SORBUS Spotlight: Sound as a dollar

It is sometimes grimly amusing to look back at the blizzard of year end outlooks released by investment banks, stockbrokers and sell side research houses. December 2024 may only be half a year ago but an awful lot has changed.

When it comes to the US dollar there was a near consensus amongst observers that President Trump’s second term would see a rising greenback. Instead, the opposite has happened.

The rationale for the stronger dollar forecast was, on the face of it, sound. The so-called Trump trade (when Trump’s poll numbers began to improve and a second term looked increasingly likely), which gripped Wall Street from the middle of last year until his inauguration in January, was relatively simple. The assumption was that President Trump would oversee a programme of tax cuts and deregulation while being relatively cautious, despite his rhetoric, on the tariff front.

Tax cuts and deregulation would both boost the animal spirits of American bosses and entrepreneurs and directly increase company earnings. For markets that meant a stronger American equity performance. When it came to bonds, the assumption was that Trump’s policy mix would see a rise in yields but not to the kind of levels which would materially slow economic growth or rattle the equity market. Of course, tax cuts would lead to a wider deficit and faster growth in general would add to inflationary pressure, so rates would be a touch higher – but that would be outweighed by the impact of the tax cuts and deregulation on both the bottom line and sentiment. Rising yields, relative to other advanced companies, would make the dollar more attractive and a stronger equity market would attract capital flows from other nations. Taken together that added up, it was assumed, to a rising dollar.

That is not how things have played out.

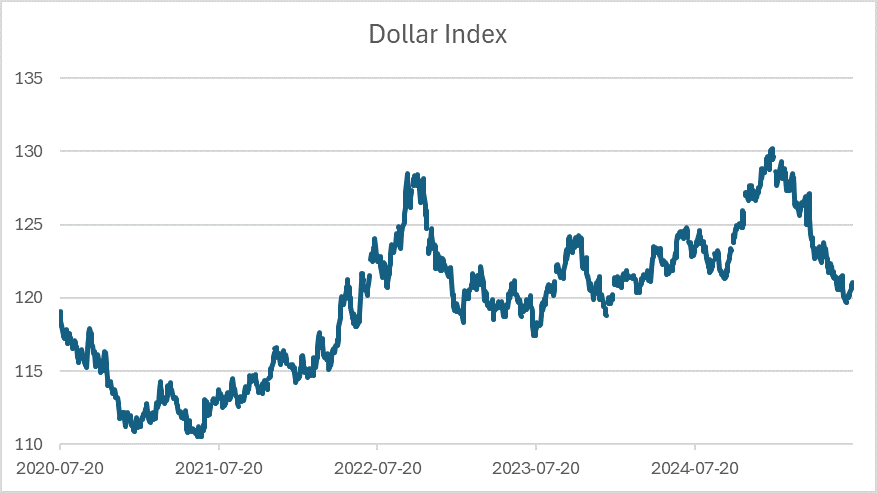

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (data as at: 22/07/2025)

Since December the 31st the broad dollar index, which tracks the value of the dollar against a broad basket of other currencies, is down by 6.7%.

That is a macroeconomically material size of movement.

If one chooses instead to use the ICE dollar index, which tracks the dollar against a smaller group of advanced economy currencies – the Euro, the Pound, the Yen, the Canadian Dollar, the Swedish Krona and the Swiss Franc – things look even worse for the greenback. On this basis the dollar fell by 10.7% between the end of December ‘24 and the end of June ‘25, marking the worst six month period for the currency since 1973 (source: SORBUS, Bloomberg).

Such a large fall in the value of the dollar has consequences. The first, and most obvious, is on inflation. A falling dollar makes US imports pricier, meaning that either inflation has to rise or the profit margins of importers will be squeezed.

The interaction of a rising dollar and tariffs makes this even trickier. The broad assumption of markets was that 2025 would see increases in US tariffs but to relatively mild levels, coupled with a stronger dollar – and that a rising dollar would offset much of the impact of higher tariffs.

Take, as a straight-forward example, US imports from the European Union. If President Trump had imposed a tariff of, say, 5% on all imports from the EU and the dollar had risen by 5% against the Euro, the net impact on US consumers would have been very small – the two movements would roughly offset each other.

