SORBUS spotlight: After the war

It has been more than two years since Russia invaded Ukraine. The war itself has bogged down into a vicious stalemate and the direct economic impacts on Ukraine’s allies have fallen back as global energy prices have receded. However the conflict will eventually end, it seems likely to herald large changes in the structure of the global economy, reshaping global energy markets and pushing defence spending higher.

Whilst Ukraine has spent more than two years defending itself in the largest land war seen in Europe since the 1940s, its Western allies have found themselves engaged in an economic war against Russia. It is this economic war, rather than the actual fighting, which will have the more lasting impact on the global macroeconomy.

The economic war has played out in three distinct arenas – economic aid to Ukraine, sanctions on Russia and Russia’s use of its energy as a weapon – all of which are likely to still be felt into the late 2020s and beyond.

According to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy’s tracker, between January 2022 and October 2023 Western states committed more than €230bn in military, financial and humanitarian aid to Ukraine. To give some context to that figure, Ukraine’s pre-war GDP was around $200bn. The committed support in the first 20 or so months of the conflict represents around 125% of pre-war Ukrainian national income. That is, by any definition, a very large number – even in global macroeconomic terms. It is also very large in the longer history of economic aid in warfare. By contrast US Lend-Lease aid to Britain in the Second World War, widely recognised as crucial, peaked at around 20% of national income in 1944. Proportionally then, Western economic and logistical support for Ukraine’s war effort has been more than five times as large as that Britain received from across the Atlantic during the Second World War.

The future of that aid is now in doubt. Depending on how the US elections play out, the flow from the United States may wind down in 2025. Europe will be forced to either increase its own support or watch Ukraine endure defeat.

But whether the military and financial aid continues to flow or not, few doubt that the war will have had a more profound impact on the global economy.

The Russian economy, at first glance, appears to have weathered the imposition of sanctions remarkably well. Those sanctions went well beyond the expected measures and included freezing the assets of Russia’s Central Bank, something almost without parallel in recent economic history. Back in February 2022 commentators debated whether the hit to the Russian economy would be as bad as that experienced in its 1998 default or whether, as some of the more excitable analysts believed, it would be as bad as the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s or even the collapse of the Tsarist regime in 1917.

In the end the Russian economy escaped with a contraction of around 2.5% in 2022 and stabilised in 2023. The IMF expects growth of perhaps 2.6% this year and 1.1% in 2025. Whilst that is below what was expected before the war it is certainly a reasonable performance and far from the predictions of a Russian economic catastrophe.

Still, one needs to be careful with the numbers. Much of the growth represents the impact of industrial mobilisation for war and higher defence spending. Defence and security spending now amounts to almost 40% of Russia’s government budget and whilst making shells to fire in eastern Ukraine certainly adds to total economic output, it does not add to economic well-being. High inflation is eroding living standards and Russian consumers are suffering. And whilst the headline growth numbers look decent when compared to developed economies, the IMF forecasts that Russian growth figures will lag more comparable emerging European economies in 2024. More significantly, the sanctions are restricting access to advanced technologies and are likely, in the longer run, to crimp Russian productivity growth and slow GDP growth over the medium term.

The sanctions did not land a knockout blow on Russia’s economy but nor did Russia’s counter measures, cutting back on the energy supply to Europe, achieve its own aims of forcing a change in Western policy.

