SORBUS spotlight: central banking gets exciting

In 2022 we have seen the first decisive steps in unwinding the largest economic experiment ever undertaken: the mass injection of debt and liquidity into the economy after the financial crisis. Surging inflation is now compelling central bankers and governments to react.

We believe the scale of current events suggest a different way for us to communicate our thoughts and analysis on what we believe are the subjects that matter.

This new publication is a way for us to dig deeper into economic and geo-political developments and how they influence the investment decisions we make to protect and grow our clients’ wealth.

CENTRAL BANKING GETS EXCITING

The mood amongst central bankers has shifted across the advanced economies. Rates are heading up.

John Maynard Keynes once wrote that “if economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists, that would be splendid”. Most central bankers would agree. The ideal central banker has a reputation akin to that of a successful dentist: dependable, technically proficient and, just a little, dull. Dullness is an underrated virtue, no one really wants an exciting dentist – and the same can be said of central bankers.

Sadly for us central bankers are becoming anything but dull. A year ago members of the Bank of England’s rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee were publicly debating whether or not interest rates would have to be cut below zero to safeguard the recovery. By the middle of 2021 their tune had changed to a steady drum beat of signals that interest rates would be heading up rather than down. Then in November they surprised markets by holding, only to deliver an unexpected hike in December. This week they raised interest rates again, from 0.25% to 0.5%, with four of the committee’s nine members dissenting and instead preferring an immediate increase of 0.5%.

The Bank of England is not the only central bank suddenly becoming less predictable. On the same day that the BOE raised rates, Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, suggested the ECB would soon be following them. That is an abrupt shift from a message just before Christmas that no rate rises were likely in the Eurozone before 2023. Across the Atlantic, the same hawkish shift has been observed. Jay Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve, spent most of 2021 arguing that the rise in inflation would prove ‘transitory’ before deciding, in the Autumn, to ‘retire’ the word. Instead, he is now talking up the possibility of three or four rate hikes in the coming year.

Just six months ago markets broadly expected interest rates to remain flat for most of 2022 at or near historic lows, now across Britain, the US, Canada, Australia, and the Eurozone investors are bracing for rates to rise by 1-1.5%, the most significant global tightening since before the 2008 crash.

It has been a long time since households, firms and investors outside of the US have faced a real tightening cycle. While the Federal Reserve increased US rates from zero to 2.5% between 2016 and 2019, the ECB has not increased rates since 2011. In Britain the BOE’s last tightening cycle only saw rates rise from 0.25% to 0.75% over the course of 2017 and 2018.

With central banks clearly spooked by higher inflation this cycle of hikes looks set to be both faster and steeper than anything seen over the last 15 years. Indeed, this is the first time the Bank of England has hiked at consecutive meetings since 2007. But while the pace of the hikes may reassemble the hiking cycles of the pre-2008 world, the peak will likely be lower and the direct impacts on the economy looks set to be rather different.

