Mean reversion

“Contrariwise,” continued Tweedledee, “if it was so, it might be; and if it were so, it would be; but as it isn’t, it ain’t. That’s logic.”

Lewis Carroll

Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871)

Property prices boomed in the years up to the start of the financial crisis, however after steep declines in 2007 and 2008 there has been a surprisingly sharp recovery. Over the five year period (from the beginning of 2007) property investors received a zero total (capital and income) return: on average the income received from rents has been cancelled out by declining capital values. [source IPD]

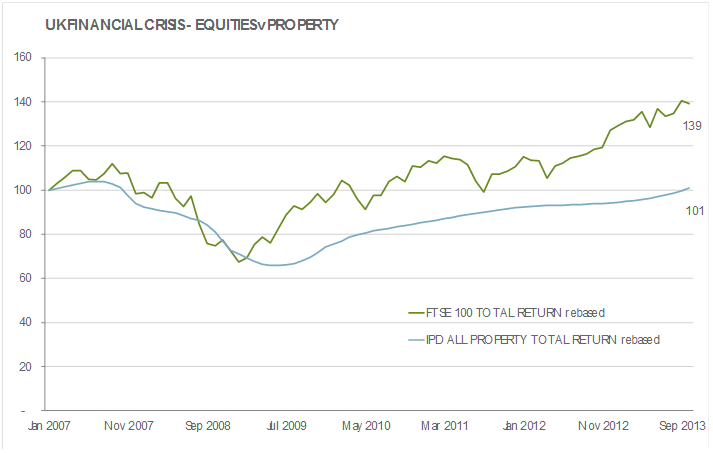

The value of companies (the stock market) has behaved similarly: a sharp fall from the middle of 2007 to a trough in early 2009 followed by a strong rebound. Equities have delivered higher returns than property during this period but this is more of a function of starting the crisis less overvalued than property. (figure 1)

The US economy has grown by 1.6% so far in 2013 but its stock market is up by 23%. Similarly, in the UK the economy has grown by 1.4% but the stock market is up by 11%. These two simple points of data reveal an interesting trend that has occurred to most assets over the last five years – their value has been growing at a faster rate than the economies in which they are based.

The strong recovery of both assets sits at odds with one of the most important concepts in investing – mean reversion.

FIGURE 1 SOURCE: SORBUS PARTNERS, Bloomberg, IPD

Mean reversion

While everyone who has ever made an investment will no doubt be familiar with the phrase “past returns are not indicative of future returns”, this axiom is in fact only true when looking at short time scales. This does not diminish its value as a warning as most investors whether amateur or professional are inordinately influenced by recent historical evidence. If an investment has done well over the last couple of years investors are prone to extrapolate this recent history and envisage valuations stretching ever upwards at this steep rate. However over longer time periods past returns are a good predictor of long term future returns.

This is not particularly revolutionary as a concept if we take a quick look at first principles. If the cost of lending to the government (the “risk-free” rate) is x%, then an investor in risky assets such as a company would demand x% + y%, y being a premium for taking the risk that he might not get his money back. How much of a risk he or she is taking is of course subjective and moves up and down with economic fortunes and sentiment. Over the last twenty five years the “risk-free” rate was 3.3% after inflation. If we say that the premium required to compensate us for the risk taken in buying equities is around 4.0% then we should expect the long term total return from equities to be x (3.3%) + y (4.0%) = 7.3%. This is in fact very close to the long term returns from equities.

Property shares some qualities with equities in that its capital value can go up and down, but it also has an element of its return (income from rents) which is more like a lower risk fixed interest investment. As such we would expect long term property returns to be somewhere between the “risk-free” rate and the returns generated from equities, which it does. The long term average returns from an asset are a valuable guide to future returns.

Mean reversion is the concept that over the short term returns from different investments can diverge significantly from their long term average, however over time the performance will gradually revert back to this long term average. If an asset has historically grown at 5% a year but over the last five years has grown at 10% a year, one might reasonably expect the next few years growth to be lower than average and return to the long term trend.

In the years running up to 2007 property investors enjoyed huge profits and a growth rate well in excess of the historic average. Since then they have had a below average return (0.1% pa) which is gradually bringing property prices back into line.

However the crucial element is that it remains considerably above this long term average trend line. The valuation of UK property is now at the same level as before the financial crisis. Can we really accept that there has been no harm done to the valuation of property by the financial crisis? An ever clearer warning signal can be seen in the returns from equities which have been 40% over the last five years (including dividends).

We know that UK economic output remains below the pre-crisis levels and that the recovery has been patchy, fragile and thin. We know that the principal funders of the property boom – the banks – are aggressively trying to shed themselves of surplus assets and shrink their loan books. So why have the valuations of property and equities remained so stubbornly above the long-term trend?

Enter the not-so-secret agent

The reality is that there is a major new external agent at play here: quantitative easing. Quantitative easing or QE is a famously complex concept to understand but in simple terms its impact is to flood financial institutions with money to ensure that they continue to function. These financial institutions would typically park this cash by lending it to the government or leaving it on deposit, but as the returns from cash deposits and gilts (loans to the government) are so thin they have felt compelled to invest in riskier assets.

It is QE that is responsible for driving up the price of equities and property, dislocating them from their natural levels. This leaves investors with difficult and unpalatable choices. Low risk assets offer no return, but risky assets are generally expensive. There are always opportunities for the skilled investor but we should not pretend that they are plentiful at the moment.

If valuations are being prevented from returning to their long-term average by an external agent then the removal of that external agent should allow prices to revert to their normal levels. At some point QE will cease and interest rates will start to rise. This will lead to a more attractive investment environment as it is guaranteed to improve the returns from low risk assets (cash and gilts) and will almost certainly improve the outlook for risk assets as their valuations should decline sharply.

So while we may be pleased that the destination will be an environment where more rational decisions can be made, the journey will make investors seasick as yields rise on gilts (meaning the price falls) and holders of other risk assets experience a possibly sharp drop in value.

It is not unreasonable to say that with choices like this it would be rational to accept the zero returns from cash and wait this out. However the “risk-free” choice is not risk-free. The financial crisis is far from over and the weaknesses of many financial institutions and governments remain unaddressed and unresolved. Counter-party risk with leaving cash on deposit cannot be dismissed, nor can the devaluing impact on money of governments running the printing presses white hot.

Additionally the investor on the sideline may be waiting a long time. Our analysis is that we are unlikely to see interest rates start to rise before 2015 and possibly much later.

Investors should accept that staying on the sideline is both risky and guaranteed to lose you a small amount. They should also accept that risk assets are expensive and likely not only to fall when QE stops but also to provide low returns over the next ten years.

Our conclusion is that buy-and-hold, a defensible strategy for many decades, is broken under the current economic conditions. The long term preservation and growth of wealth will require bold moves in and out of asset classes over the coming years. It is also likely that the liquidity of an asset will again acquire a premium as investors are unwilling to lock their cash up when there are enduring momentous but unpredictable economic conditions.