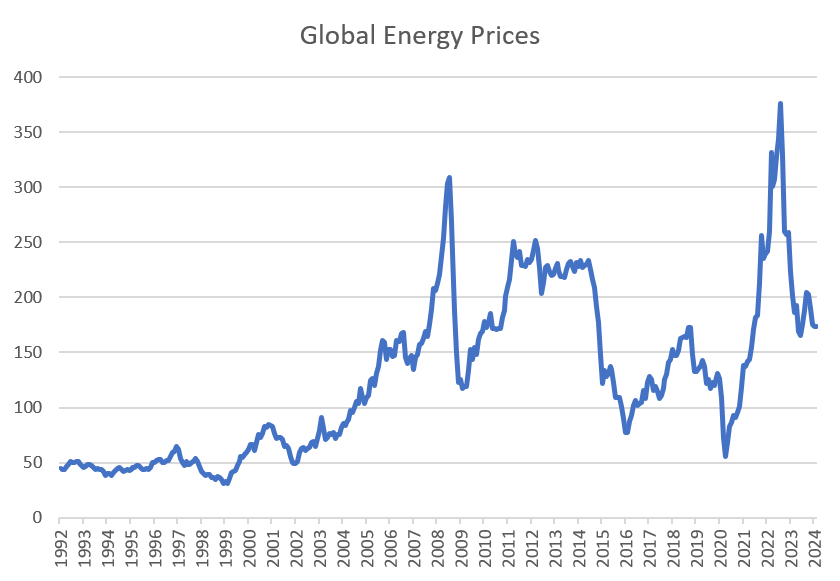

The energy price spike associated with the war was substantial.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, St Louis Fed (data as at: 18/03/2024)

What made it doubly significant was that global energy prices were already elevated at the beginning of the conflict. The global reopening in 2021 had seen energy demand return to normal levels quickly whilst energy suppliers struggled to restart production. The result was a spike in prices which began in 2021. The war pushed that spike ever higher.

The economic pain endured by households and businesses from two years of ultra-high inflation was certainly material – British households endured their steepest two year fall in real incomes since modern records began in the 1950s. And the impact on government finances, as energy bills were subsidised was equally severe. But energy prices have now fallen as energy markets have reshaped, which is the more important factor for the long run.

Europe is the case in point.

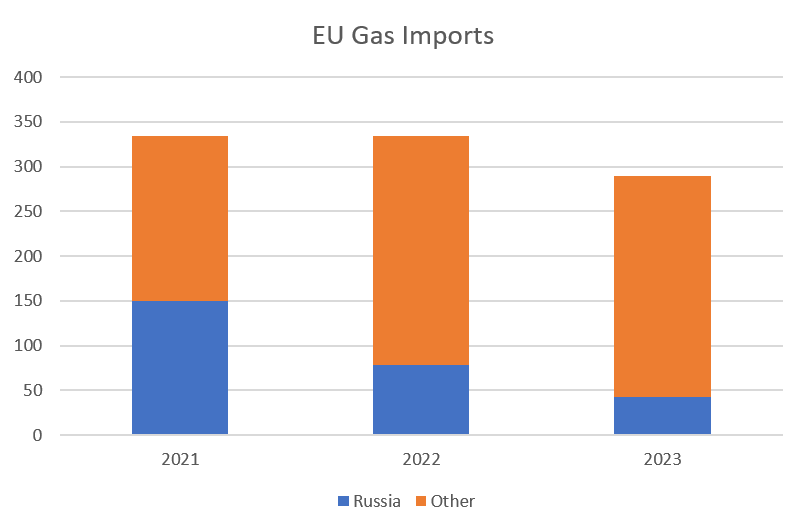

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, European Council of the EU (data as at: 18/03/2024)

On the eve of the war, more than 40% of the European Union’s natural gas came from Russia. Last year, that had fallen closer to 15%.

That change has been driven by three factors. Firstly supplies from Norway, Algeria, the United States and Qatar have been stepped up with ex Russia imports growing by 62.9 billion cubic metres (BCM) whilst Russian imports fell by 107.3 BCM between 2021 and 2023. More importantly the domestic energy mix has shifted towards more use of renewables to lessen dependence on gas overall. And finally, energy use has fallen slightly.

One of the consequences of the conflict is that Europe seems determined to kick its addiction to Russian gas. A recent analysis by the IMF forecasts that by 2030 Europe’s carbon emissions will be around 5% lower as a direct result of the war and its energy security in a much better shape. The pain of 2022 and 2023 is unlikely to be repeated and the direct lasting economic impact of the war is estimated at less than 1% of GDP.

