SORBUS spotlight: The UK’s Fiscal Mess

Last Autumn, at her first budget, Rachel Reeves took a gamble. It has not paid off. At her first fiscal event the Chancellor went big: annual government spending received a £70bn increase with around half of that funded by rises in taxation (with the burden disproportionately falling on “business”, though of course this is in reality a tax on people) and half by increased borrowing. The government hoped to front load the pain of tax rises into the first budget of the Parliament; the messaging was very much that this was a ‘one and done’ tax increase rather than the beginning of a process.

We disagreed at the time “This budget is the start of a tax raising process, not the end of it.” [SORBUS 5th Nov 2024 “Budget reflections”]

The Chancellor left herself with just £9.9bn of ‘headroom’ to meet her target to balance the current budget (i.e. excluding capital spending) by 2029/30. In fiscal terms, £9.9bn does not amount to very much. Indeed the average wiggle-room against their fiscal rules which Chancellors have left themselves with over the last fifteen or so years has been closer to £25bn. The gamble then was that the economy would perform roughly as well as forecast and hopefully even surprise to the upside. As things improved so too would the forecast amount of headroom, perhaps even giving space for more generous budgets in the future.

The world though has not followed the script. It has only been five months since the last fiscal event, but things have gotten off track. Growth in Britain has been through a soggy patch. Whilst the hit to business confidence associated with the larger than expected tax rises announced at the budget will have played a part in that, the bigger story has been generally weak growth in Europe and rising gas prices. The election of Donald Trump has increased global uncertainty, exasperating the hit.

The Office for Budget Responsibility slashed their forecast for 2025 growth, down to just 1% but, rather optimistically, revised up subsequent years. Taking the OBR numbers at face value, they simply assume that any absent growth from the last few months will eventually show up in the future.

That is unlikely: the OBR is now notably more optimistic than the Bank of England or the bulk of independent forecasters.

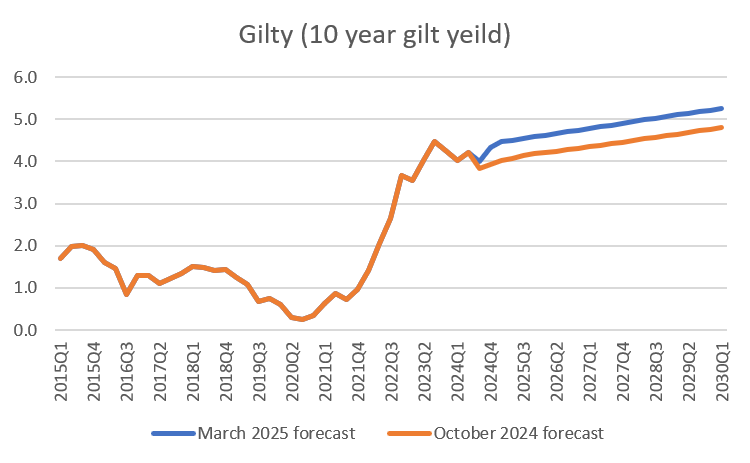

Nor was slower than hoped for growth Rachel Reeves’ only source of problems. The yield on gilts (British government debt) has risen faster than expected. Once again, much of that upwards move reflects global factors – rising yields on US Treasury bonds, which have a magnetic-pull on gilts. The rise in US Treasury bonds is driven by the likelihood that President Trump will further increase US borrowing, stoking inflation in the US.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (data as at: 27/03/25)

Once again, there are real fears that the OBR’s new forecasts may prove too hopeful. Their forecasts for gilt prices in the coming years are based on the futures market as it stood towards the end of February. Since then yields have taken another small leg up.