Instead tariffs have been imposed at much higher levels. A broad 10% universal tariff on almost all imports, 25% on goods such as automobiles and steel and country specific rates which are often in the region of 35-50% on some trading partners. And a falling dollar magnifies rather than minimises the impact.

But the falling dollar has a direct impact on market returns too. Between the administration backing down and delaying its liberation tariffs for 90 days and the end of June, the S&P 500 rallied strongly – rising by 24% and hitting a new high. Or at least it did in dollar terms. For a Euro based investor, the currency move pulled in the direction leaving the S&P 500 up only 15% from the April lows and, crucially, still 10% off the all time high in Euro terms (source: SORBUS, Bloomberg).

This works the other way around too. In the first half of 2025, European equities rose by 15% in local currency terms but by 23% in dollar terms (source: New York Times).

In other words, a materially lower dollar – especially if such moves continue – tends to make investing in the US less return rich for overseas investors and, simultaneously, raise the effective returns available for US investors moving money abroad.

Outside of the United States, and often less appreciated in US-centric commentary, a weaker dollar tends to be a useful thing.

Movements in the dollar’s value impact the global economy through two main channels: trade and finance. More than 40% of global trade—most of it not involving America—is invoiced in dollars (source: European Central Bank). Much trade between, say, Mexico and Japan – to take one example – is invoiced in dollars rather than yen or pesos. A rising dollar raises the costs for importers, which dampens demand for goods from abroad and reduces overall trade volumes. Across much of Asia and Latin America, therefore, movements in the dollar’s value matter more than how local currencies behave. One academic study (source: European Central Bank), published in 2020, found that a 1% rise in the value of the dollar against all currencies predicts a 0.6% decline in trade between countries in the rest of the world, after controlling for other factors. But, just as importantly, this impact runs both ways. The almost 7% fall in the value of the dollar since last December should have boosted global trade by perhaps 4% relative to a scenario in which the dollar was flat.

And then there is finance. Across the developing and emerging economies borrowing in dollars is common amongst both firms and governments. It is easier to raise a syndicated global loan in US currency than in Sri Lankan Rupee. And a weaker dollar lowers the burden of such borrowing and makes meeting interest payments easier.

A weaker dollar then can be a good thing for the rest of the world, as long as the move downwards does not become too disorderly.

What is driving the out of consensus fall in the dollar? Three major factors can be identified behind the Trump trade going wrong.

The first is the somewhat chaotic policymaking of the Trump team’s first few months in office and the sequencing of the policy moves.

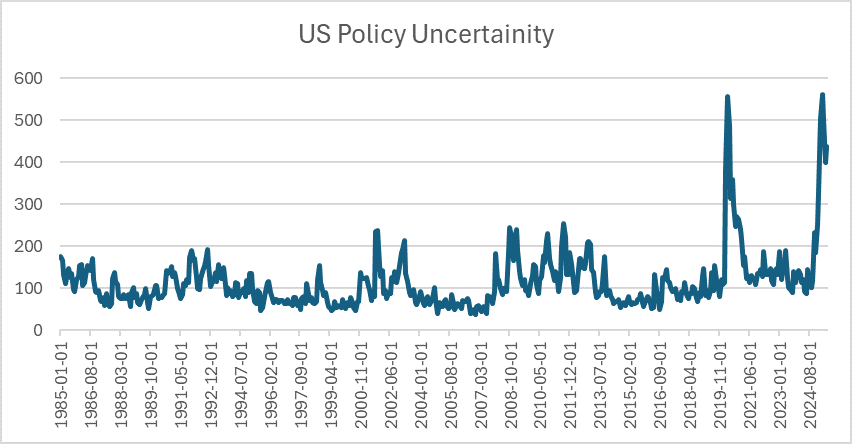

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (data as at: 22/07/2025)

The neatest way to demonstrate this is the Economic Policy Uncertainty index developed by economists at Stanford University. This simply measures mentions of economic policy uncertainty in major news sources as a share of all stories about economic policy over time.

The first months of the new administration have seen a jump in uncertainty larger even than that witnessed in the early days of the pandemic. Tariffs have been threatened, put in place, changed, and delayed sometimes multiple times in the space of a week.

