The Dragon roars

“When you combine ignorance with leverage, you get some pretty interesting results.”

Warren Buffett

There is considerable academic research showing that stock markets are forward indicators of economic growth. If a stock market rises steeply then all things being equal it indicates that positive economic news is around the corner.

On the face of it this makes sense. Share prices should reflect future corporate earnings growth. If shares are rising it implies that growth will be higher than expected. There is also a reflexive element to this. When shares rise it creates a wealth effect – people feel better off and raise spending which in aggregate increases corporate sales and revenues.

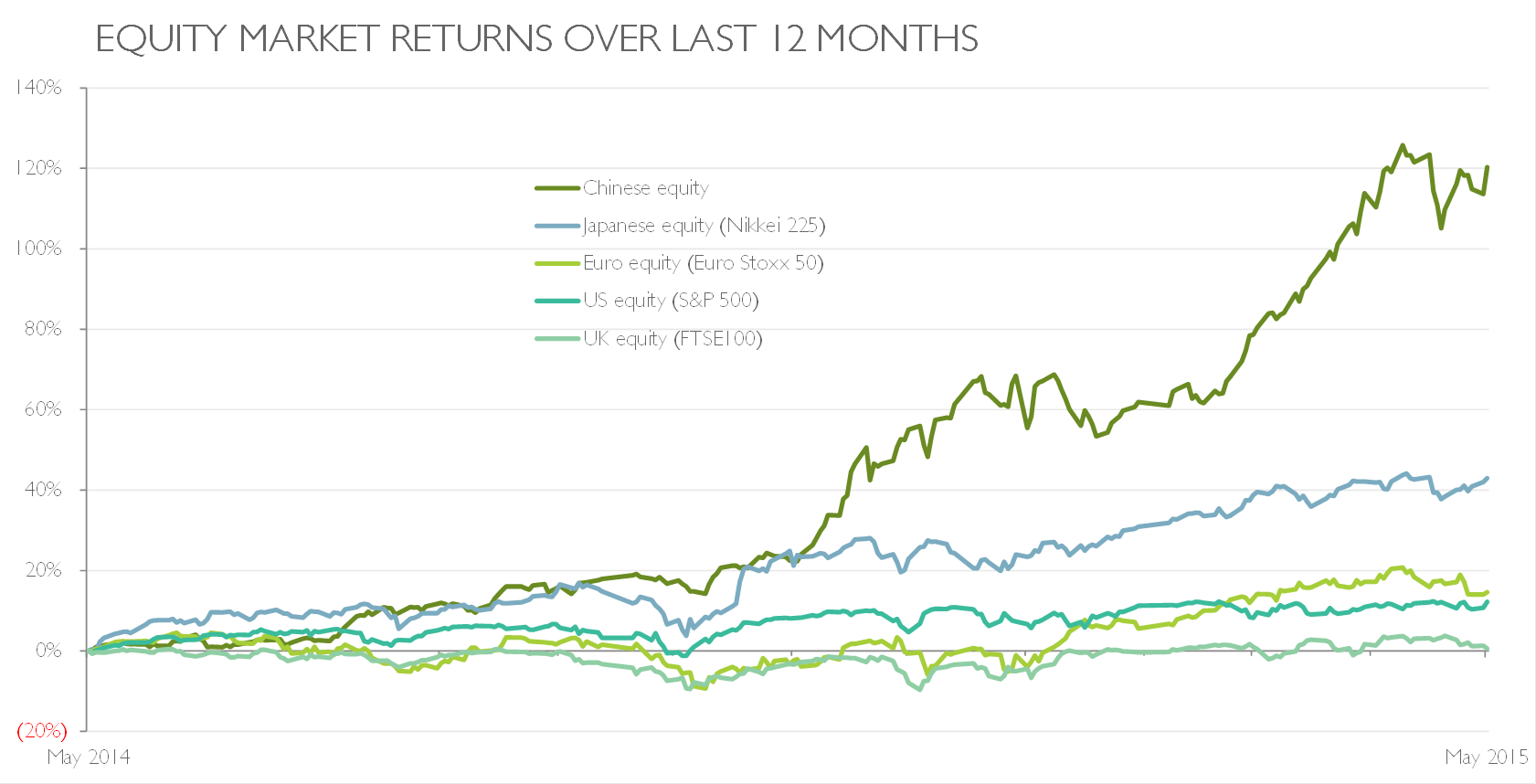

Chinese stock markets have been catching the eye. From a performance perspective it is obvious why. It has been by far the best performing geography (in investing terms) over the last year despite declining growth rates and significant structural questions over the sustainability of its economic growth.