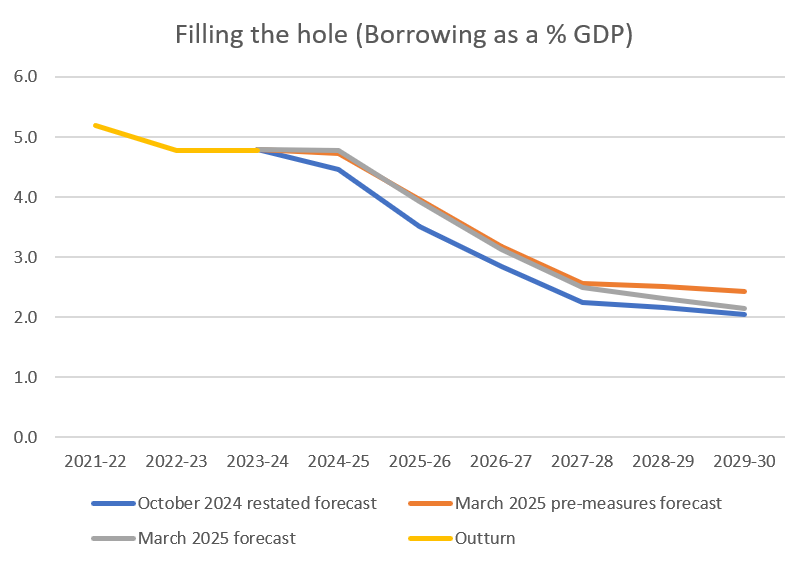

Whatever the balance of global and national factors, the end result was that the Office of Budget Responsibility calculated that (before taking into account any new policy measures) the £9.9bn of headroom for 2029/30 forecast in October had slumped to a deficit of £4.1bn.

The Spring Statement was supposed to be just that; a statement, a chance for the Chancellor to issue updated OBR forecasts rather than to set out new policies. Indeed, the government has made rather a large fuss about moving to once a year Budgets and not fine-tuning fiscal policy for the sake of it. But with the newly imposed fiscal rules now set to be missed, the Chancellor engaged in rather a lot of fine-tuning. After her policy changes, the headroom was restored to £9.9bn. It goes without saying that there is nothing special about that number. But, it does look like a great deal of the policy agenda was to signal that there has been no slippage.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (data as at: 27/03/25)

The chart above displays the figures as a share of GDP. It shows the old forecast, the new forecast before taking into account any policy changes (pre-measures) and the final published forecast after the Chancellor made her tweaks.

The tweaks have returned the 2029/30 position roughly to its previous starting point, although the path to getting there is at a slightly slower pace, implying a cumulatively higher borrowing over the course of 2025, 2026, 2027 and 2028.

With the Chancellor reluctant to raise taxes outside of the annual budget and adamant that her fiscal rules were not up for debate, that left just spending cuts as an answer. The necessary cash has been cobbled together through a combination of welfare cuts and a promised tighter package for government spending outside of health, education and defence. The Chancellor’s rules do allow for more flexibility on capital spending, so alongside the pain came some small measures to boost government investment.

In reality cuts to planned public spending and welfare amounting to around 0.4% of national income over five years are not a big deal in macroeconomic terms. And whilst they may cause some political ructions they are unlikely to materially affect growth.

The Chancellor mostly left tax alone at this statement, other than a further planned crackdown on avoidance, something which has become almost a ritual occurrence at fiscal events.

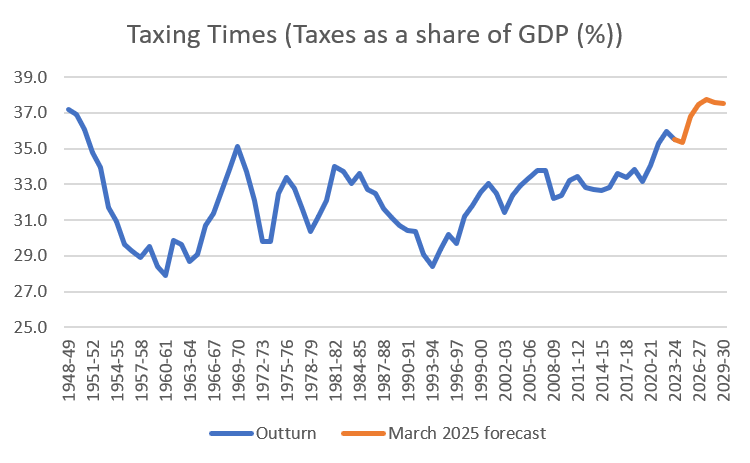

The broad picture though, as regards tax, remains clear.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (data as at: 27/03/25)

Based on the OBR forecasts the tax take, as a share of national income, is set to rise to its highest levels since the 1940s and stay elevated throughout the late 2020s.

The worry now is that the gamble is not over. The £9.9bn of headroom remains rather small and there are at least three clear and obvious risks to the forecast, risks that the OBR made clear exist.

The first relates, once again, to President Trump. Next week he will set out the shape of the next round of US tariffs. And whilst the UK might yet be able to avoid being targeted directly, it is unlikely to be spared the wider economic fallout of more pressure on its trading partners. In other words, the growth forecasts may well be downgraded again.

