SORBUS spotlight: European growth

Last Autumn Isabel Schnabel, a member of the European Central Bank’s rate-setting executive committee, made a speech simply entitled “escaping stagnation”. The very fact that a rate-setter felt the need to make such a speech is, in of itself, notable. But the content of the address too was worth paying attention to.

Schnabel, a German herself, made the speech in Germany and did not pull her punches. She opened by simply noting that:

The euro area economy is stagnating. Over the past two years, real GDP has expanded, on average, by only 0.1% per quarter. Surveys among firms indicate that growth is likely to remain subdued during the second half of this year.

Almost six months on, that is still true. Indeed, growth in the fourth quarter of 2024 came in at zero percent which Eurostat, the official statistics body, politely chose to headline as “stability” rather than “stagnation”.

But Schnabel, against a backdrop of a poorly performing Eurozone economy, was keen to point out that the economic picture was not uniformly grim.

As she argued:

If one were to plot growth in the euro area excluding Germany, for example, activity in the currency area would have been remarkably resilient in the face of the sharpest monetary policy tightening in decades and a war raging at the EU’s doorstep. Only a few advanced economies, most notably the United States, have expanded at a faster pace during this period.

The problem of course, if that talking about the Eurozone excluding Germany is rather like talking about the United States excluding Texas and California, perhaps interesting but also almost meaningless.

The broad picture though is true.

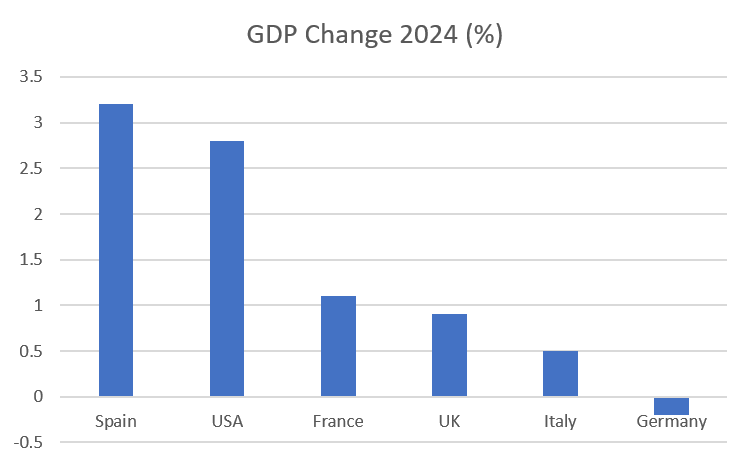

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, IMF (data as at: 26/02/2025)

Growth in 2024, and since the pandemic, has diverged. Germany, and to an extent Austria, the Netherlands and Finland, have experienced weakness whilst Spain, together with Greece, Portugal and Ireland, have raced ahead.

Ms Schnabel’s German audience cannot have enjoyed her references to “the dynamic region” of the Eurozone, which is mostly to be found in the continent’s south. And one can only imagine how anyone in, say, 2013 or 2014, would have reacted to being told that in a decade’s time Germany would be widely castigated as the sick man of the Eurozone whilst Spain, Greece and Portugal were heralded by central bankers and investors as the dynamic drivers of European growth.

Before delving deeper into the tale of two economies that is Germany and Spain it is worth stepping back to look at the longer term picture.

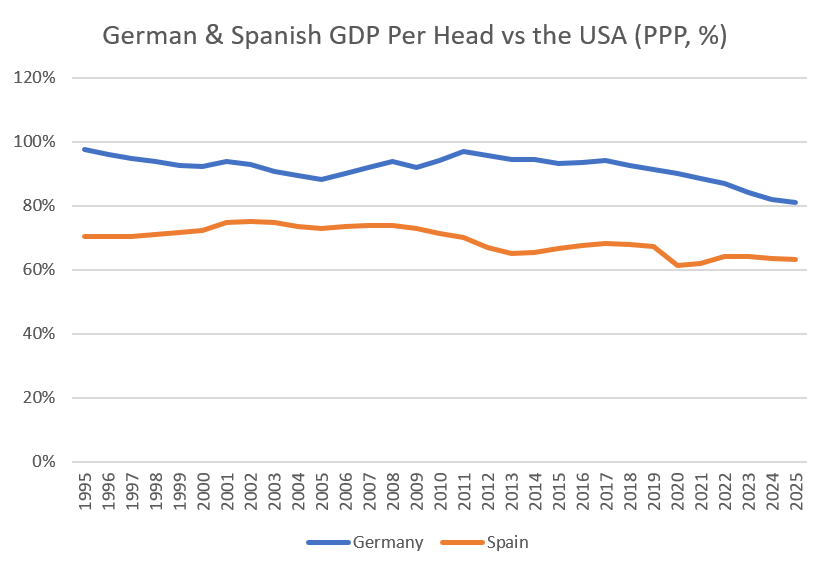

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, IMF, World Economic Outlook Database (data as at: 26/02/2025)

The chart above shows German and Spanish GDP per head, measured on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis relative to the United States since 1995. It should be kept in mind that a flat lining on this graph simply means keeping pace with the United States which has generally experienced the fastest growth of any large advanced economy.