The two questions we will explore are; why this surge has happened and whether it has a meaning?

To place some context around the second question, does this stock market rise in China follow the same predictive pattern and are we looking at faster growth than expected (which would have a major impact on global growth)? Or is it a mirage?

This is an important question. China is the world’s second largest economy and its economy is now 15% of global output (compared to 6% twenty years ago). It has accounted for over half of global GDP growth in the last decade. The expectation among analysts is that Chinese growth is both lower than the (notoriously unreliable) official estimates and slowing. If the rise in the Chinese stock market suggests that there may be upwards revisions of expectations, this would be significant news.

Why has the surge happened?

We would classify the rise as having three main elements: it is a dangerous investment bubble (1) fuelled by speculative capital from retail customers (2) abetted by weak regulation and market oversight (3).

- Investment bubble

The Chinese market has more than doubled over the last year and the rally is the biggest (by value) in history. This is not being driven by improvements in economic fundamentals or corporate profitability, it is being driven by liquidity. This is a clear sign of a bubble.

The average PE (price to earnings ratio) for stocks listed in Shenzen is 64x. Smallcaps average 84x. ChiNext (a tech heavy index similar to NASDASQ) is on 140x. The long term average for western stock markets is between 13x and 15x: the valuations of Chinese stocks are reminiscent of the valuations towards the peak of the dotcom boom. The language being used to describe the business growth opportunities closely echo the language used to describe the potential of the internet in the late 1990’s.

- Speculative capital from banking and retail customers

In August 2014 the Chinese banking authorities, concerned about property speculation and the aggregate size of the shadow banking industry, instigated a change in regulatory policy that restricted property lending but loosened stock market activity by easing liquidity conditions. It also introduced Mutual Market Access (MMA) which allowed investors in Shanghai and Hong Kong the opportunity to invest in each other’s stock exchanges. During a single week in August 2014, Xinhua News Agency put out eight features espousing the wisdom and patriotism of owning equities. This surge in speculation was intentional.

Banks that used to lend to small businesses and for property speculation are now transferring their capital into stock market investments. The consequence of the legislation trying to curtail the shadow banking sector is that they are turning banks into hedge funds.

The man in the street in downtown Shanghai is never slow to spot the opportunity for speculation. As the stock market rose he opened a trading account so that he could participate. Many opened more than one now that the rules had been relaxed so that an individual can open up to twenty. In March retail investors opened more than 4.8m new trading accounts. In the first two days of April a further 1m accounts opened. These are accounts opened at Chinese brokerages and mostly funded by margin (where the brokerage lends clients a proportion of the money invested and charges interest).

The timing of the opening up of China’s equity markets to outside investors is also not coincidental. The excessive indebtedness of many Chinese banks and the rise in non-performing loans has encouraged the notion that a surge of foreign capital recapitalising Chinese companies at implausible valuations is beneficial. It clearly is from the standpoint of the companies – they get to raise substantial capital at very little cost.

Investors, at these valuations, are likely to lose substantial sums.

By mid April the daily volumes being traded on the stock exchange was double that of London, Frankfurt and Paris combined. The companies listed on the Shenzen stock market are now more valuable than those listed on the UK stock exchange and are catching up fast with the Japanese stock market (the second largest in the world). The Shanghai stock market (a separate stock exchange) is now valued at $10trillion. It has also doubled and effectively “added a Japan” (Japanese stock market value is $4.8trillion) over the last year.

The stock exchange itself (the equivalent to the London Stock Exchange) is now valued at $47bn making it substantially the most valuable in the world. The value of the brokerages has also risen to reflect this surge in trading: Citic Securities, China’s biggest stock-broker, has more than doubled in value over the last six months. Haitong shares have quadrupled, which has allowed it to recently raise a further $4.25bn in a share placing, which is used to provide further credit to existing and new clients.

The circularity of this process is obvious.

