Phones4U evaporates

Private Equity – not the mobile operators – killed Phones4U”

Jonathan Ford—Financial Times

“This is an unprecedentedly ruthless and probably collusionary event that has caused the demise of a great business”

John Caudwell

It is rare that an established and profitable business goes into administration. The Phones4U story is significant, not just locally, but because of what it reveals about management, finance and investing.

BC Partners (a private equity firm) bought Phones4U in March 2011 for approximately £700m of which £200m was equity. Most of the debt was provided by the issue of £430m of senior bonds. This was the second private equity group to own Phones4U, in addition to two internal recapitalisations, since it was sold by John Caudwell.

In September 2013 BC Partners issued £205m of PIK (Payment in kind) notes which allowed them to pay a £225m dividend to the equity holders. One year later the company collapsed into administration on the news that its remaining two network suppliers (Vodafone and EE) would not extend their commercial ties with the distributor.

The press over the subsequent days was replete with journalists and Phones4U’s network suppliers blaming the private equity firm who in turn (with additional vocal support from founder John Caudwell) blamed the networks.

Both sets of parties and arguments are mostly wrong: the demise of Phones4U is principally the fault of the changing distribution strategies of mobile phone networks leaving it with an obsolete business model. Cancer victims often die of a heart attack but the cause of death is rightly attributed to the cancer. Business models have varying lifespans. It is hard to see what might intervene in the next 100 years that would end the requirement for toiletries or drugs for example and it is hard to envisage demand ending for bakers, lawyers, accountants, hairdressers and plumbers (amongst many services).

However, technology has an increasingly rapid adoption and redundancy cycle and the internet has accelerated the obsolescence of retail formats. It seems that a high street point of sale for mobile phones and their network contracts has residual value as currently only 10% of phones/network are bought directly online. While there is complexity in terms of the purchase decision a served environment (shop and sales staff) has a value, but for how long is an interesting question: 10 years? The demise of Phones4U demonstrates that networks no longer require an independent retailer in order to distribute their product – they can do it themselves – and so naturally will cease to pay them for doing so. This pressure had been accumulating for some time and the decision of Vodafone to cease supplying Phones4U revealed the binary fragility of its model: profitable or dead.

The balance sheet structure imposed by the private equity firm and the competitive actions of the network suppliers played a role in the timing of the collapse but the fate of independent retailers had looked increasingly bleak for some time.

Phones4U’s demise well signalled

The three largest mobile phone network suppliers (Vodafone, O2 and EE) control approximately 80% of the UK market. Having previously relied on independent distributors to sell their products they had all started to build out their own branded high street stores. As such Phones4U was gradually moving from being a partner to being a competitor. Phones4U had often trumpeted its ability to attract a young demographic but it appears the networks clearly did not believe that Phones4U was adding sufficient value.

The networks had a few strategic options as regards Phones4U but taking advantage of the opportunity to exploit Phones4U’s stretched balance sheet was probably too tempting to resist. Why build your own retail presence or even buy Phones4U (preliminary talks were held between Phones4U and Vodafone/EE earlier this year) when you can cherry pick the stores you want from its administrator for free?

Fairly obvious warning signs for the future were when O2 stopped supplying Phones4U in January followed by Dixons and Carphone Warehouse merging (meaning that the Dixons distribution outlet for Phones4U would inevitably be ended). Phones4U were left with two suppliers who had essentially no interest in the continued existence of the company. When Vodafone announced that it would not extend its supply contract the writing was on the wall and EE subsequently announcing it would do the same was then inevitable.

So would Vodafone have pulled the plug on the Phones4U distribution deal if it had no debt? In the short term the answer is that it is possible but on balance unlikely. Vodafone would be wary of taking the hit to distribution while its retail presence is developing, but with a growing retail chain directly competing with Phones4U it is hard not to see the demise of the partnership within a year or two. The high level of debt did not cause the demise of Phones4U but it almost certainly accelerated it. It also eliminated any prospect of the management team developing or implementing an alternative strategy though again it is hard to see what strategic options were available – they could possibly have acted as a channel to market for new entrants and subscale participants but this hardly looks an attractive proposition. We would imagine that Dixons/Carphone Warehouse will be thinking hard about their options as the same forces that undermined Phones4U apply to its network distribution business.

