SORBUS spotlight: The Fed has a tricky choice.

For both the real economy and for financial markets there are few variables as important as the Fed Funds rate. The pricing of stocks and bonds, the direction of the housing market and corporate hiring and investment plans are all ultimately affected, to a greater or lesser degree, by the decisions the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) makes on rates. It is therefore no surprise that there is a veritable industry of Fed watchers constantly second guessing FOMC members, trying to interpret their public utterances for clues as to the direction of policy and with their own readings on the incoming data. Nor is this industry confined to the United States. Given the dollar’s crucial role in global finance, one can find professional Fed watchers in every global financial centre.

What is more surprising, and just a little depressing, is that they are usually wrong.

Over any reasonable time period, financial market expectations of the path of Fed Funds are usually incorrect.

Take as an example the upcoming meeting due to be held on the 1st May. As of the time of writing, market expectations (derived from futures prices and calculated by the CME’s Fed Watch tool) point to a 96% chance of rates being held at their current level of 5.25%-5.5%. In other words, investors are reasonably certain that the Federal Reserve will not be changing its policy rate next month. Given recent higher than expected consumer price inflation numbers, that seems likely to be correct.

But rewind back just three months to late December last year and the expectations looked rather different. On the 22nd of December 2023, just before traders headed off for their Christmas break, the pricing implied that the odds of Fed Funds being 5.25%-5.5% after the March 2024 meeting were just under 12% whilst the odds of a cut to 5-5.25% were more than 75%. Indeed, a rate of 4.75%-5% was seen as more likely than a rate of 5.25%-5.5%. Go back further and the miss becomes larger.

In other words, at the end of the last year financial markets were pricing in at least one – and very possibly two – cuts in interest rates by May. Whereas they now expect none.

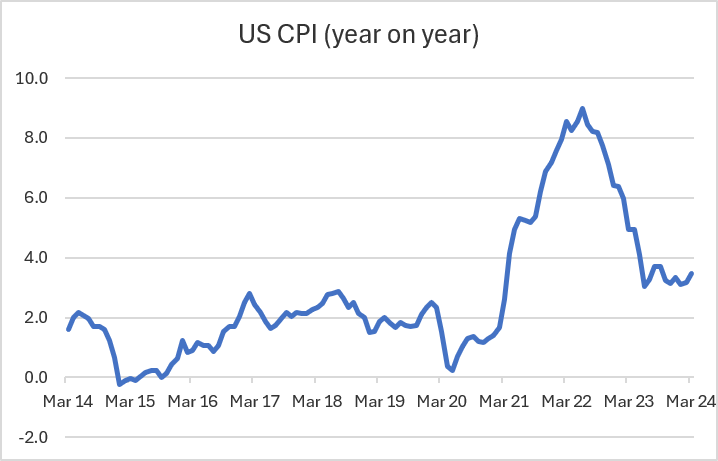

The reason for the shift is the persistence of US inflation. The numbers for March came in hotter than the market expected at 3.5%.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (data as at: 12/04/24)

Whilst inflation is well off its highs and has certainly peaked, the glide path back down to 2% is proving very elusive. As the numbers have stubbornly refused to fall, market expectations of the path of interest rates have begun to move.

The experience of the past few months is a useful reminder that those market expectations of interest rates – even if there is serious money riding on them – should always be taken with a pinch of salt.

There are plenty of reasons why the future-implied path tends to be wrong. Some of it relates to the market often hearing what it wants to hear rather than what was actually said. When the Fed signalled that it was done with hiking last Autumn the market took that to mean that cuts would be following relatively quickly. More generally, close market watchers are keen to point out that the futures pricing is better seen as a snapshot of current sentiment than as something with predictive power for the future.

In general, when rates are low the market prices in hikes and when they are high, it prices in cuts. The belief in mean reversion tends to skew the numbers.

Still, futures traders can at least take solace from the fact that the policymakers actually setting the rates are not much better at predicting what path they will take. For more than a decade the Fed has been publishing the so-called dot plot where FOMC members give their estimates of where rates will be at the end of the current year, in two years’ time and in the longer run. Sadly, there is not much predictive power in these numbers either. As an example, at the end of 2021 the FOMC’s dot plot for the end of 2023 had Fed Funds as likely to be around 1.75%. The hiking cycle that actually followed went well beyond that.