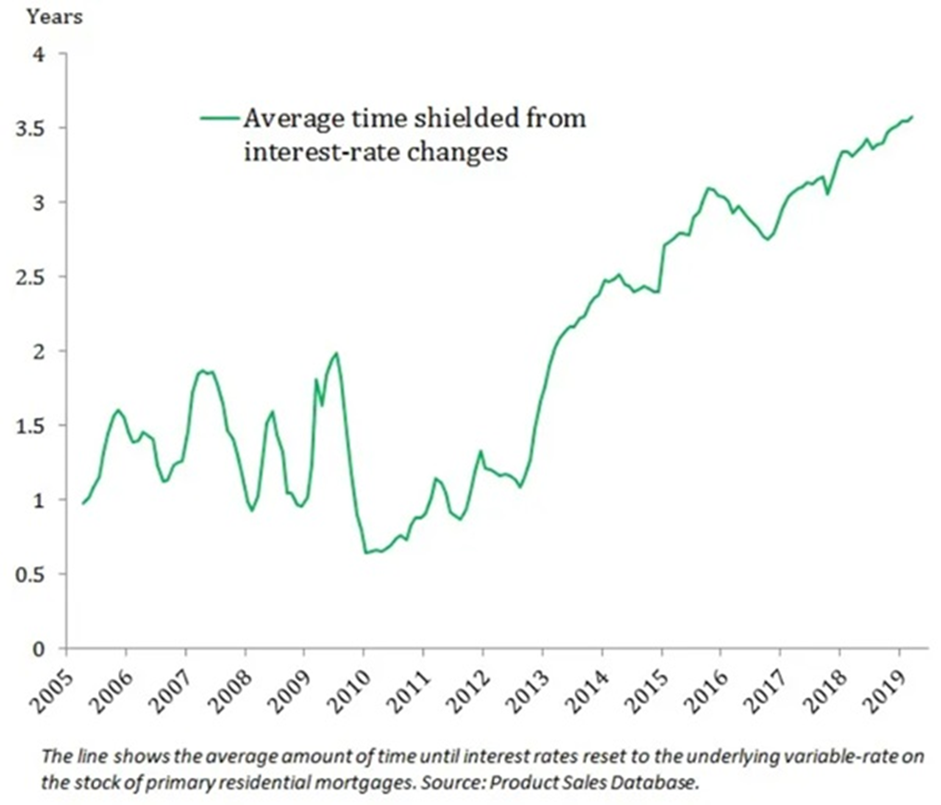

Understanding how interest rates affected the British economy used to be relatively straightforward. Back in the mid-2000s around 40% of British households had a mortgage, compared to more like 30% today. What is more, the structure of the mortgage market was strikingly different. More than 90% of the mortgages taken out in Britain in the last five years have been on a fixed rate, compared to less than 25% in the years before the financial crisis. Twenty years ago a 0.25% increase in the Bank of England’s base rate would feed directly into the monthly mortgage payments of around one quarter of British households compared to closer to one in twenty today. An analysis by the Bank’s staff suggests that it will now take an average of around 3.5 years for mortgage payers to feel the impact of rising rates.

Households, in other words, are more shielded from rate hikes than in the past.

For firms though, the picture is more mixed. Floating rate debt is more common but balance sheets, in aggregate, do not look too stretched. Indeed, some of the tech giants hold so much cash that any increase in deposit rates may even boost their free cash flow. Google, for example, is sitting on a $142bn cash pile and almost no debt. A 1% rise in US interest rates should boost free cash flow by over $1bn, a very counterintuitive result.

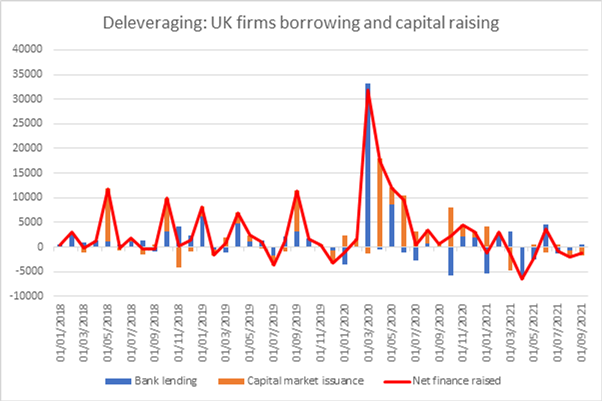

Big Tech is an unusual example but not entirely atypical. British firms borrowed heavily, at generous terms, as the pandemic struck and government backed cheap loans became available but have deleveraged their balance sheets over the course of 2021.

Even a 1% rise in rates over the coming 12 months is unlikely to push up existing debt service levels to unbearable levels for most firms. Rather than hitting households and firms by raising the cost of existing debts, this tightening cycle will instead make itself felt via a slowing in new borrowing and through financial markets.

The change in outlook has already rippled through global bond markets. One year ago almost 20% of all bonds carried a negative yield versus under 10% today. The proportion yielding under 1% has fallen from over 70% to just 34%. Capital raising is becoming more costly.

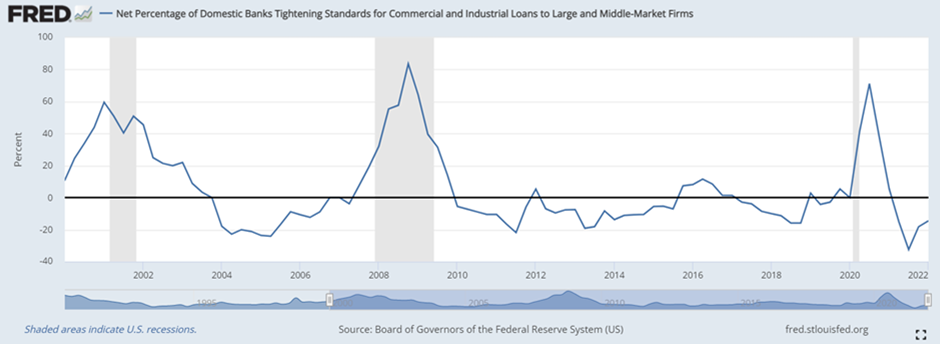

And so too is bank lending. In the US, surveys of loan officers suggest credit conditions are already tightening:

The British and European data will be available later this month and should show a similar trend.