Distribution businesses seldom have attractive economics – they tend to have thin margins and can be capital intensive. The fact that Phones4U was making 10% operating margins may well have encouraged its suppliers to consider whether they were paying away too much of the value-chain to their distributor. That 60% of these profits were going to pay an ever increasing amount of debt may also have clarified its partner’s minds over the long term attractiveness or even viability of Phones4U.

We would suggest that the balance sheet stress merely provided Vodafone and EE with the opportunity to secure the distribution they desired at low cost. Were Vodafone and EE ruthless? No, they were presented with a gift-wrapped opportunity to gain a competitive advantage by the reckless behaviour of BC Partners. Criticism of Vodafone and EE is misplaced.

Unintentionally comic moments in the mudslinging that followed the announcement include a comment from Stefano Quadrio Curzio, the BC Partner in charge of the company “Vodafone has acted in exactly the opposite way to what they had consistently indicated to the management of Phones 4U over more than six months. Their behaviour appears to have been designed to inflict the maximum damage to their partner of 15 years, giving Phones 4U no time to develop commercial alternatives”. With an apparent lack of irony this is a private equity firm complaining that a competitor has acted competitively. He also fails to acknowledge that it was BC Partners that handed the strategic advantage to its competitors by financially hobbling Phone4U.

Further irony deficits are evident in John Caudwell complaining about the fate that befell his “great business”. Well, definitions may vary, but we would not classify any business as “great” that is forced into administration by the disappearance of its only two suppliers.

So who bought the debt!?

As it happens both the private equity firm and the network suppliers doth protest too much, methinks. BC Partners made a profit on its investment in Phones4U and the network suppliers get to largely complete their high street portfolio at low cost and take out a competitor. The losers here are the head office staff who will be made redundant and the holders of the Phones4U debt.

The former deserve our sympathy but the latter deserve nothing but scorn. Excessive supplier concentration is a major latent risk for any organisation and amplifies risks significantly. These risks were high and rising at Phones4U. Not only was there increasing concentration between suppliers (EE is an amalgam of the UK Orange and T-Mobile networks) but a maturing industry was increasingly comfortable managing its own shops. Vodafone shops were not appearing on high streets up and down the UK by stealth. The developing strategic threat and inherent vulnerability of Phones4U has long been obvious. It appears to us to be a legitimate question to ask why those who held the £430m of senior debt and especially those who bought the £205m of junk PIK notes did not observe such risks?

For clarity PIK notes are high risk often unsecured debt that can have a variety of differing features but most commonly have a toggle that allows the issuer to decide whether the holders receive any interest or whether it is rolled up. PIK notes are best known for being the type of debt financing used by the Glazer family in their acquisition of Manchester United Football Club – incidentally the football club has to date spent over £700m servicing this debt.

Another unpleasant feature is that usually PIK notes are issued by companies that already have bonds outstanding (as is the case with Phones4U) which has a series of consequences. The senior bonds previously issued would typically have covenants restricting the operating company’s capacity to pay dividends. As such the PIK notes are often issued out of holding companies that are not affected by these restrictions. But the holding company will not have any cashflows (as dividends payable to it from the operating company are restricted) so the only way in practise that these PIK notes gets repaid is by injecting equity capital, which in this instance is simply not going to happen. Because of these limitations PIK notes are considered to have very high refinancing risks (the ability to roll over the debt into a new loan at maturity) and are usually only issued by companies that are confident of high growth. It was an inappropriate form of debt structure for Phones4U.