PPP is an attempt to compare like for like, adjusting the figures for the respective costs of goods and services across borders. Whilst the numbers are always somewhat imprecise they tend to give a clearer picture of relative living standards than just using market exchange rates. One needs to be somewhat careful but they at least give a decent indication of trends.

Since the pandemic Spanish GDP per head, on a PPP basis, has kept pace with the growth of the United States, whilst German national income per head has fallen. Despite this though, German GDP per head remains comfortably, for the moment at least, above Spanish levels.

Indeed, the strong performance of Spain in recent years should not obscure that the country remains poorer – relative to the United States – than it was 20 years ago before the global financial crisis.

It is perhaps best to begin by asking what has gone wrong in Germany before considering what has gone well in Spain.

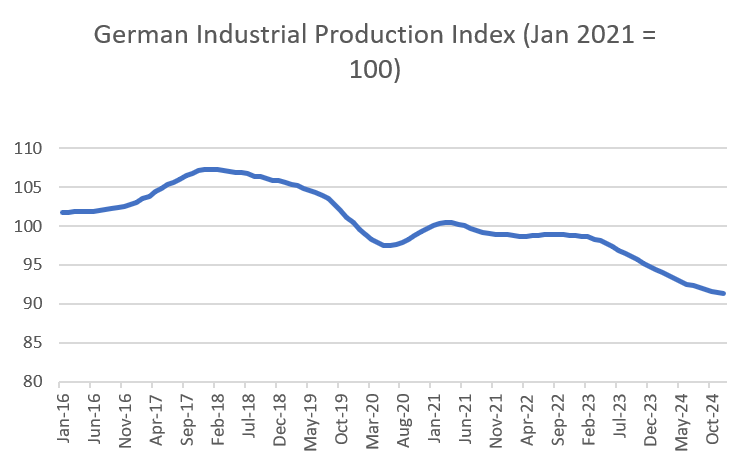

Much of the answer can be seen in a simple chart.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, Destatis (data as at: 26/02/2025)

The last few years have been tough for German industry and in Germany, where manufacturing is more than 20% – more than twice as high as in most advanced economies, this is especially painful.

Indeed it is hard to imagine a set of geopolitical and global macroeconomic circumstances tougher for the manufacturing heavy and export-dependent German economy than have occurred since 2021.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine not only led to a large spike in energy prices but also directly cut off a major export market.

More significant though has been a major shift in Germany’s economic relationship with China. From the early 2000s until the late 2010s that relationship was well-balanced. Germany exported high end manufactured products such as automobiles, advanced chemicals and capital equipment to China and imported, in return, consumer electronics and lower value consumer goods. But China has moved up the value chain. And a domestic slowdown has seen the government look to prop up growth by supporting more exports.

Cars are probably the most totemic example of the new world in which Deutschland AG finds itself. A decade ago Germany exported around four million vehicles annually and China just a million. In 2023 Germany’s exports ran at around two million and Chinese almost three million. In the space of a decade China has transformed from one of Germany’s biggest customers to one of its most serious competitors.

The prospect of new US tariffs has added to the general sense of gloom.

It is important though to note that the general German malaise stretches beyond manufacturing. Whilst manufacturing is around one fifth of Germany’s output, private consumption remains vitally important. And here, despite two years of rising real wages and falling interest rates, savings rates have remained high and spending tepid.

To this can be added a serious demographic crunch. The International Monetary Fund reckon that Germany will experience a fall in the working age population over the coming five years as immigration drops and the population ages.

Whilst Germany has stagnated, Spain has thrived. Four broad factors can help explain this. The first is perhaps pure luck. Spain is less reliant on manufacturing and manufactured exports than Germany and so has been less buffeted by the changing international environment. It is also a sunny destination for tourists which, much like Greece and Portugal, has benefited from the sharp rebound in global travel since 2022.