In the face of extreme uncertainty, cutting exposure is the easiest response.

The sequencing too matters. Not only have tariffs been much higher than many expected, but they also came before tax cuts and deregulation. Had the Trump administration followed the play book expected by markets and spent their first months in office carrying out business friendly policies before moving onto tariffs, things could well have turned out very differently.

Then there are fiscal worries. The US government deficit was 6.7% of GDP (source: ING) over the last year – an almost unprecedented number in peacetime and outside of a recession. The so-called Big Beautiful Bill passed by the House of Representatives will leave the deficit at such levels for the next few years and see US debt to GDP surpass the 106% level it hit in the Second World War by 2028 (source: U.S. GAO).

The US is not yet in a true debt scare, but things have reached the point that some are becoming concerned and exposures are being cut back.

Finally there is the ever-louder background noise of the President venting his anger at the Federal Reserve. Rarely a week goes by without the President taking to social media to castigate the Fed chair for not cutting rates or threatening to fire him.

The real concern here is the threat of a less independent central bank, one which is no longer really targeting low inflation when it sets monetary policy but is instead aiming to make federal debt financing costs manageable. History suggests that such a period of so-called ‘fiscal dominance’ would lead to materially higher inflation and a weaker dollar overall.

This toxic cocktail of factors has sent the dollar tumbling in the first half of 2025.

But it is worth keeping in mind the longer term context.

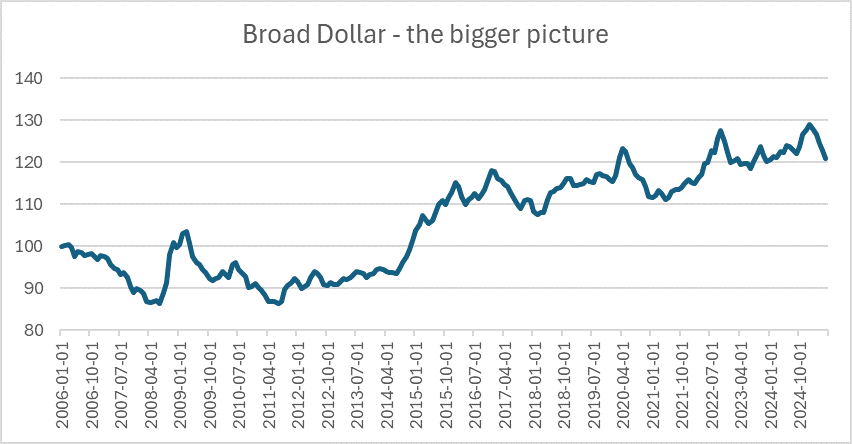

source: SORBUS PARTNERS LLP, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (data as at: 22/07/2025)

For all the handwringing about the last six months the dollar remains roughly where it was in 2022 and materially stronger than a decade ago.

Even a 25% to 30% fall in the value of the dollar from these levels would only take it back to where it was in the early 2010s. Such a move would have major implications for markets and inflation, but it would not represent – as some of the more excitable commentary seems to be suggesting – the unravelling of the wider dollar system or the end of US safe haven status.

The dollar has risen a great deal since the crisis of 2008. The unwinding of some of that strength may prove useful for the wider global economy, even if it causes some pain in the US.

|

What we are watching. Chinese PMI, Aug 1st – The July survey of purchasing managers at Chinese manufacturers will be a crucial datapoint in assessing how the trade war is impacting the all important Chinese manufacturing sector. After months of threats and escalation, the effective trade truce between the United States and China will leave tariffs at a stable, albeit high, level. This may see the sector’s spirits start to revive. Eurozone Retail Sales, Aug 6th – Faster consumption growth will be the key to the Eurozone economy growing at a decent clip this year. Trade tensions with the US have hit the export sectors hard. Real wages have been growing for 18 months but the result has been rising savings levels as households hold back and repair balance sheets rather than spending more. Unless that changes Eurozone growth could weaken in the second half of 2025 from an already low level. UK House prices, Aug 7th – Lower mortgage rates do not seem, so far, to have provided much of a fillip to the British housing market with higher taxes and lower consumer confidence outweighing the impact. |