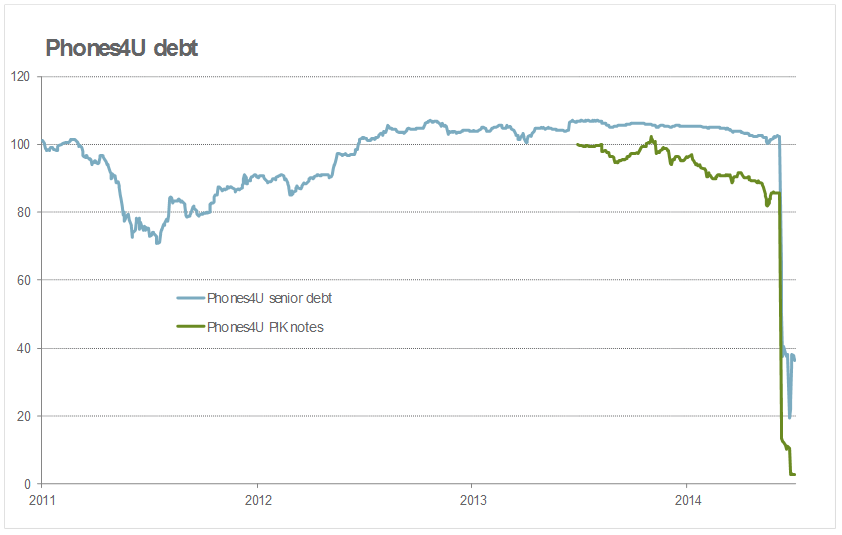

The price of Phones4U debt has been remarkably stable despite the escalation of bad news as a look at the graph below will attest. You will note that the price of the senior notes is untouched by the issuance of £205m of PIK notes and a £225m dividend recap, the decision by 02 to cease supplying it, and the Carphone/Dixons merger all of which clearly signalled a worsening financial, competitive and strategic position.

This is genuinely unusual. The debt may have been thinly traded and listed in Dublin but we would have expected the market participants to be pricing the debt instruments efficiently but it appears that this was not the case.

This also raises the secondary question of who were the holders of this debt and why do they appear to have been so negligent?

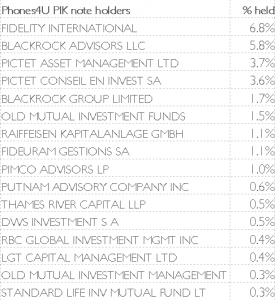

The list of holders of the PIK notes has not been disclosed in the press so for interest’s sake we will publish them here. It may seem surprising, given the low quality of the Phones4U paper, but the holders are not hedge funds or high-risk investment funds, they are the global grandees of debt investing.

Actually this was quite predictable and is a direct consequence of the risk management techniques employed. Risk, as far as these fund managers is concerned, is not about whether the bond goes bust or not. They do not really care about that. What they care about is looking better than their peer group because if they “outperform” then more money will be given to them to manage and the inverse will happen should they “underperform”. The risk from their perspective is not about whether they make any money for their clients (or avoid losing it) it is the extent to which their investments differ from the benchmark. If they stay close to the benchmark they cannot underperform much and as such are unlikely to see significant fund outflows. If they differ significantly from the benchmark they increase their active management risk. This is the risk that they care about and the major fixed interest asset managers have teams of analysts and compliance officers ensuring that this risk is managed down – that the fund managers do not stray far from their benchmarks.

The consequence of this risk management is that fund managers are effectively required by their internal controls to buy pretty much every major issuance irrespective of quality or price because the issue forms part of the benchmark and not owning it would be too high risk.

This is clearly a perverse outcome from what is described as “risk management” but it is pervasive across much equity and debt investing. Every time an investor agrees to measure their investment manager with reference to any benchmark (other than an absolute return benchmark) they are setting in place a chain of unintended consequences that results in massive debt investors such as Fidelity, BlackRock and Pimco mechanistically investing in junk.

In February this year we wrote that when considering an IPO you should be “uncomfortable buying anything from a private equity owner”. The Phones4U collapse provides a sad endorsement of this caution, and reinforces that this applies to debt as well as equity, though ultimately private equity was not the villain of this tale.

NOTE: In terms of disclosure we should state that SORBUS only uses absolute return benchmarks with our clients and none of our preferred fixed income houses use benchmarks (or invested in either the Phones4U senior debt or PIK notes)