SORBUS Spotlight: Where next for the Fed?

Once a year the Federal Reserve hosts a get together for global central bankers at the Jackson Hole ranch in rural Wyoming. Global rate setters enjoy hiking, horse riding and some apparently excellent barbeques as well as hearing the latest research on global macroeconomics. It is clearly a very civilised way to keep up to date on the latest thinking.

The Fed Chair’s annual address is one of their key opportunities to communicate with financial markets. The Jackson Hole speech often sets the tone for the coming months and provides a helpful steer on both what the Fed is thinking and how it sees policy unfolding.

This year though, Chairman Powell managed to ignore the elephant in the room. His speech was, as ever, interesting.

As Powell put it, the current outlook – from a monetary policy point of view – is especially ‘challenging’.

“In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside – a challenging situation.”

‘Challenging’ is best understood as an example of typical central banker understatement; it is tricky to imagine a tougher scenario for monetary policy than rising inflationary pressure coupled with a weakening economy.

Turning to the wider economy first, Powell neatly set out the situation:

“Overall, while the labour market appears to be in balance, it is a curious kind of balance that results from a marked slowing in both the supply of and demand for workers. This unusual situation suggests that downside risks to employment are rising. And if those risks materialize, they can do so quickly in the form of sharply higher layoffs and rising unemployment.

At the same time, GDP growth has slowed notably in the first half of this year to a pace of 1.2 percent, roughly half the 2.5 percent pace in 2024. The decline in growth has largely reflected a slowdown in consumer spending.”

The pace of economic expansion has slowed sharply, and the risk of a major slowdown in the jobs market is clear.

But on the other hand:

“The effects of tariffs on consumer prices are now clearly visible. We expect those effects to accumulate over coming months, with high uncertainty about timing and amounts. The question that matters for monetary policy is whether these price increases are likely to materially raise the risk of an ongoing inflation problem. A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short lived – a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, “one-time” does not mean “all at once.” It will continue to take time for tariff increases to work their way through supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates continue to evolve, potentially prolonging the adjustment process.

It is also possible, however, that the upward pressure on prices from tariffs could spur a more lasting inflation dynamic, and that is a risk to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, who see their real incomes decline because of higher prices, demand and get higher wages from employers, setting off adverse wage–price dynamics. Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, that outcome does not seem likely.”

In other words, tariffs are definitely adding pressure to prices, and that is likely to continue for a while but – in the view of the Fed’s leadership – this slowly playing out change in the price level is unlikely to spark second round impacts due to the weakness of the wider jobs market.

That is the key judgement call outlined by Powell, – yes tariffs will push prices up, but a weak labour market means that workers will not be able to use faster price growth to bargain their own wages higher. In such circumstances, then the Fed feels able to prioritize the weaker jobs market and slowing economic momentum and reduce rates further towards neutral levels.

Taken together, this can all be read as a sign that a long running debate within the Fed has finally come to a close. Ever since this Spring, the key question has been whether or not the central bank feels able to ‘look through’ a temporary bout of above target inflation and cut rates, or whether the potential for second round effects would stay their hand. That has now been resolved: the Fed is content to respond to a weakening jobs market by cutting rates, even if inflation is higher than they desire.

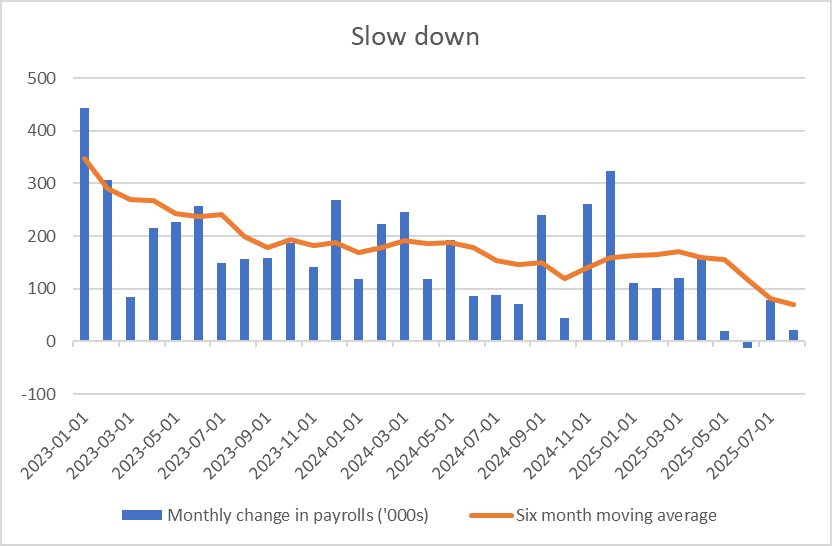

And the US jobs market has certainly slowed.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, US Bureau of Labor Statistics (data as at 05/09/2025)

Using the less volatile six monthly average of the net monthly job change figures, the rate of job creation has roughly halved over the past 12 months. The sectoral breakdown is also useful. Manufacturing jobs have been falling for four months, while those in the wholesale trade have fallen for three consecutive months. Both sectors are highly exposed to the disruptive impact of tariffs on trade.

