SORBUS spotlight: pulled in two directions

In an ideal world fiscal and monetary would work to support each other. Sadly the world is often far from ideal but rarely has there been a divergence as sharp as the one currently being experienced in Britain. The government has thrown fiscal caution to the wind and embarked on a tax cutting dash for growth. Meanwhile the Bank of England has increased rates in order to push inflation down and now looks set to go further. This is the macroeconomic equivalent of a driver pressing on the accelerator and the brake at the same time. Something which rarely ends well.

The British economy is afflicted by two problems; a shorter term inflation one and a longer running growth one. The Treasury and the Bank have, unhelpfully, chosen this moment to each focus on a different challenge.

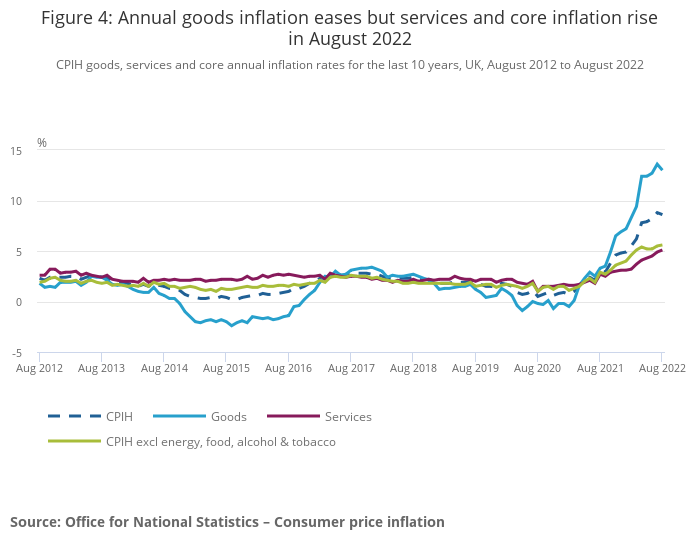

Headline inflation is hovering around the double digit mark, its highest level since the early 1980s. Whilst a proportion of that reflects the surge in global energy prices that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier in the year, that is not the whole story. The jobs market is very tight with more advertised vacancies than unemployed workers. Firms are seeing their wage bills rise at the fastest pace since the late 1990s, adding to their cost bases and pushing up prices. Core inflation, excluding volatile components such as energy and food, is running at around 6%. The price of services, less impacted by global developments and more telling about domestic conditions, rose by more than 5% in the year to August.

The government has moved to cap energy costs for both households and firms which, they believe, will lower the peak of headline inflation by around 5%. But, counterintuitive as it may sound, that lower peak in headline inflation may push the Bank to tighten more rather than less. If households are spending £1,000-2,000 a year less than they would have otherwise on energy they may well spend more on other goods and services, adding to domestic inflationary pressure. Firms which are not crippled by higher energy costs may recruit more, adding to the tightness in the jobs market.

The view of the Monetary Policy Committee, when they raised rates to 2.25%, was that:

While the Guarantee reduces inflation in the near term, it also means that household spending is likely to be less weak than projected in the August Report over the first two years of the forecast period. All else equal, and relative to that forecast, this would add to inflationary pressures in the medium term. (Our emphasis).

The fact that the Bank has been prepared to keep tightening policy even whilst acknowledging that a recession is likely suggests that the Bank has concluded a recession is a price worth paying to return inflation to target. This is in keeping with the Federal Reserve policy.

The government though has put the immediate inflation problem to one side and instead chosen to focus on a longer running one: that of weak growth. In the decade before the financial crisis the British economy was the second fastest growing among the G7 group of countries, second only to the United States. In the decade afterwards it was the second slowest growing, ahead of only Italy.

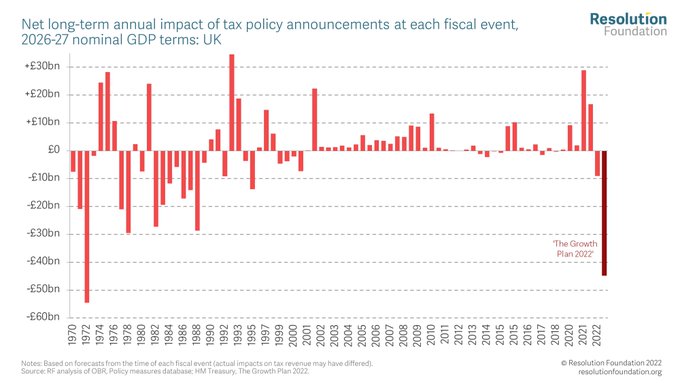

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s new Plan for Growth seeks to reverse this relative decline by leaning heavily on tax cuts. Analysts had been expecting the cancellation of a planned rise in corporation tax and the reversal of a recent increase in national insurance contributions. But the government went much further. A 1p cut in the basic rate of income tax has been brought forward a year and the 45p rate on earnings over £150,000 has been scrapped. Taken together this amounts to tax cuts worth around £45bn a year – the biggest tax cutting budget since 1972.

