SORBUS spotlight: war, plague and supply chains

Supply chain disruptions are getting worse. Inflation is heading even higher.

On February 18th, as Storm Eunice lashed Britain, the nation’s productivity took a hit. Not so much from the weather, where the damage proved to be contained, but from a previously little-known YouTube channel called Big Jet TV. Up to 250,000 people took time out of their working day to watch a live stream of planes braving the high winds to land at Heathrow, accompanied by excited commentary from Jerry the cameraman. Those watching may have at least gained some insight into the supply chain disruption now hitting the global economy.

The most exciting landings were those of the biggest jets, notably the A380s of Qatar Airways and Emirates. But alongside the big passenger jets came the super-sized freightliners and a surprising amount of them were Russian.

The war in Ukraine is producing a multi-faceted hit to the global economy. Russia may represent less than 3.5% of global GDP – and Ukraine less than 0.5% – but that small overall share in global output is coupled with an outsized role in many markets. The most obvious is energy. Russia produces over ten million barrels of crude a day, making it the world’s second largest exporter after Saudi Arabia. And then there is natural gas, where Russia accounts for around one third of Europe’s usual supplies.

Whilst oil and gas have, generally, been excluded from the sanctions regime so far, their price has spiked as uncertainty over future supply has soared and Western firms have sought to cut ties with the Russian energy sector. Both Shell and BP look set to take large losses on exiting their own involvement.

The energy shock though is just the most visible. An equally serious disruption is occurring in global food markets. Both Russia and Ukraine are traditionally major exporters of grains, sunflower oil related products and the nitrates used in fertiliser production.

Taken together, the increase in the prices of energy and food on wholesale markets seen in the last three weeks could be enough to add two to three percentage points to the inflation in the coming months. But even that understates the extent of the economic shock.

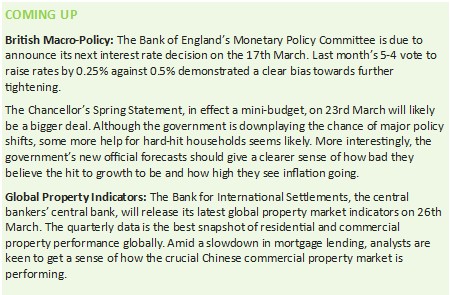

Russia is also a key supplier of several metals, with an especially high market share in palladium, a key input for both automotive catalytic converters and in the aerospace industry. Over the past 12-18 months automotive supply chain shocks have been a major contributor to inflation in both North America and Europe, with a shortage of new cars pushing up the prices of used cars by record amounts.

Supply chain and energy analysts expect a rejigging of global value chains. Europe will likely buy less Russian energy and China more. That should free up gas supplies in Asia to be imported into Europe. But the process will likely be neither quick nor smooth. Rerouting global energy networks will take months rather than weeks and be accompanied by materially higher prices for firms and households.

All of which will have to be accomplished amid a wider disruption to global air freight. The super-heavy air freight market, used to transport especially high value but bulky goods such as jet engines, has long been dominated by Russian and Ukrainian airlines flying heavy planes such as the AN-225, the AN-124 and Ilyushin-76s. These planes have now lost access to European and North American airspace. Russia’s response, of closing its own airspace to European and American flights, will add yet more disruption to general air freight. Avoiding Russian airspace adds something in the region of 6-8% to the flight time and costs of Asian to European airfreight and reduces the available load due to the higher fuel requirements.

The war is being accompanied by soaring energy costs, rising food bills, shortages of key metals and disruption to air freight – all of which will act to reduce growth and raise costs. But the war is not the only supply shock the global economy is faced with.