The mood amongst central banks have swung decisively in the past few weeks. Firms and households across the advanced economies find themselves facing a monetary policy tightening cycle. The mechanisms through which that cycle will affect the economy may have changed since the 2000s – it is now less about raising the cost of existing debts and more about deterring the taking-on of new ones – but the aims of policy remain unchanged. The Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have all become concerned that their economies are running too hot, that demand growth is outstripping supply and that without steps to constrain this, inflation will remain uncomfortably high. The point of increasing rates is to cool growth, slow investment and take some pressure out of the labour market. That almost certainly means weaker asset price growth, higher unemployment and lower corporate profits. But that is a feature not a bug. For more than a decade global central banks have been in a supportive mood; more likely to fret about inflation being too low rather than high. That has changed. The hawkish turn of the last few weeks will have lasting consequences: credit conditions for firms will begin to tighten, debt service costs will slowly head upwards and financial markets will become more unsettled. Business models built on the availability of cheap borrowing will be tested and markets will become more volatile.

The question is no longer when will the hiking start but rather how high will rates go?

In the direct trade off between damaging the economy with rising interest rates and damaging the economy through surging inflation there is only one side that will prevail. The economic costs of raising interest rates will be blamed directly upon governments and central banks, the blame for high inflation is more easily deflected onto other parties. The evidence of the last six months shows that it is inflation that poses the greater risk and requires our closest attention.

COMING UP

15th February: Eurozone GDP for Q4 2021. The Eurozone has had a surprisingly successful pandemic, at least in economic terms. Employment rates – unlike in Britain or America – are actually above their pre-pandemic level and whilst inflation (at over 5%) is high, it remains below the pace of price rises seen in Britain and the US. The GDP release for Q4 2021 should show the level of economic output returning to its pre-pandemic peak, a good three or four months before Britain achieves the same.

15th February: British Labour Market Stats. The Bank of England is watching the labour market even more closely than normal. While unemployment is low, the number of people in work remains materially below where it was in March 2020. Around one million workers are “missing” adding to talk of labour shortages and helping to push wage growth higher. The key things to watch are not so much the headline level of unemployment but whether the number of vacancies is continuing to rise and what is happening to pay growth.

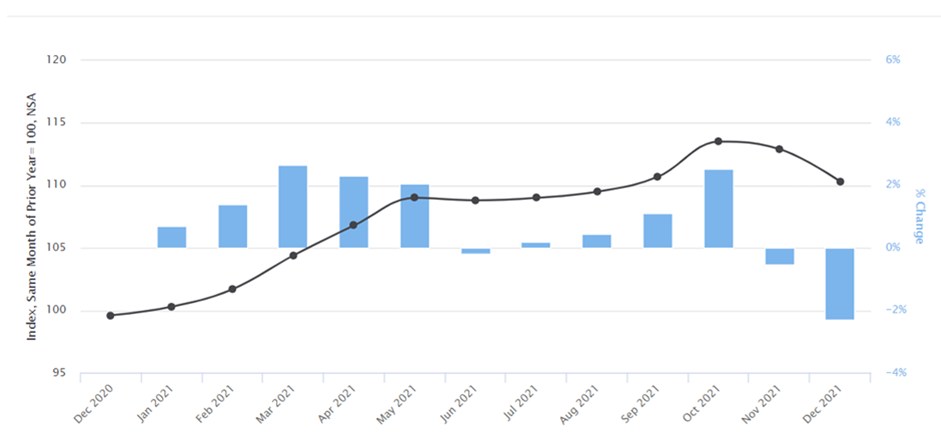

16th February: Chinese inflation data. Aside from energy bills, the single biggest driver of global inflation over the past year has been goods prices. China, as the key global goods producer, usually provides an early indication of the goods price outlook. In particular, Chinese producer price inflation is an excellent lead indicator of future price pressures.

A dip in the rate of increases towards the end of 2021 has given some hope that wider global goods price inflation may abate in the months ahead. But the combination of the omicron wave of covid together with China’s firm zero-covid approach of rapid lockdowns on any spike in cases, may well have caused cost pressures to rise once again.