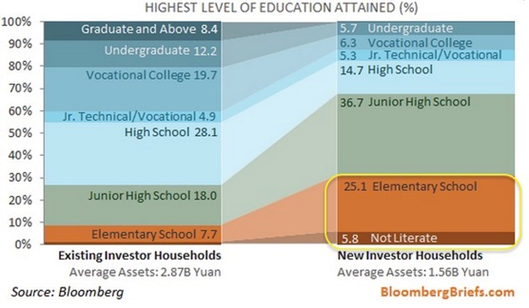

Some interesting analysis has been undertaken on who is opening the accounts: more than two thirds have been opened up by people who left school no later than the age of 15.

Does this sound like it will end well?

- Weak regulation and market oversight

We will touch on these elements but two companies exemplify the trend, though they are admittedly at the extreme end of the spectrum and only generally representative.

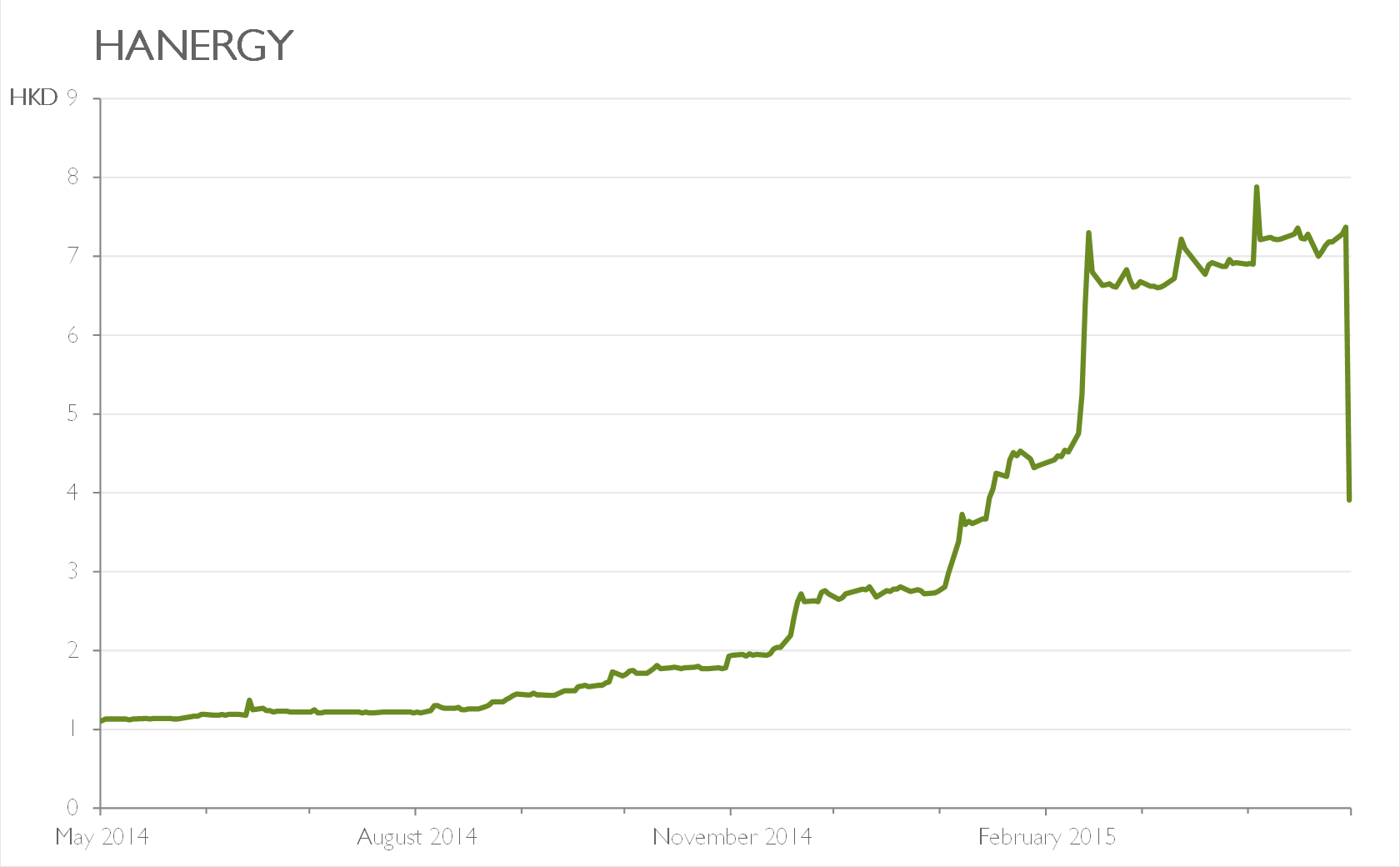

Hanergy Thin Film Power is a Chinese solar equipment supplier. Over the last year the shares have risen from HK$1.12 to HK$7.40. As of late May it was valued at $35bn and had made Li Hejun, the group’s founder, the richest man in China. He was being compared to Steve Jobs. Its success had gone largely unheralded outside China but it gained instant notoriety after a Financial Times investigation in March. The journalists revealed a two year pattern of what looked like price manipulation of its shares. Between 3.50pm and 4.00pm (when the stock exchange closed) Hanergy’s price consistently surged. This late surge was entirely responsible for the, otherwise baffling, rampaging share price. If you started each day over this period buying Hanergy shares first thing in the morning and then selling them before the surge at 3.50pm you would have actually lost money.

Hanergy at this price was valued at five times more than its largest US based competitor and it was also worth more than the rest of the Chinese solar sector combined.

Further investigations revealed that almost all of its revenues are generated by its parent company.

This incriminating trading data, combined with limited corporate disclosure and a number of related party transactions, would have led to an immediate suspension had the stock been listed on a developed world stock exchange.

Hanergy shares not only continued trading but its share price was unaffected…until the traders turned against it some weeks later. The share price reflects a stock market and capital markets infrastructure that is neither undertaking sufficient due diligence nor is pricing risk effectively.