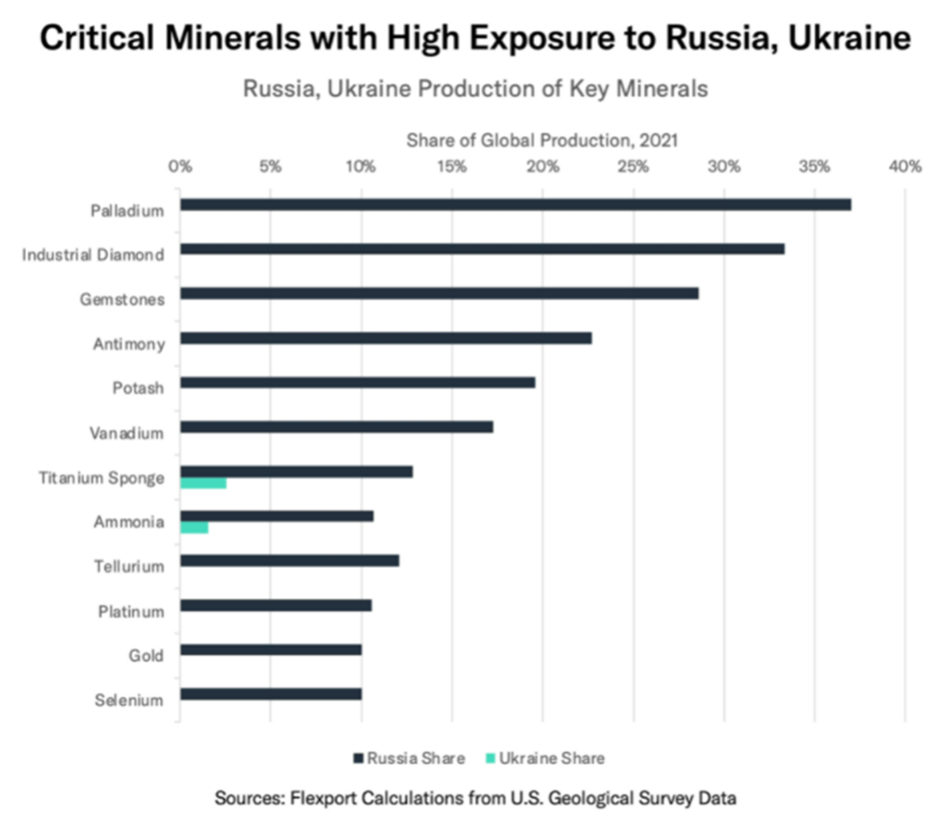

Whilst the media headlines have been dominated by the conflict in eastern Europe, the pandemic is not yet over. The Omicron wave that washed over Europe and North America in December and January is now hitting Asia.

Case numbers are soaring in countries which had previously been seen as having a ‘good pandemic’.

Lower vaccination rates and the reliance on the Chinese made Sinpac vaccine (which is less effective against newer variants) suggest that hospitalisations and the death rate will be higher than Europe and North America experienced.

The human costs will be joined with an economic cost. China, continuing with its zero-covid policy, has already announced a lockdown of Shenzen and Jilin, two of the largest ports in the world, to last for at least a week. Apple’s largest assembly plant in Asia has closed its doors.

The disruption to global manufacturing chains, especially in consumer tech and clothes, looks set to be as bad as in March and April 2020. At present it is unclear how long lockdowns will last, but a reasonable base case is to expect the problems to persist for at least the next six to eight weeks.

2022 began with a sense of quiet optimism about the global economy. The Omicron wave proved manageable in the West; jobs markets looked tight and there was a sense that things were beginning to ‘normalise’. Supply chains were being re-established and both governments and central banks were in the process of turning policy away from its emergency setting of 2020-21. Rising inflation was a problem. But one that central banks thought they knew how to deal with.

The two, near simultaneous, shocks of war in Europe and serious covid outbreak in Asia risk changing the mood. Inflation is simply less manageable than central banks expect and the renewed challenges to global supply chains will begin to hit both output and confidence.

In the UK, the consensus estimate – before the recent shocks – was that inflation would peak at around 8% in the early spring before falling back to closer to 3% by the end of the year. Those estimates are now heading up. A peak over 10% now seems more likely and, perhaps even more troublingly, the data suggests inflation will be well over the forecast 4% by the end of the year. Nobody talks about this being ‘transitory’ anymore. Inflation driven by global shocks is especially tricky for central banks to respond to. In the final analysis the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank will have to accept that even as they tighten policy in the months ahead, firms will see their cost bases rise and households their real income fall.

British households now face, amid rising taxes and rising prices, the steepest fall in their annual real incomes since the 1950s. The big question is whether the large rise in household savings seen over the course of 2020 will now be tapped into to help maintain their spending or whether Britain’s consumer-led recovery from the pandemic is entering its final months.