Of course, the dot plot is a prediction not a promise. The Fed, as FOMC members are often keen to emphasize, makes its calls on the basis of the actual incoming data. Higher than expected inflation in 2022 and 2023 led to more hikes than the FOMC had envisaged as being necessary in late 2021.

Another reason to never take the FOMC’s dots at completely face value is that they, in and of themselves, can be thought of as a tool of policy. Expectations of future policy affect financial conditions in the here and now. An expectation that rates will rise in the future, for example, will affect the pricing of long-term loans made today. Sir Mervyn King, when he was Governor of the Bank of England, once referred to this as the Maradona theory of interest rates. As King explained, Maradona scored for Argentina against England in a 1986 World Cup match with an astonishing goal:

“Maradona ran 60 yards from inside his own half beating five players before placing the ball in the English goal. The truly remarkable thing, however, is that Maradona ran virtually in a straight line. How can you beat five players by running in a straight line? The answer is that the English defenders reacted to what they expected Maradona to do. Because they expected Maradona to move either left or right, he was able to go straight on”.

Monetary policy, as King noted, can work in a similar way. Markets react to what they expect a central bank to do as much as what it actually does. The fact that central bankers are aware of this pattern of behaviour of markets matters. It leaves open the possibility of what one might think of as the Jedi mind trick approach to monetary policy.

Take as an example, the Bank of England (BOE). If members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) fear that inflation is likely to overshoot their target they have two tools available to them. The first is the obvious and familiar one; they can move interest rates. That though is a somewhat blunt tool and one which, as Spotlight has often noted, is subject to a long and variable lag before it begins to affect the economy of perhaps 12-24 months.

Another option though is to draw on the Maradona theory. A series of hawkish speeches from MPC members – fretting that inflation is too high and warning that action may need to be taken – can lead to the markets pricing in a higher path of rates as they move to anticipate the path the Bank will follow. That higher implied path of rates changes mortgage pricing in the near term and can have an immediate impact on household spending and consumer confidence. In other words expectations are themselves a potential tool of policy.

Although central banks need to be careful when they consciously try to manage expectations, Maradona after all was a player of legendary talent and most players trying to run 60 yards through five defenders in a straight line would simply get tackled. Some of the BOE, and the Fed’s, attempts to actively manage expectations in recent years have fallen similarly flat.

In reality neither the expectations of financial markets nor the projections of the Fed itself are entirely satisfactory as predictors of the future. The best bet is to keep an eye on the incoming data and keep in mind that the picture is subject to change.

US inflation, as noted, has fallen but remains at a level the Fed is not comfortable with. The US jobs market still seems to be performing well.

source: SORBUS PARTNERS, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) (data as at: 12/04/24)

Wage growth, much like inflation, has cooled considerably but is still running around 1-1.5 percentage points above its pre-pandemic level. Like inflation, the cooling does appear to have slowed or possibly plateaued since the turn of the year.

Just a few months ago many observers confidently expected three to four Fed rate cuts this year. Now that has been scaled back to two at most. There even those who expect no cuts and a handful of voices arguing a hike might be needed.

The changing expectations since January matter, both for the US and globally. In an American context, they represent a tightening in financial conditions – one which may help the Fed to bring down inflation.

Globally though the implications are more problematic. The OECD, a global organisation of mostly rich countries, expects the US to grow by more than 2% in 2024. By contrast it expects sub-1% for the other G7 nations.

Whatever may be happening in the US, the case for rate cuts in other advanced economies is stronger – job markets are weaker, inflation has fallen faster, and growth has materially slowed.

The situation though was easier for the European Central Bank and the Bank of England when it looked like they could be cutting in concert with the US Fed. Cutting ahead of the Fed risks currency depreciation against the US dollar and a possible pick-up in imported inflation. The Fed has a tough call to make – and one that will reverberate outside the US’ borders. It’s a great shame that the whole industry of Fed Watchers cannot provide much guidance.

|

What we are watching this month 17th April, British Inflation: Markets will be watching closely to see if the recent good run of softer British inflation data continues. 25th April, Global House Prices: the Bank for International Settlements tracks 60 global housing markets and makes the data available in a comparable format. The next release is due out at the end of this month and will be a useful spotlight on how property markets have coped with a higher rate environment. 1st May, US Fed: the Fed, as we have seen, is expected to hold rates. More important than the decision itself will be the accompanying tone of the policymakers. |