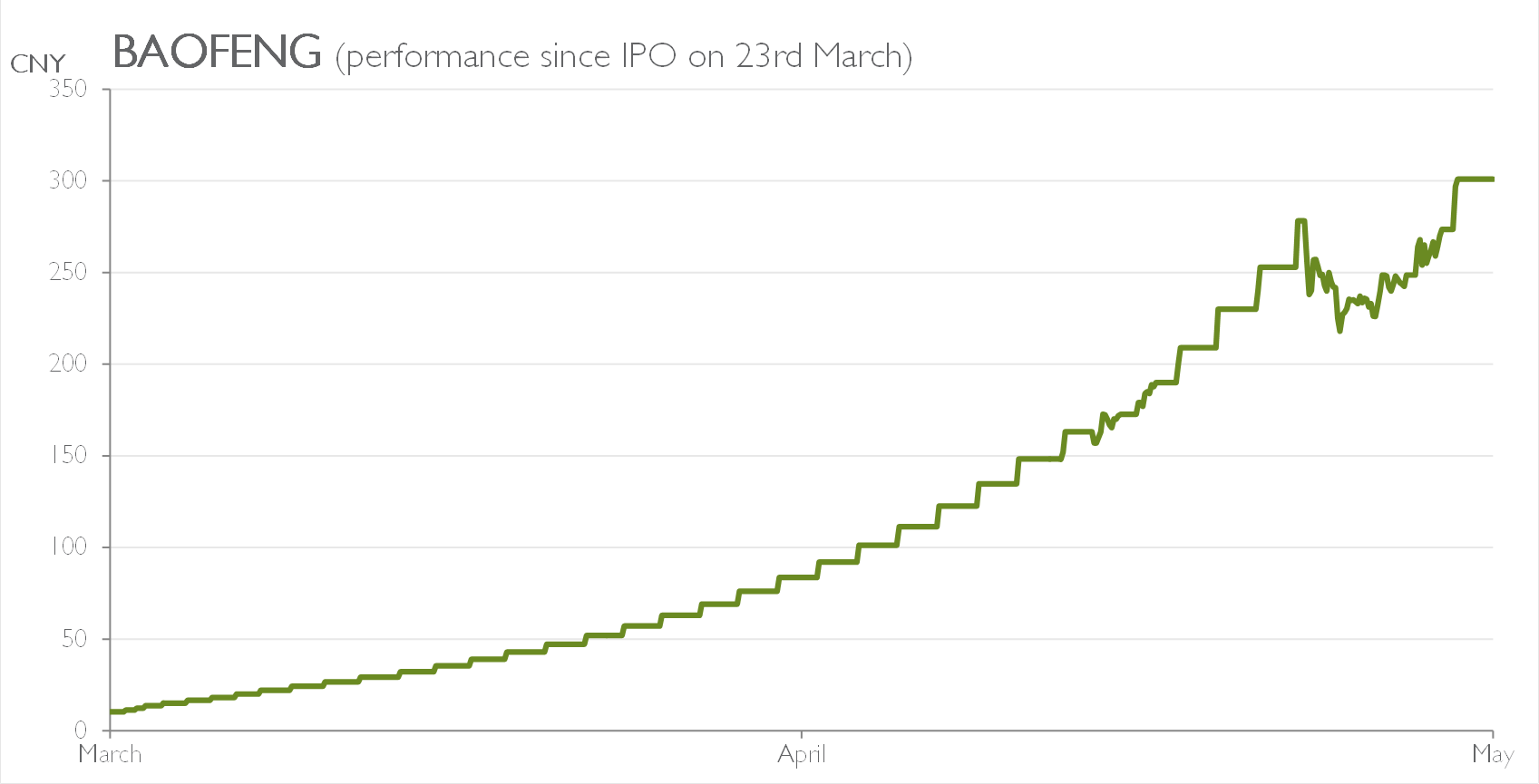

Another company that caught the eye was Baofeng Technology a hitherto unremarkable online video company. It rose by 44% when it floated and then rose by the maximum amount before trading ceases (10% a day) for the next 30 days until it was worth over $2bn.

The inescapable conclusion is that the shares are being bought by people who are not paying attention and are subscribing to the “greater fool” theory.

The buyers appear to neither notice nor care that the valuation of the stock they are buying is absurd. Their only consideration is that they think it will go up and that they will be able to sell (at a profit) to a “greater fool” than them. They may well be right, at least in the short term.

While Hanergy is a clear example of suspicious, possibly fraudulent, activity, the Baofeng rise represents merely a speculative trading story of ever increasing absurdity. We will cover the subject of fraud and investing in emerging markets in a subsequent update.

Conclusion

This is a liquidity driven bubble and neither reflects nor predicts the economic fundamentals of China. It can (mostly) be ignored. The economy is not going to catch up on the valuations and investors who buy such assets at these prices will inevitably lose a substantial proportion of their capital.

That it can be identified as a bubble, however, is not a short term prediction of a correction. Bubbles, even when widely identified, grow bigger and higher than imaginable at times before finally popping.

There has been increased volatility (rather than just one way upwards trading). This is worth looking out for; as is the occasional event when the market turns on a stock (as can be seen with Hanergy). The growth in accounts and the role of margin is also another indicator that additional further sources of liquidity to keep supporting prices and price rises may be wearing thin.