This was the background to the Fed’s decision to resume cutting rates. On September 17th the Fed delivered its first quarter point cut of the year and signalled that two more would likely follow this year.

Normally the outlook for rates is the key talking point when it comes to discussion of the Fed. But this year has been different. A bigger question, the elephant in the room that Chairman Powell avoided at Jackson Hole, has been a rising question mark over the Fed’s independence.

President Trump has been absolutely clear that he believes policy rates should be lower. In some regards, this is nothing new. Throughout his first term in office, the President continually took to social media to argue for rate cuts.

This time around, though, the attacks have moved beyond rhetoric and political pressure. An attempt has been launched to remove Governor Lisa Cook and is currently working its way through the courts, and there is talk of reform of how regional Fed Presidents are appointed. More broadly, Chairman Powell’s term is due to end next year and replacement will be nominated by President Trump.

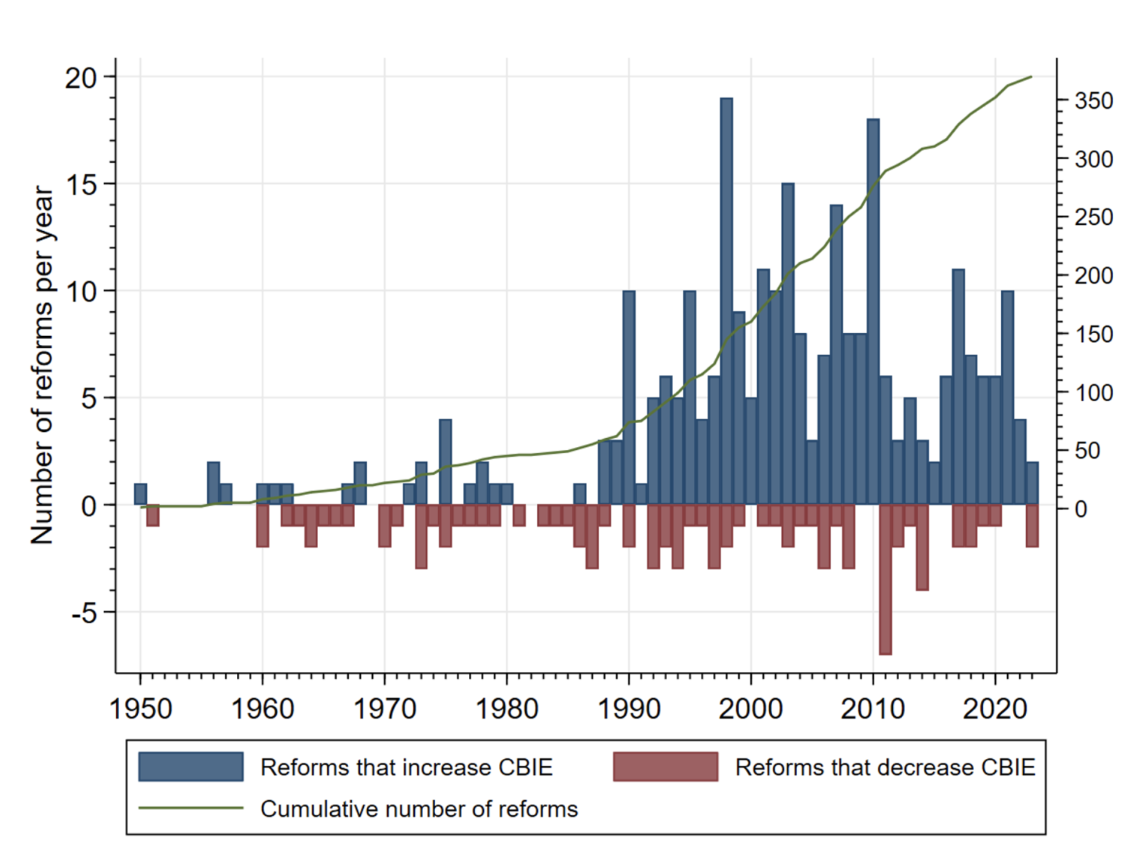

The broad history of central banks, across the globe, over the past few decades has been of rising levels of independence. Indeed, one recent study looked at measures of independence over 155 countries between 1923 and 2023:

“I identify a total of 370 reforms to central bank design, which highlight a remarkable global shift towards enhancing the independence of monetary authorities. This shift is particularly notable in the context of recent global challenges that emerged following the 2008 global financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent resurgence of inflation experienced by many high-income countries since mid-2021, which have revived the debate on the role and scope of central banks. The findings in my paper contribute to these ongoing discussions, offering a nuanced understanding of how central bank independence has been shaped and reshaped over a century. The increase in the degree of central bank independence, observed across countries with varying levels of economic development, signals a broader recognition of the importance of independent monetary policy in maintaining economic stability.”

source: Davide Romelli, CEPR (data as at 26/02/2024)

Increasing Presidential power of the Fed risks raising questions over its credibility when it comes to keeping inflation in check.

