Election 2015

“The most important election of a generation”

David Cameron

This note examines the above assertion and explores the impact for investors of today’s vote. We make no prediction as to the outcome or the accuracy of the polls: we are merely exploring the consequences of the various scenarios.

The election has been an ill-tempered affair that has taught us very little about either the political parties or their leaders that we did not already know. David Cameron has been feigning a passion and energy we have seldom seen over the last five years and Ed Miliband has been asserting he is tough enough (“Hell yes!”) to be PM despite his prior difficulties overcoming a bacon sandwich. We should be grateful for the small mercy that there was only one debate.

The election campaign has been described as a “carnival of nonsense and futility”. We agree with the latter elements but if this was a “carnival” then can we suggest that as a nation we outsource management to the Brazilians – ours is rubbish.

In policy terms there has been much noise but it appears that there is neither anything particularly new or different from either party. The Labour party would prefer to reduce the deficit over a slightly longer time frame and be more interventionist in markets but their policies are broadly similar to the Conservatives.

As they should be.

As a country we have not managed to balance the books since 2002 and the coffers remain as bare as they were five years ago.

Also the outcome tonight is likely to reveal that neither party has earned a mandate for anything other than a centrist approach. Radicalism requires a majority as well as the intellectual and ideological ambition that neither party appears to possess.

The content of the debate has also been unusually narrow. Politicians have conspicuously avoided discussing foreign affairs, the NHS, housing supply or even Europe. Shamefully the UK press has been complicit in this and the most examining questions faced by politicians have largely been from the general public.

As we vote it appears likely that the Conservatives will win around 280 seats and the Labour Party around 265 seats. This

15 seat victory is easily swamped by the 77 seats the SNP and Lib Dems will probably share (50 and 27 respectively).

As has been obvious for months it’s going to be a coalition again. The difference from five years ago is that the Lib Dems cannot deliver the required votes to supply a majority but the looming menace of the SNP – the outstanding success of this election – can. These votes will never go the Conservative way but for the Labour party they are as much of a poisoned chalice as an opportunity. As the Conservatives are toxic in Scotland the SNP is equally regarded in England.

So if neither party has the desire nor the mandate to drift far from centrist economic policies then we can expect little impact on equity or bond markets. If the coalition were to be “reddish” of hue then there are some sector specific impacts from declared policies:

- Banks and bankers will face an additional taxes in order to pay for a “Compulsory Jobs Guarantee” for the young and unemployed.

- The freeze on gas and electricity prices until 2017 will also impact the utility sector.

- The abolishing of Non-Dom status and other city unfriendly policies may undermine the financial services industry.

However, these impacts are likely to be short term and minor.

We would highlight three areas of importance that flow from today’s election but conclude that they are unlikely to affect markets or investment strategies in any significant way:

- UK’s relationship with Europe.

- Scotland’s relationship to the UK

- Electoral reform

Europe yet again

The Conservatives have promised a referendum on our membership of the EU. As UKIP would be in favour and the Lib Dems have not “red-lined” this then it has a reasonable chance of taking place. A YouGov poll from Tuesday said that 45% would vote for U.K. to remain in the European Union, 33% would vote to leave.

The probable outcome is that the future “blueish” government will claim some important concessions have been wrought from the EU (though they are likely to be vanishingly trivial) and will suggest we vote in favour of remaining inside and this will be the result.

However, the unlikely alternative (a UK exit) would again be less distant from the status quo than the politicians or press would have us believe. We were never in the Euro, and while we complain of an inability to influence EU legislation we would be unable to escape much EU legislation outside the club. Plus ça change.

An exit would of course create uncertainty but the impact is easy to overstate. Sterling is already a haven currency for many, especially Europeans, and this will persist. Our vulnerability to a Greek default is already low but would be further reduced on exit, thought this is admittedly hypothetical. Greece’s fundamental inability and unwillingness to repay its debt is likely to have finally precipitated its default by the time we have a referendum.

In addition many large UK domiciled companies are truly international; think Diageo, Unilever, Rolls Royce, JCB, Jaguar Land-Rover, even Clifford Chance, Linklaters and the Big 4 accountants. Fully 75% of the revenues of the FTSE100 currencies are denominated in currencies other than £.

However, if there is to be any politics inspired volatility it will be located in this area. An increased likelihood of a UK exit will inevitably draw eyes towards those companies that will be directly affected in the short term.

It should also reveal the strange fragility of the EU. Despite deeply established supra-national institutions and legal systems any country’s tenure in the club is conditional on the whim of its electorate. Membership of the EU has for decades been viewed by its political elite as a sine qua non. Extended austerity and deep recessions throughout the periphery of the Eurozone has led to the emergence of political parties that do not share this view that the EU, and especially the Euro, are self-evidently essential.

The UK’s navel gazing over the value and virtue of its EU membership might prove contagious.

Political polarity

England has followed much of Europe towards the fragmentation of once dominant political affiliations. The two main parties have been considerably diminished and fringe parties are gaining traction.

Conversely in Wales and especially Scotland there has been a concentration of political power towards separatist parties. However, as the Scottish referendum revealed, devolution is a process not a point in time.