Bubbles pop not because of an outbreak of collective wisdom but because liquidity dries up. When this happens prices stop rising, and start falling. When prices continue falling the man who has opened 20 trading accounts funded with debt sees his paper profits evaporating rapidly. Another bad day or two and he is required to supply additional credit to support his investment positions (a margin call).

He has no additional funds, as he never had the capital in the first place. Shares are sold irrespective of the price and we have the conditions to create a market crash.

As the speculative surge was facilitated and indeed encouraged by the Chinese government it will be interesting to consider the likely actions under such a scenario. That a monster has been unleashed may well be dawning upon the governing elite in Beijing however an attempt to intervene to quell sharp market declines, and the ensuing financial pain, is likely. Such intervention may provide temporary respite but the speculative nature of the bubble and the sheer quantum’s involved suggest that the Chinese government has overestimated its capacity to control stock markets.

It is easy for rational UK investors to avoid direct exposures into the Chinese stock market and companies like this but many will be unwittingly investing via funds or ETF’s in their model portfolios.

The MSCI Emerging markets index is 25% weighted to China. So if you own an emerging market fund the chances are you have 25% of it invested in Chinese equities. If you own a generic private bank portfolio then you will hold exposure to this asset class all the way down and you should consider appropriate steps to avoid such potential losses.