SORBUS spotlight: There and back again.

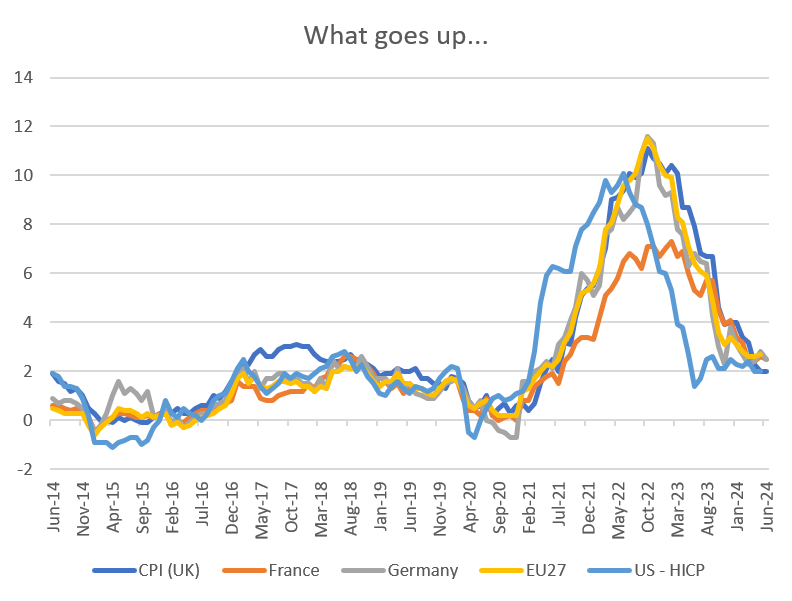

Let’s start with the good news. British inflation in June, as measured by the consumer price index, grew at an annual pace of 2%. That follows the 2% outturn in May and represents the Bank of England (BOE) hitting its target for the first time in many years. Still, given that inflation was above target every month from August 2021 until April 2024 it is probably too early for there to be much back slapping in Threadneedle Street.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, ONS

As Spotlight has noted over the past few years of high inflation, global price dynamics have been very synchronized since the pandemic, with the United States being a few months ahead of the cycle and Britain broadly in line with the European trend. France is a partial exception, inflation there never reached the heights seen in the rest of Western Europe. This is mainly a result of a lower energy price spike, as the French dependence on domestically generated nuclear power proved something of a boon as oil and gas prices spiked.

Another reason that central bankers are not yet ready to congratulate themselves for finally hitting their target is a keen awareness that much of the fall seen over the course of the year to date reflects factors outside of their control. Just as they were not entirely reasonable for the rapid rise in prices after 2020, nor were they entirely reasonable for the cooling.

Broadly put, the story of 2020-2023 was a tale of three factors. There was of course the pandemic and its lockdowns. That seriously disrupted global supply chains for goods at exactly the same time that consumer demand for goods spiked as households were prevented, in many countries, from purchasing services. With pubs, hairdressers and cinemas closed households spending on goods as a share of total spending rose to its highest levels since the 1970s. That unexpected surge in demand for, for want of a better term, “stuff” would always have been a logistical challenge to meet. When coupled with production issues and tricky cross-border shipping, it was doubly disruptive.

Alongside the pandemic stretching of supply chains and reshaping of demand patterns was the largest energy price shock to the global economy since the 1970s. That began in 2021 as global economic activity rebounded faster than global energy output but was supercharged by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

There was not much central bankers could do about those factors. They do not set the foreign policy of the Kremlin and neither do they decide public health policy. The third factor though was more in their control. Monetary (and fiscal) policy was left too loose into 2021 and 2022. The initial lockdowns of Spring 2020 were accompanied by a shock and awe macro-policy response. Rates were slashed, quantitative easing stepped up, taxes cut, government spending increased and soft government backed loans were made available in pretty much every major economy. That prevented a nasty fall in economic output from turning into a new depression. But the policy was not tightened fast enough as economic activity recovered. The result was ultra-tight jobs markets leading to faster wage growth and ultimately domestically generated inflationary pressure.

The story of the last two and half years has been of that policy response unwinding, monetary policy tightening and inflation falling.

British inflation hitting 2% though does not signify that the job is done.

Much of the fall in headline inflation reflects global supply chains finally righting themselves, consumer demand moving back to a more normal pattern and global energy prices coming down rather than a material fall in domestically generated price pressures.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, ONS

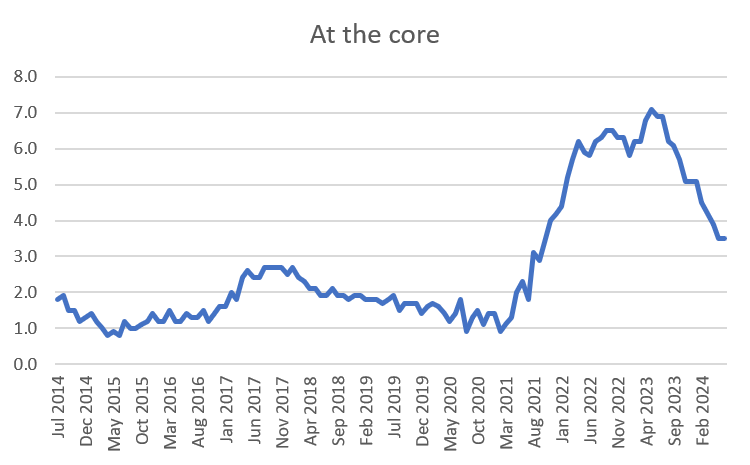

One measure the BOE prefers to look at is so-called core inflation. This is calculated by looking at price changes excluding food, energy, tobacco and alcohol prices. Whilst many non-economists might understandably question the value of a cost of living measure that excludes food and heating, this measure has many advantages from a policy maker’s point of view.

