SORBUS spotlight: Tariffs and the dollar.

We have discussed the impact on asset prices of the “Trump tango”, but we wanted to explore the US dollar more closely.

The two words that have cropped up the most so far when analysing the economic impact of Donald Trump’s second term have been ‘uncertainty’ and ‘tariff’. Indeed, the two have often been used together. It is not difficult to see why.

A simple timeline of the new administration’s major tariff announcements so far is instructive, so let’s recap. On February 1st the White House announced that from February 4th, goods entering the US from Mexico and Canada would be subjected to a 25% tariff, whilst those coming from China would be hit by a 10% levy. Two days later, on February 3rd just hours before they were due to go into effect, the tariffs on Mexico and Canada were delayed for a month. On February 10th a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminium imports beginning on March 10th was announced. On March 3rd, to the surprise of many who had expected a further delay, the Canadian and Mexican tariffs took effect. The following day, March 4th, in a further surprise the tariff rate on China was doubled from 10% to 20%.

On March 6th goods compliant with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) – negotiated by the first Trump administration – were excluded from the 25% tariffs. That reduced the proportion of goods being caught in the net by around half. But on March 26th the White House announced a new 25% tariff on all cars and car parts globally, scheduled to begin on April 3rd, which would hit many of the USMCA imports from Canada and Mexico exempted on March 6th.

In April, things moved quickly. On April 2nd the President announced a 10% universal tariff to apply to pretty much all US imports as of April 5th together with a set of so-called ‘reciprocal’ tariffs to come into effect on 9th April. These varied from 20% on the European Union to a staggering 90% on Vietnam. The following day the scheduled car import taxes came into effect although car-parts, which were due to be covered, were exempted until May 3rd.

The 10% universal tariff followed on 5th April and the much higher reciprocal tariffs on 9th April. The tariff on China, following Chinese retaliation, was stepped up to 50% on April 8th.

On April 10th, after a rough reaction from markets, the reciprocal tariffs were all delayed by 90 days with the exception of those on China, which were stepped up – once again – to 125%. Although on April 11th smartphones, laptops and semi-conductors were exempted from the China tariffs. To add to the confusion, these exemptions were described as temporary the following day although no dates were given as to when the exemptions would be ended.

That brief history misses other points, points which matter to a great many small, medium and even large firms. The so-called de minimis exemption, for example, which excludes very low value goods from any form of customs duty has been dropped, brought back into effect and then dropped again. That exemption is crucial to the business model of firms such as Temu and Shein. What is more, separate tariffs have been promised for the following weeks and months covering lumber, copper, pharmaceuticals and semi-conductors. There are though currently no real details on the timeline or levels involved.

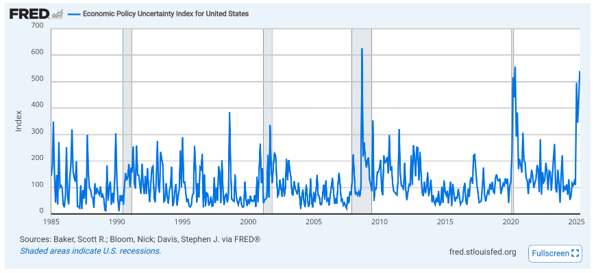

It is then understandable that the word ‘uncertainty’ has been bandied around so much in recent weeks. One measure of policy uncertainty has hit the kind of levels last seen in the pandemic and the financial crisis:

(Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USEPUINDXD)

The economic evidence suggests that elevated levels of uncertainty about future policy do not just make the job of investors trickier and make commentators grumpy; they also do real economic damage. As long as elevated uncertainty lasts, firms tend to delay or pause investment decisions and hiring plans.

Brexit provides a useful analogy. In the longer run, theory suggests that Britain’s decision to leave the European Union will lead to less trade with the EU and that will have an impact on productivity growth that slowly builds up over the years. But the much more immediate economic hit came between mid-2016 and late 2019, before Britain even left the Single Market. For more than three years the future nature of Britain’s trading relationship with Europe remained entirely unclear. The result was delayed investment plans which subtracted from growth in the short term.

But if uncertainty dominated the picture in February and March – and has remained alive and well so far in April – the actual tariffs themselves have been more of an issue in April.

Even after the delay on the reciprocal tariffs the current state of play represents a very high tariff wall. The baseline of 10% covers most imports. Many imports from Canada and Mexico together with steel, aluminium and cars are subjected to 25%. Most imports from China are being charged well over 100%.

The average US tariff level in 2024 was 2.5%. The average tariff now is something between 20% and 25%. Working on the average is tricky as presumably the share of imports from China is set to drop sharply in the weeks and months ahead.

The administration hopes this will, ultimately, lead to more production returning to the United States but such moves, if they ever do occur, will clearly take time. Complex supply chains in the automotive sector and modern electronics cannot be reconstructed in a matter of months. Then there are goods such as, say, bananas or coffee which the United States would struggle to produce domestically in any case and are now subject to import taxes.

More broadly one can question if there is really any upside to the United States in even trying to reshore the production of items such as trainers or T-shirts. Most of these items sold in the US are currently imported from either China, Vietnam or Bangladesh where wages are notably lower. Such manufacturing is fairly low tech and not especially productive. Would redeploying American workers to T-shirt and trainer manufacturing really be a net good for the economy?

