Bank attraction

“Bank valuation anomalies will be made clear over the coming months and years as resolution progresses.”

Andy Lees, MacroStrategy

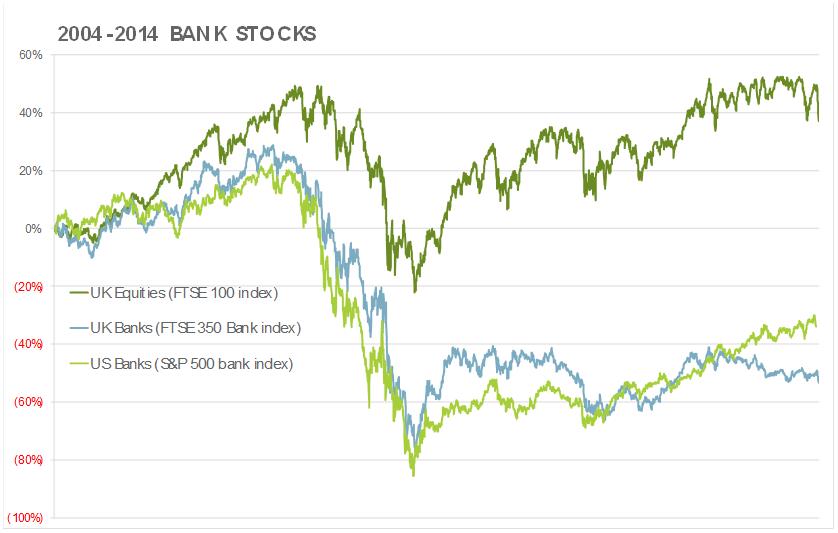

We have previously noted that UK banks were starting to look interesting from an investment perspective and we now examine this in more detail. What inspired this reassessment is twofold: there is evidence that bank lending is increasing and that bank valuations have lagged a stock market recovery

The cause of the typical banking crisis is reckless and excessive lending to usually a concentrated investment area – in the last crisis property. The resolution to a bank crisis is a painful and lengthy balance sheet repair exercise. A feature of this recovery is that the banks understated the losses from their non-performing loans (NPL’s). This happens for a few reasons but two major influences are that the executives are initially in denial that the areas they lent to could get into such trouble when it had all seemed so promising, and that understating the extent of the losses delays and reduces the criticism due to them for their involvement in the crisis.

In the last crisis this understatement took the form of what became known as “extend and pretend” and eventually “delay and pray”. When a loan to a commercial property company was in danger of becoming a NPL because rents were falling, vacancies were rising and covenants were in danger of being breached the banks took steps to avoid recognising the economic reality. In their context it was preferable to relax the covenants and allow the borrower more time to try and turn the asset around. The banks were intensely capital constrained and would rather reduce their interest income than foreclose and recognise a significant capital loss. Another way of looking at it is that they had a finite amount of profitability they could write off each year recognising losses. Over the last five years they have finally mustered (and written off) sufficient profits that the NPL pile has shrunk to manageable proportions.

Previous crises provide a reference point for the extent and rate of recognising write-offs but when banks are not being wholly honest then the extent of these hidden losses is largely unknowable. A major signal is when, after five straight years of decline, banks start to lend again. If the bank management is finally comfortable to gradually increase lending it implies that their hidden losses have been managed down or covered sufficiently for normal lending conditions to resume. Loan growth has been described as “the one activity that differentiates the resolved bank from the still technically insolvent one”.

The valuation case is also interesting. UK banks, relative to the FTSE100, have lost two thirds of their value since the crisis broke. They certainly deserved a beating and it should also be acknowledged that the profitability of banking faces structural challenges post-crisis; things have changed. The costs of compliance and regulation have risen dramatically, as has the willingness of regulators to impose fines, demand increases in capital and restrict potentially lucrative activities. However it does not require a normalisation back to pre-crisis profit levels for banks to look attractive. After the size of the fall even with diminished future profitability prospects they look keenly priced.

SOURCE: SORBUS, Bloomberg

However there are three variables we should consider before concluding the valuation case:

- Are banks still vulnerable to a further financial crisis?

- Do they have latent liabilities?

- Are they vulnerable to residential mortgage defaults if/when interest rates rise?

Are banks still vulnerable to a further financial crisis?

For the first question the answer is largely “no”.

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) has recently subjected UK banks to “the most stringent stress test in history”. The Co-op bank failed laughably but the other seven got through mostly unscathed. To be fair the stress tests were rigorous this time unlike those in 2008 which appear to have been designed to ensure the major banks, Barclays in particular, appeared solvent when they were, at the time, insolvent.

The stresses applied were:

- GDP falls by 3.5% by 2015

- Unemployment rises to 12%

- Residential property prices collapse by 30%

- Interest rates go up to 4%

- 10 year gilt yields soar to 6%

After these shocks banks must maintain Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) of at least 4.5%, calculated on a fully loaded Basel 3 basis, the harshest measure.

While one can construct scenarios that might lead to (say) GDP falling by 3.5%, it is inconceivable that this would take place at the same time as base rates rise to 4% and gilt yields rise to 6%. We believe that these tests are sufficiently rigorous and reinforce our contention that the journey of recovery in the UK banking system is mostly complete. UK banks can withstand another financial crisis without further recourse to the state to shore up their balance sheets.

Do banks have further latent liabilities?

On balance we would say that it is unlikely. As an example the major volatility of the last month is to be found in oil and the rouble. Oil exploration is notoriously capital intensive and with oil prices sub $60 it is not hard to envisage scenarios where tranches of the debt default. Energy bonds have dominated the riskier end of the debt markets (45% of 2014 bonds) and now represent 16% of total issuance. However the main exposure is US based. Wells Fargo has $37bn, JP Morgan $31.7bn but the numbers after these two tail off fast. HSBC and RBS have exposures of around $12bn; not so little it can be ignored but not a systemic risk even under adverse scenarios. Similarly there is some European exposure to Russian banks and financial systems but little in the UK, and what little there is has largely been crystallised by the sanctions.

It is possible that there are further miss-selling scandals similar to the Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) debacle. One would hope not but recent experience has taught us to expect behaviours to disappoint on the downside.

INTEREST RATE RISK

Will this cause significant residential mortgage defaults? Our analysis suggests that this is a likely outcome though the scale depends on the nature of the tightening and economic conditions prevailing at the time and in the intervening period. In effect you will be able to see it coming even if the timing and extent of the issue is beyond analysis at the moment. We can worry about this later.

We have had very little exposure to the UK banking sector over the financial crisis. We will be reversing this position should these positive trends persist.