Exposing investing costs

“No good reasons have been put forward for why all the costs of investment management, both visible and hidden, should not ultimately be fully disclosed”

David Blake, Pensions Institute, Cass Business School

In 2012 the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) was intended to provide investors with transparency over the fees they pay.

In October analysis of the “all-in” costs for clients discovered that charges from some high street investment managers were up to 7.5% in the first year. In November it was revealed that BlackRock, the largest asset manager in the world, required its pension customers to sign a non-disclosure agreement before it would reveal what it charges them – preventing them from comparing costs and securing the best deals for their clients.

So far a modicum of progress has been made but much remains to be done. The reality is that as far as the client is concerned they have a little more transparency over the fees they pay but the costs are little different. An opportunity for the financial services industry to fundamentally reassess the methodology for how it is paid has been squandered.

It is worth having a look at where we have ended up and explore why the industry is so resistant to innovation.

Firstly let us unpack the fees. What retail clients pay for access to financial services has always been famously obscure but there are three basic fees:

- for custody of the clients assets (usually via a platform),

- for advice (usually paid to a financial adviser of some sort),

- fund management fees (most retail clients are advised to invest via collective investment products such as Unit Trusts, OEICS, ETFs and Investment Trusts).

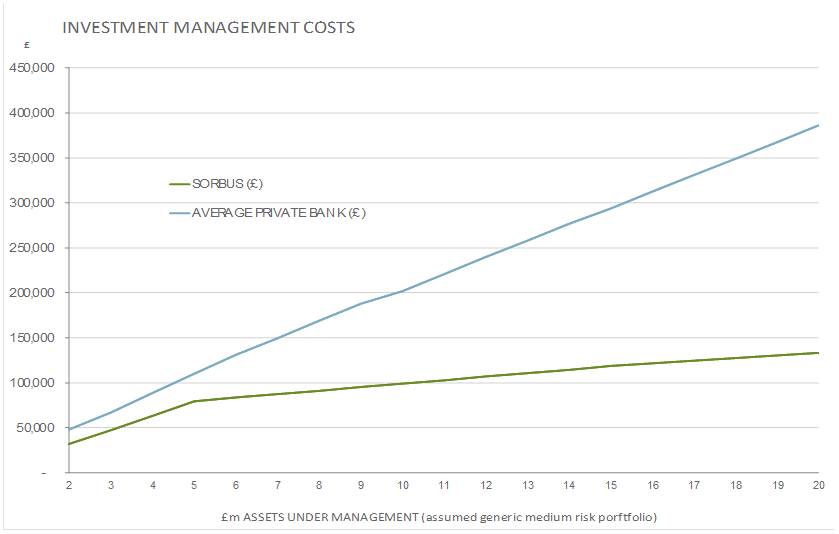

How these three were packaged and paid for depends on whom the client uses – some were segregated while in many cases they were all bundled together. If you use a private bank for example, there may be an explicit custody fee but usually if you pay for advice then the custody fees are subsumed into the advice fees charged by the bank. These fees are usually represented as a percentage of assets under management – an ad valorem fee – and on average start at around 1.% scaling down to around 0.65% once assets under management exceed £50m – these figures exclude VAT which is payable. As you can see there is virtually no price competition between the main private banks.

In addition to these charges there are the fund charges – the costs of the investments they buy for you. The most charitable estimate of these is that they equate to 1.08% or 108bps on average. The costs will be substantially higher if you are sold anything that has the same brand as your adviser or if they include words such as “structured product” on the label.

They are so high because the private banks persist in investing their client’s money in expensive actively managed funds that have been proven repeatedly to underperform (because of the high costs). For comparison our average portfolio fund charges are 0.28% or 28bps because we mostly invest directly in companies and cut out the middleman (the fund manager) and where we do use funds we will often use cheap passive exchange traded funds (ETF’s) where we do not consider that paying for active management will add any value.

In 2014 less than 10% of active managers beat their benchmark. While the private banks stubbornly stick to the high cost option for their clients the industry is moving away from them: there were withdrawals of £92bn from expensive actively managed funds in 2014 and additions of £156bn to cheap passive ETF’s.

As such, and with a highly charitable set of assumptions, if we add the 1.08% cost of the funds to the investment management costs and add the VAT the investment management/private bank total costs start at 2.4% per annum (though they can be substantially higher).

There is one striking similarity across all of these fees though, they are all ad valorem – based on the value of assets under management. Ad valorem fees imply that the cost of providing the financial services rises in proportion to the value of assets under management. This is one of the great unspoken myths in financial services. If you have an investment in a fund of say £5m, and you add another £5m to it, the cost to the investment manager is, to all intents and purposes nil, but your annual costs have just doubled.

The financial services industry has in effect been placing a tax on their wealthiest clients. It is obvious to understand the motivation of the private banks for imposing such a charging structure. Over time the value of assets under management should increase at least in line with inflation protecting the bank’s revenue and profits.

They have to charge this amount for a simple reason – they have many mouths to feed. When you see your private banker you are not just paying for his fees you are paying for his bosses and their bonuses, for the people who actually manage the money, the bank’s shareholders, the bank’s creditors and the banks marble-lined Mayfair offices.

NEW FEE STRUCTURES

Our view is that these are essentially discretionary costs and they can be avoided with ease. We established SORBUS as a partnership in order to avoid external shareholders (we are 100% staff owned), we have no debt, we have no management team (nor their bonuses) and we feel that our clients receive little value from basing ourselves in Mayfair.

Our staff and partners typically have greater experience and technical qualifications than their private bank peers and we have access to the same data and research but all the other costs have been removed.

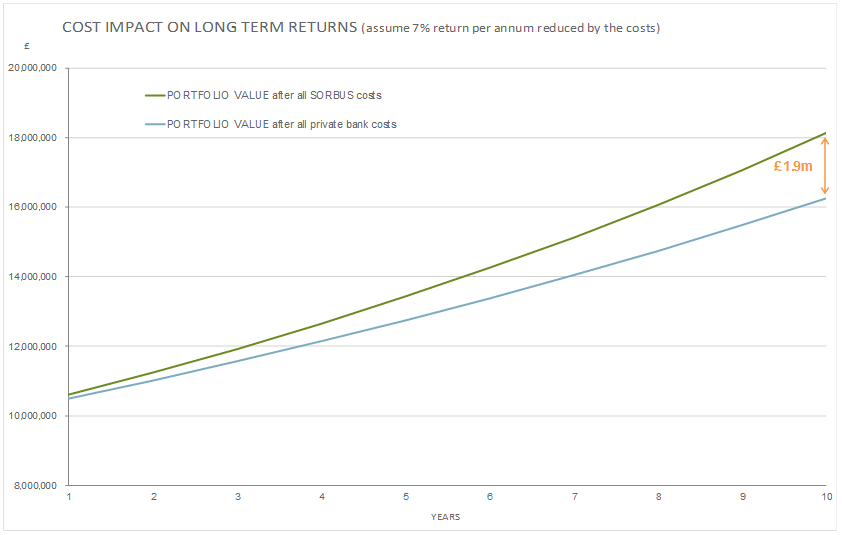

The following graphic represents our estimate of the value that eliminating unnecessary costs provides for our clients. Assuming the same 7% return a client with £10m to invest is £1.9m better off after 10 years.

Another way of looking at it is that if you use a private bank and your portfolio achieves a growth of 7% a year for the next ten years, 46% of these returns will be paid to the bank in various fees and charges.