Russia by contrast is likely to suffer more lasting damage from its own use of the energy weapon. With European markets closed, expensive capital spending will be required to create new pipelines to China to sell its natural resources. Beijing, which can see Russia will have little choice but to sell gas to it, will almost certainly be able to negotiate a lower price. The overall impact is likely to be a hit to Russia’s GDP in the region of 2-5% of national income and a small boost to Chinese GDP.

Reshaped global energy markets are not the only long-term economic consequence of the war. The other is higher defence spending globally.

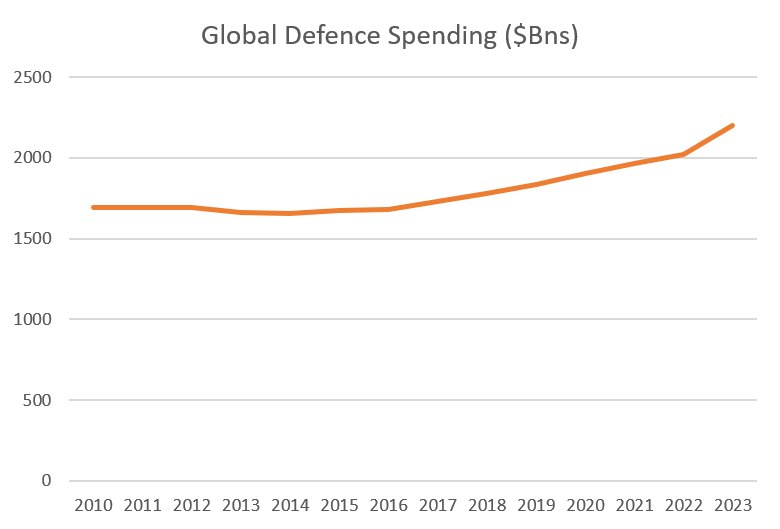

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, IISS Military Balance (data as at: 18/03/2024)

Global defence spending leapt by 9% in 2023 and is expected to grow at a similar rate in 2025.

In effect the war has demonstrated that the planning assumptions on which many Western militaries operated for decades are out of date and need rethinking. The case in point is the 155mm shell – the standard high explosive round deployed by modern long range artillery.

Ukraine is currently firing 6-7,000 such shells each day and its military believes this rate is inadequate. The US has run down its stockpiles, which were believed to be more than adequate to fight a war with the artillery intensity of the kind experienced in Iraq and Afghanistan, by transferring one million such shells to Ukraine since 2022. US monthly production, as of the beginning of the war, ran at under 3,500 per month.

It does not take a logistical genius to see the disconnect between Ukrainian daily usage and pre-war monthly production rates. The obvious lesson that Western military planners have taken from this is that war against, in military terms, a near-peer adversary will be far more artillery-intensive than the counter insurgencies Western militaries have generally fought over the past two decades. The US is now aiming to bring monthly production rates up to 40,000 a month by 2025 and European peers are aiming for similar. Even that though may not be enough.

And whilst 155mm shells have been the totemic shortage item, the list is far wider.

Higher defence spending is here to stay as Western militaries retool themselves for a different type of conflict.

The war in Ukraine has reshaped the global economy. Europe’s dependence on Russian gas has dramatically shrunk, bringing forward investment in renewable energy and lessening dependence on fossil fuels. China is set to enjoy cheaper energy as a result. Russia’s own economy has weathered the conflict better than many expected but is likely to be smaller and slower growing as a long term result. But more generally the war has forced a reappraisal in Western defence planning and promoted serious investment in the defence industrial base. That looks set to last for the rest of the decade.

|

What we are watching Eurozone Inflation, 3 April: The European Central Bank may have more room to cut rates than the US Federal Reserve this year. Whilst US inflation remains persistent at a level higher than the central bank desires, progress has been faster in Europe. It will be worth watching to see if this trend continues. US Retail sales, 15th April: The US consumer continues to spend. That has been great news for US firms focussed on supplying households but continues to worry the Fed. IMF Spring Meetings, 19-21 April: The highlight of the IMF’s Spring Meetings will be the updated World Economic Outlook forecasts, the best internationally comparable set of global macro forecasts. |