Power has been flowing from Westminster to Holyrood and this will continue. The strength of the SNP, a party with “nationalist” in its name, suggests that this journey will be quicker and the destination may be formal separation rather than extended devolution. Though the economic and investment consequences look trivial for England; the UK’s international credit-worthiness is founded principally on England and the absence of Scotland would marginally strengthen it.

Electoral reform

Two consecutive elections will have seen the two main parties at stalemate and disproportionate power flow to minor parties. The first-past-the-post system looks unable to adequately reflect the nuance and balance of voter’s intentions.

It will also deliver, in Scotland, nearly 10% of the Westminster seats (with the additional influence they will bring in a coalition) to only 4% of the population. The rising concern with the indefensible Barnett formula and the “West Lothian question” will be amplified by the powerful influence of the SNP on English politics. For a party that desires separation keeping their fingers pressed to these English pressure points is likely to further their cause.

The Conservatives may well regret opposing the Lib Dems Alternative Vote referendum and would certainly find supporting it now a cheap price to pay to secure future Lib Dem support. This is likely to be a post election hot topic especially if the formation of a coalition is drawn out or a weak minority government inches along trying to stay one step in front of a looming “no confidence” vote.

Overall the result of today’s election is a very long way from being of generational importance. Whichever party is elected will end up implementing a series of largely indistinguishable centrist policies.

The election outcome is unlikely to trouble bond or equity markets.

The risks that scare people are seldom the risks that kill people. Today’s election outcomes are in the category of risks that scare people.

Which begs the question of what would move bond or equity markets? What are the risks that kill people?

The risks that kill us

The most direct influencer in the short term is likely to be the European Central Bank’s policy of quantitative easing (QE) which will have a larger impact on the UK economy than proposed government policy. Mainland Europe is our most important trading partner and any increase in aggregate European demand will increase the demand for British exports. The injection of one trillion € into the stagnant European economy will be a major determinant of UK economic growth and bond and equity pricing.

However the West’s aging demographics and falling productivity suggest that global GDP growth will be lower in the future than it was. This alone is an inadequately understood source of market concern but what happens when politicians fail to understand this? Will central banks be led by politicians to continue flooding markets with QE trying to attain levels of growth and inflation that are structurally impossible? What will be the consequence of this misallocation of capital?

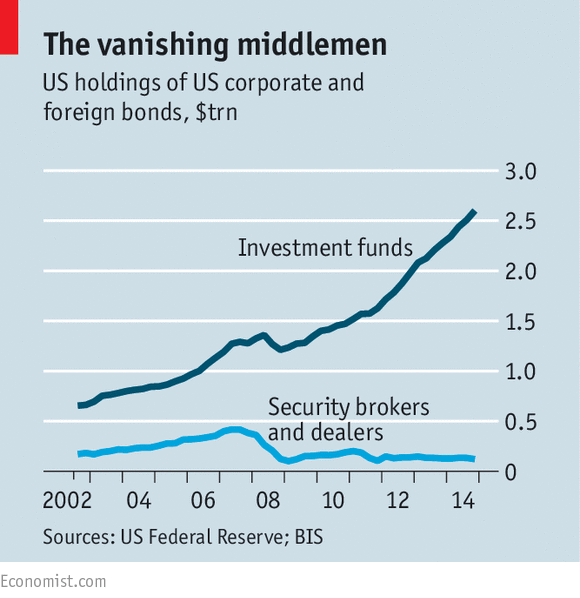

Additionally we remain occupied by some latent structural risks. Liquidity in corporate debt markets is a major concern. By liquidity we are here referring to the capacity of investors to sell their positions at a price close to the market price when there are many other sellers. If liquidity is adequate the seller gets the market rate. If liquidity is inadequate then the seller has to take whatever rate goes when there are no buyers. It was under these conditions that in the depths of the financial crisis forced sellers of a bond that would mature in three months at 100p would find the only buyers at 50p.

As can be seen (below) the massive majority of holders of these debt instruments (unit trusts, OEICs, ETFs) would be in that situation should significant redemptions arise.

SOURCE: US Federal Reserve, BIS, Economist

SOURCE: US Federal Reserve, BIS, Economist

Other latent risks can be found in the unintended consequences of the reams of post-financial-crisis legislation that has emerged. The new Solvency II regulations impose asset allocations on life insurers and pension funds that simply do not serve the best interests of consumers, the financial system or the broader economy. The Dodd-Frank laws attempted to reduce systemic risk by centralising and standardising but we have concerns of the functioning under stress of under-capitalised central counterparties to derivative contracts. A recent technical article’s headline sums it up nicely: “Low yields, weak covenants, narrow spreads and illiquid to boot. What could possibly go wrong?” (SOURCE: MacroStrategy Partnership)

Intensive regulatory interference into markets whose complexity and interconnectedness is poorly understood and widely underestimated means that only those who have unshakable faith in the wisdom and serenity of politicians and regulators should sleep soundly.

In short, investors can legitimately have many things to worry about, but the outcome of today’s election is unlikely to be one of them.

“Let’s face the music and dance”

Irving Berlin