Credibility is, to an extent, a question of perception and expectations, and, in both cases, the direction of travel matters.

Take for example, the Bank of England. On many measures, it is fundamentally much less independent of the British government than the Federal Reserve is of the wider US executive branch. The government has far more control over the appointment of members of the Monetary Policy Committee and has the power to change the Bank’s inflation target whenever it desires (even if this power would only ever be used cautiously). According to Romelli’s (the author of the recent study) rankings, the BoE scores just 0.44 on his central bank independence ranking (out of a potential 1.0) compared to the Federal Reserve’s 0.61. And both banks are well below the transnational European Central Bank’s score of 0.9.

The Bank of England is generally regarded as a credible and independent central bank, and yet it is less ‘independent’ than the Fed. This does not mean that the steps that reduced the Fed’s independence to the level of the Bank would be consequence-free. When it comes to central bank independence, the direction of travel may matter just as much as the final destination.

One early sign of the possible final destination came at the most recent meeting. Stephen Miran, the newest appointment to the Fed’s board and the first Trump has made this time around, cast his first vote. Whilst the majority of the board preferred a cut of 0.25% in rates, he preferred a 0.5% cut.

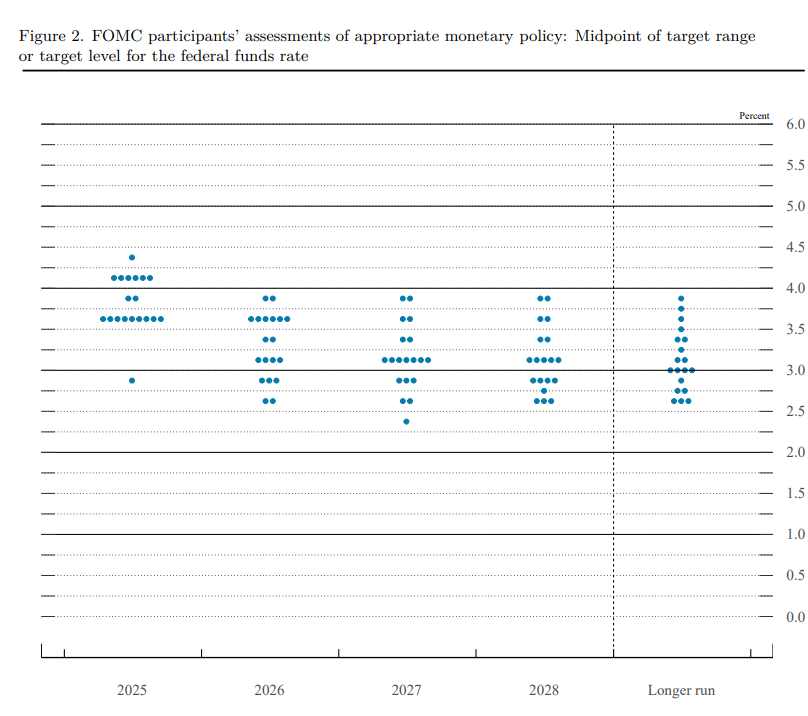

Four times a year the Fed publishes its so-called ‘dot plot’, an exercise whereby each governor – anonymously – notes where they expect interest rates to end the year.

Usually looking at the median estimate gives a useful clue as to how the board sees rates developing over the coming period.

This time around though, one dot stood out.

source: US Federal Reserve (data as at 17/09/2025)

Whilst that lone dot under 3% for the end of 2025 may not be Miran’s, it is hard to see whose else it could be.

If President Trump gets his way, and can appoint more Miran-like economists to the board, then lower rates clearly lie ahead.

|

What we are watching. US PCE Inflation, 26th September – Personal Consumption Expenditure Inflation is the Fed’s preferred gauge of price pressures. It should continue to rise, although the board has made clear they are prepared to look through this. That said, an especially hot reading could start to see the market question whether two further rate cuts this year are really certain. UK Business Investment, 30th September – British growth has been a little faster than expected for several months now. That though has been driven by higher consumption rather than investment. Faster business investment, which currently feels unlikely, will be the key to sustainable growth going into 2026. IMF, 13th October – The October IMF meetings see the release of the twice annual IMF global growth forecasts, the best cross-country comparison of what is happening in the global economy. |