1972 is a significant year for British economic history. The then Chancellor Anthony Barber aggressively cut taxes as part of a ‘dash for growth’ in the face of already high inflation. The experiment did not go well with the subsequent ‘Barber Boom’ rapidly giving way to the following Barber Bust as the economy overheated, inflation spiked higher and interest rates rose.

The initial market reaction to the Chancellor’s statement will not have gone down well in the Treasury: £sterling fell sharply and the yield on gilts spiked higher.

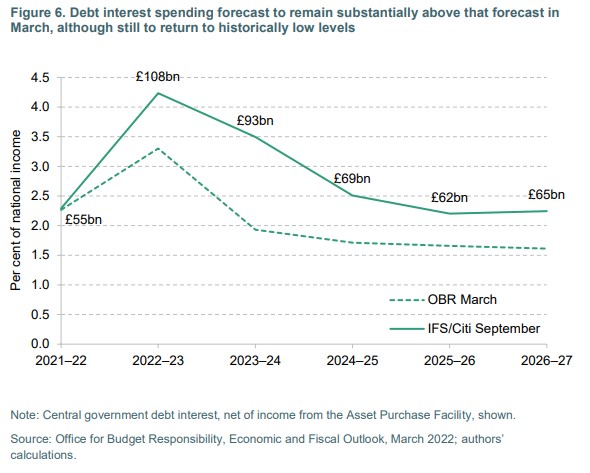

The more excitable commentators have been quick to say that ‘investors are losing faith in Britain’s creditworthiness’. In reality the situation is more nuanced. As the government has pledged to inject more money into the economy, via tax cuts, to speed up growth the markets are assuming, almost certainly correctly, that the Bank of England will move to offset this via higher interest rates. Markets are now pricing in a Bank rate of around 4.5% by next summer. The expectation of tighter monetary policy – rather than fears about default – driving the sell-off in British government debt. But whatever the underlying driver may be, the resulting fiscal arithmetic makes life trickier for the Chancellor.

The financial crisis of 2007-09 and the pandemic of 2020 were both nasty fiscal shocks that pushed Britain’s stock of debt to levels not seen in decades. But, crucially, both were accompanied by falling rather than rising interest rates. The level of debt may have increased but the cost of servicing it fell. This time around not only are debt levels rising but so too is the interest rate attached.

Rising interest rates are not just a problem for the public finances. With two year gilt yields approaching 4%, the typical two year fixed rate mortgage could soon hit 4.5% – the highest level since before 2008.

Rising interest rates will bring pain to firms, households and the government but it is worth remembering that this is exactly what central bank independence is supposed to achieve. The argument for handing over control of monetary policy to technocrats has always been that they can be better trusted than politicians to manage the business cycle. The fear has traditionally been that politicians – with an eye on the next election – will always choose to stimulate growth ahead of the country going to the polls and delay difficult and unpopular decisions. Central bankers, unencumbered by the need to keep voters happy, can focus on the longer term picture. Even if that means delivering short term pain. Whilst the Bank has been independent since 1997, this theory has never really been put to the test in Britain before. Right now though with inflation uncomfortably high and the government choosing to stimulate the economy regardless, the Bank will find itself playing the role of ‘bad cop’ for the first time. Many believe that the BoE has either misjudged the scale of the inflationary pressures or has been too reluctant to play the bad cop; either way the UK has lagged and continues to lag the US response to inflation. Last week was a case in point, the US raised interest by another 0.75%, the UK by another 0.5%. It is just too timid and this is one of the main reasons the US$ has risen so steeply against £ sterling.

The end result of much looser fiscal policy coupled with tighter monetary policy will probably be a rate of growth not that different from what was expected anyway. Lower taxes may encourage some more investment from firms but higher rates will deter others. Households may spend a touch more given their higher take home pay packets but higher mortgage costs will depress consumer desires. The real problem with hitting the brake and the accelerator at the same time is that, in the end, you don’t go anywhere.

|

WHAT TO WATCH FOR IN THE NEXT MONTH CHINA PMI, 30th September: If it was not for a slowdown in the US and Europe, radical changes in British policy and soaring energy prices then the serious slowdown in China’s economy would be dominating global macro commentary. Next month Spotlight will be turning to what is happening in the world’s second largest economy. On the 30th September the private sector survey of purchasing managers should give a timely indication of just how bad things are getting. US MANUFACTURING NUMBERS, 3rd October: The US economy has shrunk for the last two quarters. In both cases consumer spending remained robust and the decline appeared to be more about inventory adjustments rather than final demand. But with the Fed aggressively hiking and mortgage rates at 25 year highs a ‘real’ recession is becoming more likely. Manufacturing is a bellwether sector for the US and worth watching. UK JOBS MARKET, 11th October: Quite how far the Bank of England hikes in the months ahead will be mostly determined by what is happening in the jobs market. As long as it remains tight and wage growth fast then the hiking cycle will continue. The monthly jobs market update is now the most important UK macro data.

|