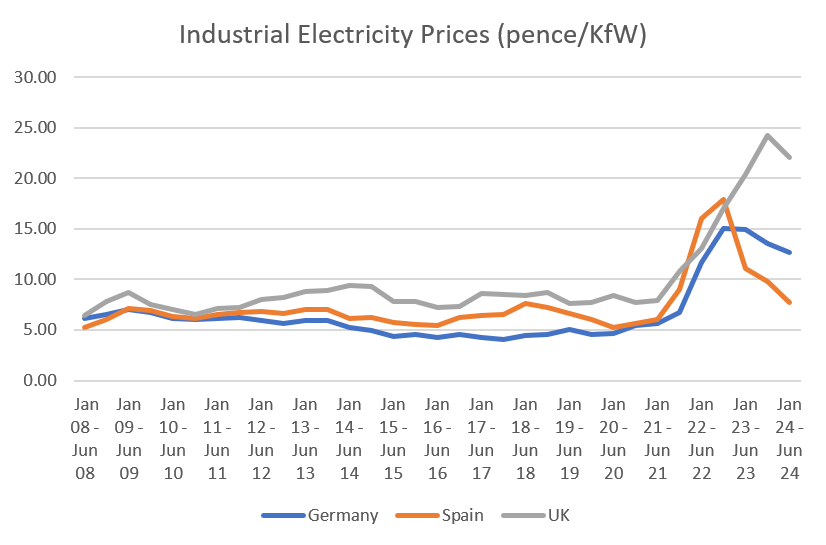

But luck and sectoral mixes are not the whole story. German and Spanish energy costs – especially for industrial users of electricity – have diverged sharply in recent years.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, Eurostat (data as at: 26/02/2025)

Germany, after its ill-fate decision to shut down its nuclear plants in the 2010s, was especially exposed to Russian natural gas and suffered heavily from the energy price spike. Spain, by contrast, is more reliant on renewables.

Those lower energy costs have helped cushion manufacturing in recent years.

It is, as an aside, notable that the energy costs which have hamstrung German industry are still materially lower than those British users are forced to deal with.

Spain though is also reaping the benefits of earlier reforms. At the turn of the millennium, Germany was – much like now – derided as Europe’s sick man. The costs of reunification had been high and the economy was seen as less competitive than its European peers. Beginning in the early 2000s it underwent a period of structural reform – freeing up labour and product markets and holding wage costs down. Competitiveness was restored and German exports to the rest of the Eurozone soared.

In 2012, when Spain, Greece, Portugal, Italy and Ireland found themselves receiving bailouts from their northern European neighbours the price extracted was structural reforms of their own. Meanwhile German wages began to rise at a reasonable clip from 2015 onwards.

A decade later that hard won German competitive edge has been eroded away. The reformed Spanish – and Greek – economies have been better able to cope with the post-pandemic world and have avoided the kind of wage-price spirals found elsewhere.

Finally Spain’s demographic picture looks rather different both to a generally younger population and to much higher levels of immigration. Germany has experienced a wave of migration since 2016 – powered by Syrian and then Ukrainian refugees. But Spain has, rather than accepting those fleeing war, been actively seeking economic migrants to replenish its jobs market. Many have come from Spanish speaking Latin America countries seeking higher European wages. The share of the population born abroad rose from around 5% in 2000 to 18% in 2023. And whilst the wages on offer have been higher than those available in Venezuela or Argentina, they have generally been low by Spanish standards.

Spain’s solid growth looks set to continue. But can Germany turn itself around? In theory higher real earnings and lower interest rates should translate into higher household spending, eventually. But that has been the case for at least the last two years.

Perhaps some optimism can be found in the darkest of circumstances. The new government is already talking up spending an additional €200bn on defence over the coming five years. It may be that a deficit funded military build-up can give German manufacturing the kickstart it needs. Although whether or not that will be enough to counteract the impact of a global trade war remains to be seen.

|

What we are watching Global PMIs, 3rd March – The purchasing managers surveys for manufacturing in North America, Europe and China for February should be especially interesting. The tariff threats (mostly not yet followed through) of the new US government rattled global markets in February, but have they had any actual impact on production and order books? British Services PMI, 5th March – Britain’s economy has lost momentum. The service sector PMI for February will be the last major timely health check before the Chancellor delivers her March statement. Spring Statement, 26th March – At the end of the month Rachel Reeves will deliver her second ‘fiscal event’. The new forecasts have a high chance of showing her missing her fiscal rules. Will the rules change or will taxes rise or spending be cut? The next edition of Spotlight will take a deep dive into the new numbers. |