture presented by Britain’s jobs market is not a hopeful one, despite the extremely low unemployment rate. Usually, a tight jobs market is the result of high demand for workers and a sign that the wider economy is in rude health. But the current tightness is as much to do with a poor supply of labour as high demand for it. For firms this is the worst of all possible worlds: the imbalance of supply and demand is pushing up costs whilst the record levels of vacancies suggest that productivity is being harmed by shortages. The unexpected retirement of so many 50 and early-60 somethings is adding to skills shortages. Nor is the supposedly hot jobs market providing much help for workers, with real wages falling even as payroll taxes rise.

The current tightness cannot last forever. Either wages will rise to a level that is high enough to tempt more recently retired workers and immigrants back into the labour force or firms will decide they cannot afford to meet the bill and reduce their own demand for workers. The first scenario would add to inflationary pressures whilst the second would see a renewed rise in unemployment. Neither would be especially good news for the UK macro-outlook.

COMING UPApril 22nd: Global PMI today. The monthly surveys of purchasing managers compiled by Markitt represent the best snapshot of global business conditions. They have a tendency to overshoot on both the upside and the downside, presenting an overtly volatile picture of the health of the economy. Taking them too seriously can lead analysts astray. But they are very useful for spotting turning points in trends. This month’s releases for the UK, US, Eurozone and Japan will provide the first real clues as to how supply chains are handling the fall out form the war in Ukraine.

|