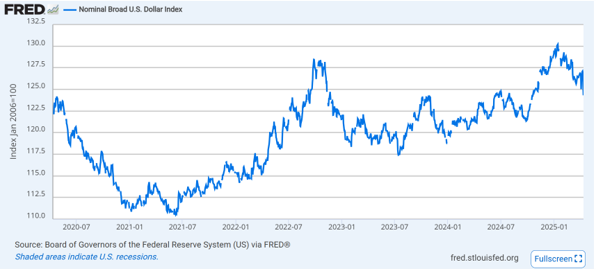

In the days following the major tariff announcement on April 2nd, stock markets were rough and US government bonds fell in value, as discussed in previous notes. But more interesting, from an economic point of view, was the behaviour of the dollar.

A stronger dollar was a near uniform forecast going into 2025. President Trump’s policy combination of tax cuts and deregulation would, it was assumed, raise the yield on US government debt – making dollars more attractive – and increase US economic growth. Together that would send the greenback higher.

Tariffs added to this argument. The theory was that tariffs would help close the US trade gap, meaning fewer dollars left the country and further increasing their value. What is more, many countries hit by tariffs would allow their currency to depreciate to offset the impact. This theory was backed up by solid evidence, this is broadly the pattern that followed the first Trump term’s actions on tariffs.

But so far at least, this time around the theory was proved wanting.

(Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DTWEXBGS)

The dollar has weakened rather than strengthened as tariffs have been enacted or threatened.

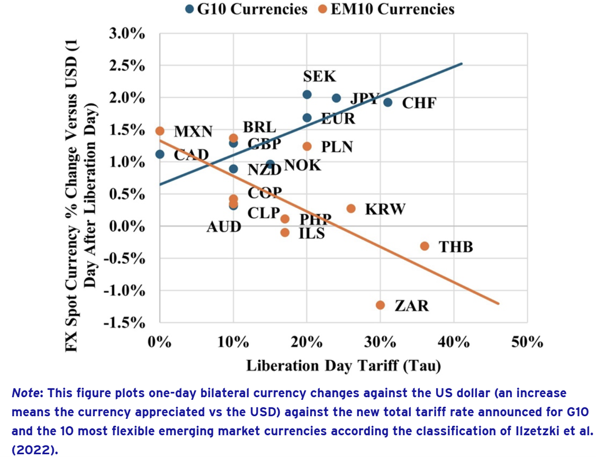

Interestingly there appears to be a divergence between the value of the dollar against other developed countries and emerging economies.

A few possible culprits have been identified for this move. The most likely is that US tariffs are now so wide ranging they are expected to have a significant impact on US equity returns and investors, especially foreign ones, have been reducing exposure to the US stock market and topping other holdings. That is helping to drag the dollar lower.

A more worrying theory, floated in the early part of April, was that this represented a loss of faith in the dollar as a safe haven. It was notable that for several days US stocks, US bonds and the dollar fell in unison – an unusual combination.

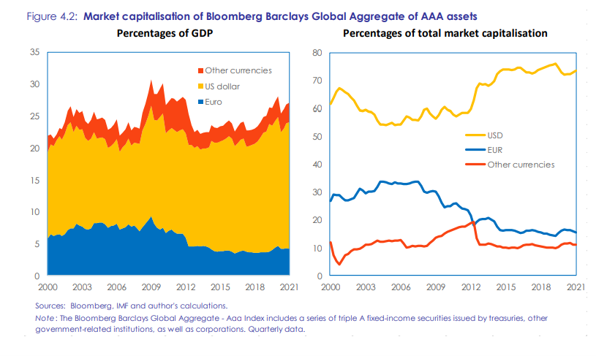

But fears of the reserve, safe haven status of the dollar will likely remain fears rather than reality given the lack of a plausible alternative. Even Germany’s about turn on borrowing is not enough to supply the market with enough safe paper to replace the greenback.

Perhaps higher German issuance and growing concerns over US stability might lead to new flows into reserves gradually diversifying away from North America, but it will take a long time for the role of the dollar to be seriously diminished.

In the short term though, dollar weakness is a real problem for the United States. Almost every forecast of the impact of tariffs on the US economy and US prices, assumed some dollar appreciation which would offset the rising price of imports. If the dollar is down, or even flat, the impact on prices will be higher than expected. CPI inflation heading north of 4%, or even 5%, in the next 12 months no longer looks unrealistic.

This then is the primary issue: the hope was that President Trump’s push on deregulation and tax cuts would boost US growth, whilst tariffs would be a small and manageable drag. But the focus on tariffs, their unpredictability and the fact they have been imposed at much higher levels than expected means they have crowded out everything else in the short term.

Rather than revising their estimates of US growth upwards, analysts have been cutting their forecasts. The dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency is probably safe for now. But the US economy looks to be heading into a rough patch.

|

What we are watching German GDP, 30th April – Germany’s two year long recession has likely finally ended but growth probably began the year on a weak footing. The new government’s decision to borrow one trillion euros over the coming decade for infrastructure and defence spending may help revive growth. But much will depend on how quickly the cash can be deployed. US PCE Inflation, 30th April – The Fed’s preferred gauge of price pressures is worth watching closely. The data for March will be too early to see much tariff impact, but that should begin to hit the numbers from April. the Fed, 7th May – The Fed finds itself in an acute position. Higher price pressures guard against cutting faster but weaker growth calls for easing. At the press conference Chairman Powell will likely try to steer a middle course and not commit future policy until more data is available. |