Tobacco and alcohol are a relatively small component of overall inflation and their prices are often dictated by tax changes rather than economic fundamentals.

Food and energy are much larger components but both tend to be more volatile and, crucially, to be most driven by factors set at the global level.

Stripping them out of the numbers provides a data series which is not only less prone to wild swings but also, to an extent, better reflects the kind of inflation over which the BOE should be able to exercise more control.

Core inflation is less driven by Russian foreign policy or developments in global markets and tells policymakers interesting information about the state of the domestic economy. In general central bankers are prepared to “look through”, as they put it, periods of inflation being above target, if core inflation remains – to use another favourite central banking phrase – “anchored”.

That approach makes perfect sense. If inflation rises to 8-10% purely because global energy prices have doubled then it is hard to see what good raising interest rates would do. It would not impact on the direct causes of inflation and would instead simply depress economic activity further.

The reason the BOE, and other central banks, began to hike – belatedly – was because core inflation was not well anchored. They feared that even if energy prices were to return to more normal levels, there were other factors in play.

This is where the news becomes less welcome. Headline inflation may have been 2% for two months on the trot but core inflation remains uncomfortably high.

An inflation rate of 3.5%, on the latest reading, is substantial progress on the 7.1% peak of last May but in recent months progress seems to have levelled off.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, ONS

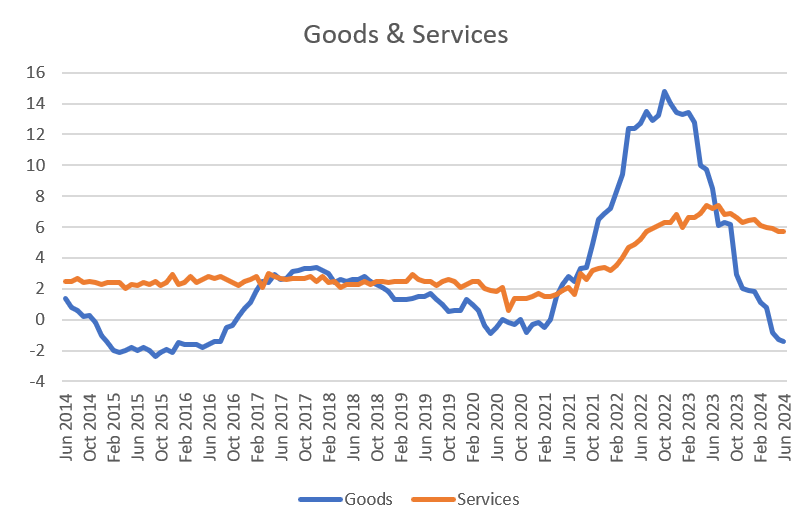

Another way to cut the data, and perhaps the simplest way to envisage what is happening with the process across the economy as a whole, is to simply divide inflation into goods prices and service prices. Each represents around half of inflation in Britain (or more precisely, services are 53.5% of the total basket and goods are 46.5%).

Taken as a whole, goods prices in Britain are now actually falling. Although they are still well above the levels seen in 2019.

In general, goods prices tend to be more reflective of global conditions and service prices more reflective of local factors. Whilst a car can be purchased from overseas, one does not usually get one’s haircut abroad.

The chart above has two causes for concern for monetary policy setters. Firstly whilst goods prices might fall for a while to offset some of the large climb of 2021-2023, that is unlikely to last for the foreseeable future. The BOE cannot rely on falling goods prices to keep inflation at 2% for the medium term. More importantly, service price inflation is both still too high and also not yet falling at a fast enough pace. If the current pace of decline – which has been in place since late 2022 – were to continue it would be around 2029 before service price inflation returned to 2%.

The biggest factor between service price changes tends to be wage growth. Other things – like energy prices – certainly play a role, but in the longer run service price changes tend to reflect pressures coming from the jobs market.

The best indicator to watch around wage pressures in recent years has been the quarterly survey by the BOE’s agent network of so-called “decision makers”.

The chart below shows the results of the most recent Decision Maker Panel on earnings.

SORBUS: Bank of England Decision Maker Panel survey – 2024 Q2

The representatives surveyed by the BOE reckon wage growth is still running at around 6% per year although down from the peak. That is broadly in line with service price changes. And whilst they expect it to fall to closer to 4% next year, that may still be a little high for the BOE.

The best takeaway from all of this is perhaps to be cheerful that inflation is back at target but not to get too carried away and assume interest rates are set to fall too sharply in the months ahead.

Good price disinflation has been responsible for much of the fall in headline inflation and that cannot be relied upon to last forever. Whilst the BOE, like other central banks, is shuffling closer to modest reductions in interest rates, as long as wage pressures and service price pressures remain elevated any such reductions in interest rates are likely to be modest.

|

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING US PCE Inflation, 26th July – Personal Consumption Expenditure inflation is the Fed’s preferred gauge of domestic price pressures. This is the key data to watch when attempting to work out quite how fast and far the Fed will cut. Caixan PMI, 1st August – The Caixan survey of Purchasing Managers is the best – and most timely – snapshot of how Chinese manufacturing is faring. And Chinese manufacturing output has an outsized footprint on both global growth and global price pressures. This is something to which Spotlight will be returning soon. |