Within hours of the Chancellor finishing her statement the President had already announced a new round of 25% auto tariffs which the UK will not escape.

Secondly, whilst the government has spelled out a strategy for raising defence spending from 2.3% of GDP to 2.5%, very few analysts believe this is the end point. NATO partners are already seriously discussing numbers in the 3-4% range. Any extra spending on defence means reopening the spending discussion.

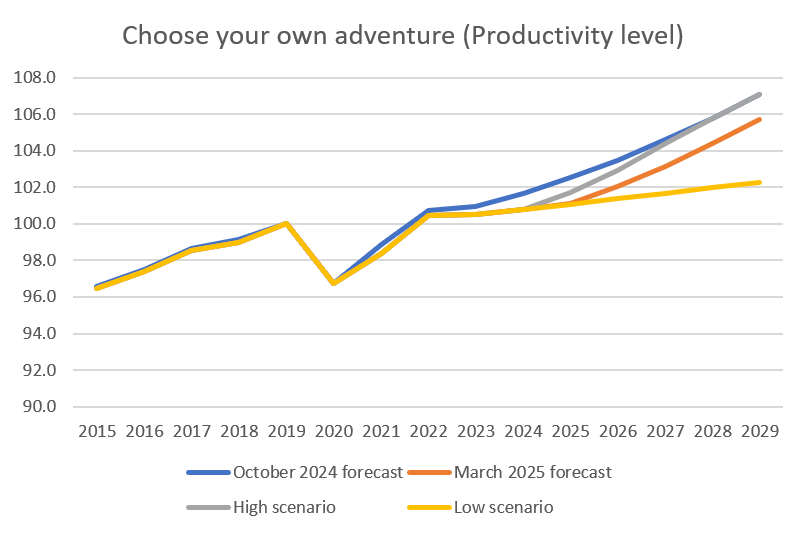

Finally there is a broader risk. In recent years UK productivity growth numbers, the ultimate driver of GDP, have gone from bad to worse. The OBR was clear that it is assuming that around one third of the recent weakness in British growth reflects long term structural factors and two thirds is merely cyclical and will eventually pass. But it reserves the right to change this view if the weakness continues. A further downgrade in medium term growth projections would once again up the fiscal pressure. Overall, the OBR reckons that there is currently just a 50/50 chance of the fiscal rules being met.

The OBR helpfully set out its forecasts for productivity growth alongside some scenarios.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (data as at: 27/03/25)

The ‘low scenario’ is worth taking seriously, if nothing else it simply represents the trajectory of the last few years continuing.

The scale of the challenge can be seen in how the Chancellor went to great lengths in the statement to hail the contribution of the government’s planning reforms to economic growth. Much political capital spending has been expended in an effort to free up the planning system to allow faster building of homes and infrastructure. The removal, in many cases, of the veto for local residents and councils on development is proving politically contentious. The OBR reckon that such reforms will boost the size of the economy by 0.2% by 2029 and by 0.4% by the mid-2030s. That represents the largest improvement to growth prospects that any policy (which does not directly cost the Treasury money) has ever been scored. On the one hand, this is an obvious policy success. But on the other, 0.4% over a decade is hardly game-changing stuff. And if productivity is slowing for structural reasons – such as an aging population, less international trade and others – then many other such measures will have to be found just to stand still.

The worry now then is that the Spring Statement was just the rehearsal for the next budget in the Autumn. Unless the outlook improves in the coming months then the ‘one and done’ tax raises of last year will, as expected, be the start of a process. The base case now should be further downward growth revisions and tax rises this Autumn.

|

What we are watching US Jobs Market, April 3rd – The Jobs market figures for the US remain the most important data for the Fed as it ponders its next steps on rates. US administration figures have pointed out in recent weeks that around 75% of job creation in 2023 and 2024 came from government or government adjacent sectors such as health and education and have acknowledged that the planned rebalancing of growth towards the private sector may cause some short-term turbulence. The figures for February, released in April, may contain the first wave of Federal job cuts. Eurozone Retail Sales, April 7th – European real wages have been growing for 12 months but so far that has not shown up in consumption, instead households have increased their savings rates. ECB policymakers are cautiously hoping that eventually real income gains will show up in spending. Retail sales are worth watching closely. Chinese Consumer Prices, April 10th – Chinese consumer prices are falling. With global trade tensions (with the EU as much as the USA) on the rise, the export safety valve usually used to export excess capacity is beginning to close. Unless domestic consumption picks up, prices may continue falling for the coming months. |